NEAP: 15 years laterby Rex Ridenoure

|

| Benson decided to combine and focus his interests in space and natural resources with his business and political acumen towards an old goal: bringing the nearly infinite resources of space into the world’s economy. |

Benson had a degree in geology, had always been interested in astronomy and space, and had picked up considerable business savvy during his three decades as an entrepreneur. In the 1970s he was also engaged in political and environmental activism and knew how to get things done around the Beltway.

Jim Benson giving a keynote address at one of the many space conferences he attended. (credit: Rex Ridenoure, 1998) |

To relieve his early retirement blues, he decided to combine and focus his interests in space and natural resources with his business and political acumen via a new space firm that would blaze a path toward a goal expounded some 20 years before by Gerard O’Neill and others: bringing the nearly infinite resources of space into the world’s economy.

A passionate free enterprise advocate, Benson formulated his plans for the company in 1996–97, consulting with several leading experts on extraterrestrial resources, space science, and space technology and subjecting himself to a blizzard of space-related conferences, symposia, and events. He quickly established a good rapport in particular with John Lewis (then at the University of Arizona and author of a seminal text on extraterrestrial resources, Mining the Sky), Jim Arnold (an experienced lunar and asteroid scientist, then at the University of California San Diego), and NASA Administrator Dan Goldin and his Associate Administrator for Space Science, Wes Huntress. With these credible supporters encouraging him, and Benson’s natural talent for networking and public relations, he assembled an experienced and useful advisory board and an impressive list of contacts across multiple disciplines, rapidly establishing momentum for his new firm.

Benson was keen on the idea of “making commercial space happen” for those interested in an active and thriving space future, frequently reminding supporters and detractors alike that, “if we’re going to space to stay, then space has to pay.”

In less than a year after its founding in late 1996 as a privately-held Colorado corporation, Benson transformed SpaceDev into a publicly-traded company via a “reverse acquisition”2 so enthusiastic supporters of his vision might also share in the expected excitement—financially or otherwise—as SpaceDev shareholders. By October 1997, SpaceDev stock began selling over the counter, first under the moniker PSDM (the shell company subject to the reverse acquisition) and eventually as SPDV.

SpaceDev was not the first “NewSpace” firm, but was among the first of such companies founded by a wealthy computer/software/Internet entrepreneur who crossed over to space, years ahead of Bill Gross (BlastOff), Paul Allen (SpaceShipOne, then Stratolaunch), Elon Musk (SpaceX), Jeff Bezos (Blue Origin), one or both of the Google guys (Google Lunar X PRIZE, Planetary Resources), or Naveen Jain and Barney Pell (MoonEx). And let’s not forget Richard Branson (Virgin Galactic)—not quite from the same cloth as the others but a crossover success nonetheless.

SpaceDev, self-described by Benson as “the world’s first commercial space exploration and development company,” was one of the first NewSpace firms to garner a considerable amount of sustained domestic and international coverage in mainstream press and media outlets, driven in part by Benson’s charismatic and aggressive persona as well as his ability to articulate an unconventional and exciting vision for space. SpaceDev hit the streets right in the middle of the dot-com and telecom booms, when all things tech were culturally cool and financially hot.

SpaceDev logo, 1997. |

NEAP

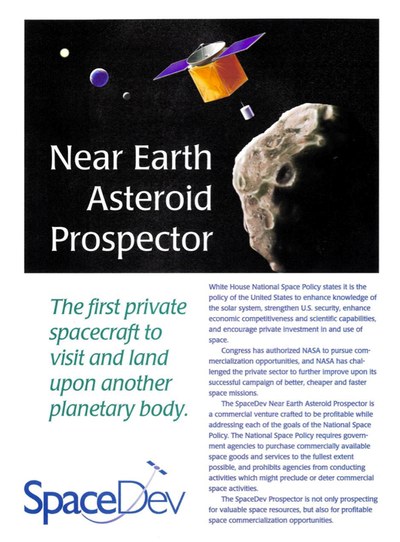

By late 1996 Benson had decided that SpaceDev’s first project would be to send a spacecraft to one of the many known near-Earth asteroids and, as would any serious geologist/businessman, characterize its makeup and composition as well as assess its commercial value. This project—an end-to-end space mission—became known as the Near-Earth Asteroid Prospector, or NEAP.

When NEAP was first announced in early 1997, Benson explained his bold objectives for the mission:

“NEAP will be the first private spacecraft to leave Earth orbit, the first private spacecraft to visit another planetary body, and the first private spacecraft to land on another planetary body. NEAP will carry sufficient instrumentation to size and categorize the asteroid, thereby allowing us to calculate a ‘street value’ for it. After landing, we will ‘stake’ any mining and patent claims we believe to be possible, and then will simply declare ownership of the trillion-dollar asset. This will help draw attention to the need to establish private property rights in space. Nine sources of income from NEAP have been identified, two of which could each pay for the entire venture. The entire venture will be privately financed, with no government grant money of any kind (necessary to ensure a pure private claim of the asteroid and its resources).”

Benson believed that minerals in space—or perhaps more likely water and ice, “concentrated, portable energy”—would create Earth’s first trillionaires. He surmised, as did others before him, that a key unsettled issue standing in the way of actually mining and cashing in on any asteroid or extraterrestrial body—for SpaceDev or any other entity—was that of property rights in space.

| Benson kicked off the review with, “Let the inquisition begin!” |

Rather than debate this issue at annual space conferences or at various academic and legal symposia as had been the ongoing practice for years, Benson’s more pragmatic approach was to simply send a commercially developed spacecraft to a desired target asteroid, touch the asteroid with the spacecraft by landing on it, and then claim it as private property. Right or wrong, he felt that this action would focus the discussion faster than any other approach. (His approach to the debate about life on Mars was similarly blunt: just send a probe there teeming with bacteria and organisms and be done with it.)

Benson was not an engineer and had no prior experience in the space arena, though over the years had developed an insightful appreciation for technology working in the computer and software industry. To facilitate the engineering required to move Benson’s visions toward reality, Jim Arnold’s connections had brought a small San Diego-based space systems engineering firm into the effort: Integrated Space Systems, led by co-founder and President Phil Smith. Most of the approximately 40 employees at ISS had worked on the Atlas rocket program at General Dynamics until Martin Marietta acquired the rocket family in 1993.

Smith, working with his ISS team and others, started assessing the feasibility of the mission concept in early 1997, and by fall 1997 had developed a reasonable baseline.

Early NEAP brochure, late 1997. (larger version) |

On November 11, 1997, SpaceDev issued its first Announcement of Opportunity (AO) for scientific, government, and private participation on a deep-space mission for “insured, published, fixed prices.” The AO highlighted participation opportunities on up to ten NEAP payloads: six science instruments and four “drop-cans”—small containers that would be ejected by the spacecraft en route to the target asteroid or onto the asteroid’s surface. Radio-science experiments using the spacecraft’s telecommunications system were also supportable. Rights to place logos on the spacecraft, launch tower, and project website were also to be sold, as were various media-broadcast and collateral rights (e.g., toys). SpaceDev-defined and funded payloads were reserved for three of the science instruments and one drop-can, offering data sets from these as “data-buy” opportunities. The rest of the open slots were marketed as FedEx-like rides to an asteroid. Attached to the AO was a catalog of fixed prices for these offerings and a set of commercial terms and conditions. Sales would be made on a first-come, first-served basis.

The AO projected a NEAP launch date between mid-1999 and mid-2000, with trip times to the target asteroids (1993 BX3 and 1996 FO3) between 9 and 15 months. The 18-month spacecraft build-test effort was projected to start in early 1998.

Validation

NEAP was subjected to its first thorough project peer review on Saturday, November 15th, 1997, hosted by Arnold at the University of California San Diego (UCSD) campus.3

Joining Benson, Arnold, Smith, and some of Smith’s immediate team were about fifteen invited reviewers, including Review Chair Tony Spear (who had just achieved near-celebrity status as Project Manager for the highly successful Mars Pathfinder mission at JPL), other JPL engineers, several staff members from the UCSD-based California Space Institute, several UCSD professors and graduate students, and engineers from aerospace firms such as Tether Applications, Aero Astro, Stellar Innovations, Applied Aerospace Structures, and Microcosm. Experts affiliated with AMSAT, ESA, and other universities also attended.

In brief introductory remarks Benson emphasized the commercial nature of the NEAP venture, the need to treat many project details (especially estimated costs) as proprietary to SpaceDev, and interest expressed in the project from the highest levels at NASA.

He then kicked off the review with, “Let the inquisition begin!”

Smith emphasized to the assembled group that the NEAP feasibility assessment phase was done and that the project had entered the system design phase. Various members of the team stepped through the baseline mission phases, requirements for the spacecraft subsystems, notional science instruments and commercial payloads, and overall concept of mission operations. The two target near Earth asteroids mentioned in the AO had been provisionally selected, though the desire was to eventually pick a more optimal target with a diameter of 200–800 meters from hundreds of candidates.

Benson addressed some of the non-technical issues such as fundraising, partnering, procurements, marketing and sales, insurance, and business risk. His revenue model included selling science data sets from each individual SpaceDev-controlled instrument, selling the unclaimed instrument slots, and commercial sponsorship of other notional payloads such as the drop-cans. He reported promising momentum from discussions with three possible customers, two from the US and one from Japan.

Benson also threw out an initial cost estimate for the mission: about $20 million, $10 million of which would be for the launch vehicle. The estimated cost for the spacecraft—several hundred kilograms fully loaded, to be built largely from already-available components—came to about $3.4 million. (In 2013 dollars these amount to about $30 million, $15 million and $5 million, respectively.)

| Most who attended the peer review were encouraged, not the least of which Benson. He stepped up the effort a notch—still using his own funds—and authorized Smith and team to dive into another level of detailed planning for the mission. |

Spear was encouraged by the project’s technical status, and concluded that there were no technical showstoppers to SpaceDev’s mission and system designs. He and others at the meeting expressed concerns about pinning down the launch vehicle choice and interfaces; nature and location of the project team; choice of science instruments and other payloads; methods for estimating project development schedule and costs; the fundraising process itself; perceptions of prospective customers about the team’s credibility and heritage of the spacecraft design; project margins and risk posture; deep-space tracking and navigation plans; and possible tie-ins with ongoing NASA programs.

Acceptance

Most who attended the peer review were encouraged, not the least of which Benson. He stepped up the effort a notch—still using his own funds—and authorized Smith and team to dive into another level of detailed planning for the mission. He also worked out a deal with Smith and the other ISS co-founders to merge ISS into SpaceDev, which was completed February 1998 and precipitated moving SpaceDev from Colorado to the San Diego suburb of Poway. Additional full-time staff added in the early months of 1998 brought the employee count up to several dozen, covering most aerospace and business disciplines.

Benson’s claim that a quality low-cost deep-space mission could be done was bolstered at this time by the ongoing mission operations of the NASA-funded Lunar Prospector mission, which had reached lunar orbit in early 1998 and was performing quite well. This mission was a prototype of what Benson had in mind, having been developed and marketed first as a commercial mission before being selected by NASA as one of the Discovery program missions.

NASA saw the connection too. By early 1998, Wes Huntress at NASA’s Office of Space Science and his key staff at the Solar System Exploration Division felt confident enough in the progress of the NEAP team that the mission’s catalog of data-buys and payload slots was offered as a set of “Mission of Opportunity” candidates for NASA’s Discovery and MIDEX programs. “A number of people had told me they wanted to start space businesses,” Huntress said, “but they always wanted government money. Jim said he didn’t want any government money. He just wanted the opportunity to compete. That got my attention.”4

By March 1998, the NEAP team had drafted a 40-page Project Overview document5 to consolidate what was known about the baseline mission and system design. It was tailored to provide prospective customers with sufficient information to justify participation in the mission and also to summarize top-level mission and engineering requirements to help facilitate the detailed design process. Several cycles of editorial updates to this summary were completed through the spring, including significant inputs from an internal NEAP mission review held on April 18th. By May it represented a good snapshot of the project. The contents included:

- Background on SpaceDev and its commercial approach to deep-space exploration and utilization

- NEAP mission synopsis and project status

- Mission requirements

- Mission description

- Preliminary spacecraft description

- Participation opportunities

- Payload user’s guide

- AO

- NEAP FAQs

- NEAP management and key personnel

- SpaceDev Advisory Board members

During this time, the target asteroid and associated launch dates were in flux. In March, the near-Earth asteroid 1996 XB27 (about 175 meters in diameter) was the new target, selected from over 400 candidates. This choice shifted the launch to three opportunities between October 2000 and February 2001, driven more by celestial mechanics than anything else. Arrival at the asteroid would be no later than June 2001. The total mission duration was 12 months: up to eight months of cruise, a one-month primary mission at the target, and a three-month extended mission phase.

Following a detailed review of target options in May, a tantalizing new target surfaced: near-Earth asteroid 1982 DB—more commonly called 4660 Nereus—implying acceptable launch dates between April 2001 and January 2002 and arrival at the carbonaceous-type body no later than May 2002. Mereus was easier to rendezvous with, in terms of propulsion, than orbiting the Moon, and at over 300 meters in diameter it would amply fill the bowl of a typical football stadium. Prominent planetary scientists, Spear, and Benson all came to view a mission to Nereus as the quintessential near-Earth asteroid mission.

| When pressed for a reaction to the prospect that a commercial firm might visit an asteroid she discovered and claim it as private property, astronomer Elanor Helin replied, “My visceral reaction was ‘heaven forbid, not on your life!’” |

Detailed design of the three-axis-stablized NEAP spacecraft, weighing 350–500 kilograms, was well underway by this time, and hundreds of candidate suppliers had been identified for the various hardware components, software packages, and test-related equipment and services. Subcontracts to various engineering services firms were being let for detailed analyses of the spacecraft guidance, navigation, and attitude control subsystem; telecommunications subsystem; and various mechanical and structural elements. Detailed designs for the three SpaceDev-supplied science instruments—a Neutron Spectrometer, Alpha Proton X-Ray Spectrometer, and Multi-Band Imaging Camera—were underway, as was the design for the standard drop-can system. Fifteen different options for the launch service were being assessed and price quotes were starting to come in.

A May 6, 1998, SpaceDev news release announced that seven scientific principal investigators had filed notices of intent with NASA to propose their own concepts for seizing the NEAP opportunities. These filings were from three different NASA centers, three different US universities, and the Naval Research Laboratory. Each proposal, if accepted, would lead to $10–12 million in revenue for the firm.

Benson was adamant about applying the purely commercial business practices he had fine-tuned at his software businesses to SpaceDev, seeking to avoid the tentacles of the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FARs), which he regarded as a major impediment to effective and efficient business and project execution. “No FARs!” was one of his favorite statements in speeches and presentation charts. He saw strong parallels between what was about to happen in space science and what already happened with the mainframe-to-PC evolution in the computer industry, and was eager to be one of the leading champions for this change.

Notably, Benson’s plan for NEAP (and other similar missions in a planned series, launching about once per year) called for financing the entire mission up front via traditional equity financing. Payload sales from the commercial catalog would lead to down payments (typically one-third of the total line-item price), but these funds would be held in escrow until SpaceDev completed the required mission objectives for each payload, at which time the remaining balances from each customer would be due to SpaceDev. No government subsidies were allowed, though individual payload slots for science investigators could be funded via government sources, but only if all of SpaceDev’s standard commercial terms and conditions were followed, as if the government were simply buying another personal computer, box of repro paper, or pencil.

Further, the Project Overview for prospective investigators emphasized, “it is the responsibility of the science team to adequately communicate to the NASA review panel that this is a NO RISK mission.” Why this claim? Because the launch and mission would be insured, just as most typical commercial Earth-orbiting missions had been for decades (and still are). This important feature of the NEAP project (and future envisioned SpaceDev projects) distinguished it from all prior deep-space missions.

Noting the rapid progress on the engineering front and enthusiastic responses from the science community, Benson decided to make another fresh cut of the NEAP mission and system design, announcing in a June 8th SpaceDev press release that a “dream team” of outside experts led by Tony Spear would be tapped to baseline a new mission profile and spacecraft design, with Nereus as the target. Details on this new project baseline would then be used by the investigators in their Mission of Opportunity proposals to NASA, due a few months hence. “This is a wonderful and important possibility,” noted Benson, “because Nereus will fly by the Earth just before the rendezvous opportunity, only 0.29 AU [astronomical units] away. If we go to Nereus, a type C asteroid, it will be the first time that close-up ground-based instrument findings can be correlated with instruments flown to and dropped onto an asteroid.”

When pressed for a reaction to the prospect that a commercial firm might visit an asteroid she discovered and claim it as private property, astronomer Elanor Helin replied, “My visceral reaction was ‘heaven forbid, not on your life!’”6