Revisiting the preservation of Tranquility Base and other historic sites on the Moonby Michael J. Listner

|

| Any claim of authority over the lunar surface to fulfill the intent of the National Historic Landmark Act would raise the ire of the other signatories of the Outer Space Treaty. |

Under this regulation, properties that would be designated National Historic Landmarks are done so only if they are considered significant. This determinations is made by professionals, including historians, architectural historians, archeologists, and anthropologists familiar with the broad range of the nation’s resources and historical themes. Criteria applied by these specialists to potential landmarks establish a qualitative framework in which a comparative professional analysis of national significance can occur. The Secretary of the Interior makes the final decision on whether a property possesses national significance, and that decision is based on documentation, including the comments and recommendations of the public who participate in the designation process.

Properties designated under the National Historic Landmark Program are administered by the Department of the Interior and consist of real property that is either under the direct control or within the jurisdiction or sovereignty of the United States government. This requirement would disqualify Tranquility Base because the artifacts on the lunar surface are space objects, which the United States retains jurisdiction to under Article VIII of the Outer Space Treaty, and are not affixed to the lunar surface nor are they real property. Therefore, even though the United States retains sovereignty and control of the artifacts left on the lunar surface that sovereignty doesn’t extend to the physical lunar territory that encompasses Tranquility Base.

In order for the site at Tranquility Base to be recognized as a National Historic Landmark under 36 CFR § 65.4, the United States would have to claim and exercise jurisdiction and sovereignty over the physical lunar surface that encompasses Tranquility Base. This would violate Article II of the Outer Space Treaty whereby outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means; that means that no nation can claim territory on the Moon or other celestial bodies as its national territory. Any claim of authority over the lunar surface to fulfill the intent of the National Historic Landmark Act would raise the ire of the other signatories of the Outer Space Treaty and result in significant geopolitical political fallout.

The American Antiquities Act of 1906

Another approach discussed in the SPACE.com article for preserving Tranquility Base is the use of the American Antiquities Act of 1906. The Antiquities Act, which is codified in 16 USC 431, is directed at the preservation and protection of any historic or prehistoric ruin or monument, or any object of antiquity, situated on lands owned or controlled by the US government. It also serves to levy fines for unauthorized excavation or destruction of these sites. Most importantly for the issue of applicability to the preservation of Tranquility Base, the Antiquities Act grants the President of the United States the power to “declare by public proclamation historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated upon the lands owned or controlled by the Government of the United States to be national monuments.” Moreover, when a historically significant object is affixed to private real property, the President is allowed to condemn the real property if it is necessary to properly preserve and protect the object.

However, because the lunar surface is not the property of the United States government, the use of the Antiquities Act of 1906 to preserve and protect Tranquility Base would fail for the same reason that the National Historic Landmark Act would: use of either would require a sovereign claim of ownership over the lunar territory encompassing Tranquility Base, which would be in direct violation of US obligations under Article II of the Outer Space Treaty. While the Antiquity Act of 1906 grants the President authority to condemn private property upon which a historically significant artifact is located, it does not grant him the authority to claim sovereign-less territory. Furthermore, the power to claim sovereign territory was neither conceived nor authorized by Congress when the Antiquities Act was passed, so not only would a declaration over the site at Tranquility Base be illegal under international law, it would also be outside the enumerated powers granted to the Executive Branch either by Congress or the Constitution. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that a declaration by the President may not only incite an international incident, but could raise the ire of Congress as well, and likely would not stand up to judicial scrutiny. Consequently, it is unlikely that the President could or would employ the Antiquities Act of 1906 as a means of legally preserving Tranquility Base.

Preservation of sites within areas designated as res communis

Another method of preserving Tranquility Base mentioned in the article is the idea of exceptions for preservation within areas designated as res communis or “the common heritage of all mankind.” The principle of res communis is mentioned not only in the Law of the Sea Treaty but also as the underlying principle of the Moon Treaty. The article suggests preservation of sites within areas on the surface of the Earth that are considered res communis, which has been successfully applied to preserve camp sites in the sovereign-less regions of Antarctica, could be employed to preserve Tranquility Base.

| Existing law and international mechanisms are inadequate to protect historically significant extraterrestrial sites such as Tranquility Base. |

The impediment of this line of reasoning resides with the principle of res communis in regard to the Moon itself. Specifically, for the United States to employ the precedent of preserving significant sites upon the lunar service in spite of res communis would require that the United States recognize internationally that the Moon represents territory falling under that principle. However, the one significant legal document declaring that the Moon is res communis is the Moon Treaty of 1979, which the United States neither a party to nor recognizes as binding international law. Therein lies the dilemma for the United States.

Article 11(1) of the Moon Treaty states in part that “[t]he moon and its natural resources are the common heritage of mankind...”, i.e. res communis. Therefore, an attempt by the United States to preserve Tranquility Base by citing the precedent of preserving sites within territory declared as res communis could be construed as an acceptance of the principle of res communis within the context of the Moon Treaty, and perhaps the customary acceptance of the Moon Treaty as a whole. This would run counter to current US policy in regards to international space law and could encumber the United States within another space law treaty without the opportunity to amend or otherwise renegotiate it. Moreover, even if another nation offered to make such a designation of Tranquility Base, the potential legal pitfall would remain the same if the United States agreed to allow the space objects under its jurisdiction contained in the site to be included within that designation. Given this potential legal binding, it is doubtful that either the Executive Branch or Congress would be willing to take this approach to preserve Tranquility Base.

The Sunken Military Craft Act

Existing law and international mechanisms are inadequate to protect historically significant extraterrestrial sites such as Tranquility Base. However, a domestic evolution in law regarding the treatment of sunken warships and military aircraft might form a basis or provide guidance for future laws to preserve these types of sites. The key lies in the customary maritime law principle that recognizes an exception to the right of salvage for the wrecks of federal warships. Specifically, customary international law recognizes that federal warships submerged in international waters remain the property of their countries of origin unless they are expressly abandoned. This precept of maritime law is generally recognized and has been upheld by courts, including those of the United States.3 It is noteworthy that this principle is similar to the precept of ownership of space objects outlined in Article VIII of the Outer Space Treaty.

Building upon this principle of international law, the United States has taken affirmative steps to ensure that the wrecks of its sunken warships and aircraft are not disturbed by other governments or private individuals under its jurisdiction. In a step to codify the desire to protect the wrecks of its sunken warships and military aircraft and to provide uniformity of law across the federal circuit courts, Congress enacted The Sunken Military Craft Act, which was signed by President George W. Bush on October 28, 2004, as part of the 2005 National Defense Authorization Act.4

The Sunken Military Craft Act is designed to provide a clear statement of United States policy regarding ownership of sunken military ships and aircraft and to induce other nations to respect US ownership and produce parallel expressions of sovereign intent. The major maritime powers, including Great Britain, France, Germany, Japan, Russia, and Spain, have articulated positions similar to, or acted in conformity to, the US policy position. The Sunken Military Craft Act provides among other things for:

- Protection of sunken US military ship and aircraft wherever located.

- Protection for the graves of lost military personnel.

- Protection of sensitive archaeological artifacts and historical information

- Codifies existing case law, which supports federal ownership of sunken US military ship and aircraft wrecks.

- Provides a mechanism for permitting and civil enforcement to prevent unauthorized disturbance.

- Provides for archaeological research permits and civil enforcement measures, including substantial penalties, to prevent unauthorized disturbance.5

One interesting aspect of The Sunken Military Craft Act is that it encourages diplomatic efforts for multilateral and bilateral agreements with foreign countries for the protection of sunken military craft. While codifying the protection of sunken military craft in international waters, The Sunken Military Craft Act also seeks to find agreement with other nations to support and enhance the protection affirmed within. This makes the law’s efforts proactive to protect sunken craft through its jurisdiction over its domestic citizens while seeking accord among a broader group of nations.

| A law like The Space Objects Preservation Act could draw upon past and current preservation laws to provide a foundation to identify and preserve historically significant extraterrestrial sites. |

Considering the analogous ownership nature of sunken military craft and the continued ownership of space objects under Article VIII of the Outer Space Treaty, the Sunken Military Craft Act provides a starting point to create a domestic law designed not only to protect the artifacts within Tranquility Base but also the entire site.

The Space Objects Preservation Act

To address the issue of preservation of historically significant extraterrestrial sites like Tranquility Base, the jurisprudence of space law must evolve with the creation a new domestic law to recognize the historical significance sites like Tranquility Base and the need to preserve them for future generations. The new law would also have to address the intricacies and limitations of international space law as well as have the flexibility to interact internationally to form a consensus about the need to preserve these space objects and the sites they are located within.

The advent of telepresence, as well as looming future commercial and government human activity, means that historically significant space objects and sites, including the signs of human activity left in the lunar regolith such as that found at Tranquility Base, could potentially threatened in the near future. A law like The Space Objects Preservation Act could draw upon past and current preservation laws, such as the National Historic Landmark Act and The Sunken Military Act, to provide a foundation to identify and preserve historically significant extraterrestrial sites and to grant them legal protection beyond what is provided by current international space law.

To that end, the Space Objects Preservation Act might have some of the following characteristics:

- Reassert the continued ownership by the United States of space objects, including those upon the surface of extraterrestrial bodies, under Article VIII of the Outer Space Treaty;

- Provide a review process whereby historically significant space objects and/or sites are identified for protection;

- Provide for a register of historically significant space objects/sites to be administered by the NASA Administrator;

- Provide for the protection of space objects from interference either by direct human contact or through telepresence by restricting access to those space objects or sites;

- Provide for a permitting process for authorized examination of those space objects and/or sites by qualified experts;

- Provide for civil enforcement and penalties for any citizen under the jurisdiction of the United States who either interferes with, damages, or destroys a historically significant space object or site without permission.

Most significantly, The Space Objects Preservation Act would include an authorization similar to that found in The Sunken Military Craft Act, which would encourage the NASA Administrator and the Secretary of State to interact with other nations to enter into either bilateral or multilateral transparency and confidence-building measures directed towards the preservation of historically significant space objects and sites. The purpose of this interaction would be intended to not only encourage other spacefaring nations to provide reciprocal measures to protect their own historically significant space objects and sites, but also to create a norm of international law recognizing that historically significant space objects and the tracts of extraterrestrial real property they reside on can be preserved and protected by their nations of origins in a manner that does not equate to a claim of sovereignty.

Conclusion

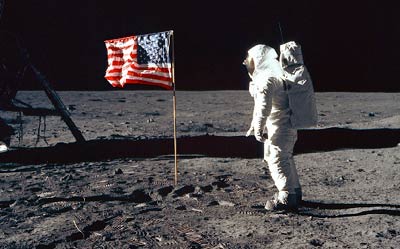

The foray of humankind into outer space, while still relatively young, has left its mark in outer space with sites such as Tranquility Base. As the men who flew to and walked on the Moon slowly pass into history, their activities on our one natural satellite will remain as a testament to that great achievement so long as steps are taken to protect them. To that end, legal mechanisms must be employed to facilitate their preservation and protection; however, in doing so, new laws must developed to address this important issue.

While present law for the preservation of antiquities and historical sites, both within the territories of the United States and in the world’s oceans, may provide a starting point for protecting sites such as Tranquility Base, they are by no means adequate to meet this task. Like new wine must be put into new bottles lest they break, new law must be created to address this new horizon of archeology and preservation, else efforts to legally protect historical sites will fall short of the growing reality that they could be altered or lost to us forever. If that happens, not only will those who flew and walked on the Moon eventually fade into history, but so will the permanent record of humankind’s peaceful arrival and departure from the Moon during the days of Apollo.

References

1 See Leonard David, “Space Archaeologists Call for Preserving Off-Earth Artifacts”, SPACE.Com, April 22, 2013.

2 As of this writing, the author has not been able to find a copy of this proposed law to review.

3 For example, the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals in Sea Hunt v. Unidentified Shipwrecked Vessel, 221 F.3d 634, 643 (2000), ruled that a sunken vessel carrying gold bullion, which was discovered in international waters off the coast of Virginia and identified as a Spanish vessel, was exempt from maritime salvage rules because the vessel was considered a federal vessel by Spain and was never expressly abandoned by the Spanish government even though it was missing for several centuries.

4 Talking Points on the Sunken Military Craft Act, http://www.history.navy.mil/branches/org12-12b.htm

5 Id.