You’ve come a long way, baby!by Dwayne Day

|

| The letter is simultaneously shocking and yet totally familiar, and also consistent with other documentary evidence from that time period. |

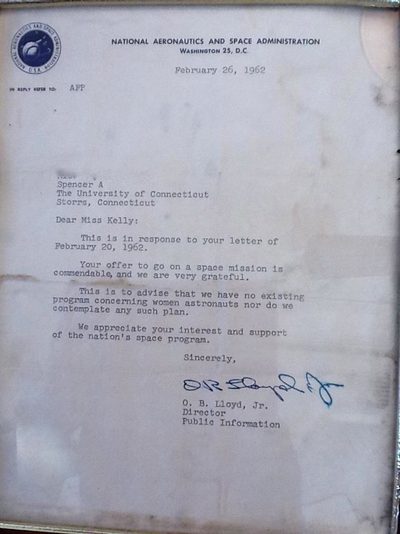

In January of this year, somebody posting to the popular and raucous Internet discussion group Reddit.com shared an interesting scanned image of a letter they claimed had been sent by NASA to their friend’s mother in February 1962. The letter was apparently in response to college student Ms. Kelly’s query about going on a space mission. “This is to advise that we have no existing program concerning women astronauts nor do we contemplate any such plan.” The response from NASA was simple and to the point and totally accurate, for the agency was repeatedly being pressured to allow women to become astronauts, and had repeatedly refused, although up until summer 1962 agency officials had treated the issue as a minor annoyance that did not require high-level attention or formal policy declarations.

A 1962 letter from NASA to wa woman stating that NASA had no plans to accept female astronauts. [larger version] |

Reddit discussions can go on and on and be filled with inanity, profanity, sexism, racism, and worse. But this posting in January garnered approximately three hundred comments and was then forgotten. It was not until last week, when another poster shared the same image, that it suddenly attracted a lot more attention—“going viral” in the overused jargon of the modern era—this time gathering thousands of comments, many of them sexist and ribald. Such are the ways of the Internet.

People don’t usually frame their job and college rejection letters for posterity, so it is rare that something like this exists. Yet, considering the growing controversy over this issue at that period of time, it is not completely unusual. The letter is simultaneously shocking and yet totally familiar, and also consistent with other documentary evidence from that time period. NASA did not accept women as astronauts for the first two decades of its existence. It was not until the 1980s, 25 years after the agency was created, that the first American woman flew in space. And any student of space history should be well aware of the “Mercury 13” women pilots who underwent a series of aerospace medical tests similar to those of the male Mercury astronauts in the early 1960s but were never seriously considered as astronaut candidates. Anybody who has read the books that have focused exclusively on this subject, or have devoted considerable attention to it, should also be familiar with the contempt with which those women were treated.

Last month James Oberg wrote an article about Hillary Clinton’s claim that she was informed by NASA in the early 1960s that NASA was not accepting female astronauts (See: “‘We don’t take girls’: Hillary Clinton and her NASA letter”, The Space Review, June 10, 2013). This resulted in predictable and regrettable partisan bickering and chest-thumping. Although Mr. Oberg tried to make the argument that such a blunt letter squashing a young girl’s dreams was unlikely because one had not turned up during his limited research—which the January 2013 Reddit posting refutes—he failed to cite any of the exhaustive academic literature on the subject of women astronauts. Had he done so, he would have had to note that NASA, other government officials, and the culture at large were all sending plenty of blunt messages to women about opportunities in space. This academic literature also demonstrates that from about mid-1961 until mid-1962 there was an internal struggle at the agency to figure out what to do about the messages NASA should be sending.

See, for instance, Margaret Weitekamp’s Right Stuff, Wrong Sex: America’s First Women in Space Program, or Martha Ackmann’s The Mercury 13: The True Story of Thirteen Women and the Dream of Space Flight, or Joseph D. Atkinson, Jr. and Jay M. Shafritz’s The Real Stuff: A History of NASA’s Astronaut Recruitment Program, or Colin Burgess and Paul Haney’s Into that Silent Sea: Trailblazers of the Space Era, 1961–1965. All of these books deal with that crucial time period.

For example, according to Atkinson and Shafritz, on June 19, 1961, G. Dale Smith, NASA Assistant Director for Program Planning and Coordination of the Office of Life Science Programs, wrote a memo to George M. Low, Director of Spacecraft and Flight Missions of the Office of Manned Space Flight. His memo stated:

“There are a number of letters being sent to Headquarters by women who wish to become astronauts. I hope you will have ideas on answering these letters. The medical portion of a selection and training program is but a guide in selecting physically and mentally qualified people, and as you know, women fall within the physically qualified; therefore, there must be other valid reasons why or why not we are to use women in our space flight program.” – The Real Stuff, p. 90

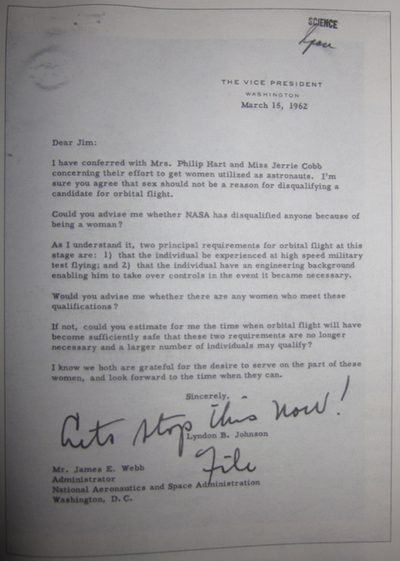

But the best example of negative correspondence on this subject at the time is a letter that was not sent. It was discovered by Margaret Weitekamp in the LBJ Presidential Library. It was a draft letter written by President Johnson’s assistant Liz Carpenter in response to the increasing media attention devoted to women like Jackie Cochran, Jerrie Cobb, and the other so-called “Mercury 13.” For over a year, those women had been publicly speaking and agitating about the issue, and two of them were about to meet with Johnson. In advance of his meeting with the women, Carpenter drafted a letter for Johnson that asked NASA administrator James Webb to look into the issue. The draft letter, dated March 15, 1962 (and reprinted in Ms. Weitekamp’s book), stated:

I have conferred with Mrs. Philip Hart and Miss Jerrie Cobb concerning their effort to get women utilized as astronauts. I’m sure you agree that sex should not be a reason for disqualifying a candidate for orbital flight.

Could you advise me whether NASA has disqualified anyone because of being a woman?

As I understand it, two principal requirements for orbital flight at this stage are: 1) that the individual be experienced at high speed military test flying; and 2) that the individual have an engineering background enabling him to take over controls in the event it became necessary.

Would you advise me whether there are any women who meet these qualifications?

If not, could you estimate for me the time when orbital flight will have become sufficiently safe that these two requirements are no longer necessary and a larger number of individuals may qualify?

I know we both are grateful for the desire to serve on the part of these women, and look forward to the time when they can.

Sincerely,

Lyndon B. Johnson

Johnson chose not to send the letter. Instead, in large script he wrote at the bottom “Lets stop this now! File” Liz Carpenter duly filed the letter and it remained unknown for four decades, until Ms. Weitekamp unearthed it.

A draft letter from LBJ to NASA about female astronauts that he elected not to send, scrawling “Lets stop this now! File” on it. [larger version] |

This exchange, essentially between Johnson and one of his female assistants, is really just another variation of the NASA letter sent to Ms. Kelly only a few weeks earlier that there was no program for accepting women astronauts, and there would be no program for accepting women astronauts in the future. Indeed, similar letters were regularly sent by NASA officials to Jerrie Cobb, such as another one found by Ms. Weitekamp written in April 1962 by Robert Gilruth, NASA’s director of the Space Task Group. Gilruth stated “We cannot select women just because they are women.” Gilruth added that if a reason eventually surfaced to consider women, then NASA would consider women. But no reason currently existed. (Weitekamp, p. 139.)

| The letter to Ms. Kelly is entirely consistent with the jokes made at the congressional hearings, LBJ’s blunt rejection of the issue, other comments made by other NASA officials, and Ms. Clinton’s 2009 comment. |

On July 17 and 18, 1962, the House Committee on Science and Astronautics held public hearings on the prospect of women astronauts. The first day featured Jerrie Cobb and Jane Hart, one of the other members of the “Mercury 13.” The second day featured NASA official George Low and astronauts John Glenn and Scott Carpenter. The hearings made clear that women were not going to be considered as astronauts. The hearings included many patronizing jokes by the men present, including the astronauts, about women in general. The Mercury 13 group’s agitating started to die down after this publicity, but Jerrie Cobb, in particular, continued to speak publicly about the issue. Even after Valentina Tereshkova flew into space in June 1963, the argument continued.

The letter to Ms. Kelly is entirely consistent with the jokes made at the congressional hearings, LBJ’s blunt rejection of the issue, other comments made by other NASA officials, and Ms. Clinton’s 2009 comment. But more importantly, it is entirely consistent with everything else we know about attitudes towards women in American society from that time period. Many jobs and opportunities were closed to women in the early 1960s and remained so until over a decade later. When new opportunities finally became available for women in the 1970s they did not simply happen due to the sudden benevolence of men, or often simply changes in policy—agency and department heads suddenly deciding to allow women—but only as a result of women raising a ruckus, lobbying the government, and pressuring men into changing the laws. For instance, it was not until 1976—after an act of Congress—that women were finally allowed to enter West Point, the US Naval Academy, and the US Air Force Academy. It is not hard to believe that a young girl, writing a letter to the commandant of West Point in 1961 or 1962, would receive a letter in reply telling her that they don’t accept girls and didn’t anticipate doing so in the foreseeable future.

Certainly laws, policies, opportunities, and yes, attitudes, changed between the early space age and the early 1970s. Just how far they have changed can be seen in an almost offhanded comment in an article written by space author Martin Caidin in a 1958 men’s magazine, four years before the subject came to a boil in Washington.

Caidin was a prolific author during his lifetime, producing over fifty books and a thousand articles. He wrote the book Cyborg that eventually was turned into the TV show The Six Million Dollar Man, and another book that eventually became the movie Marooned. Caidin lived near Cape Canaveral, went out drinking with astronauts, and flew a big rumbling airplane for fun—a man’s man, if you will. He wrote a lot of non-fiction in addition to his novels.

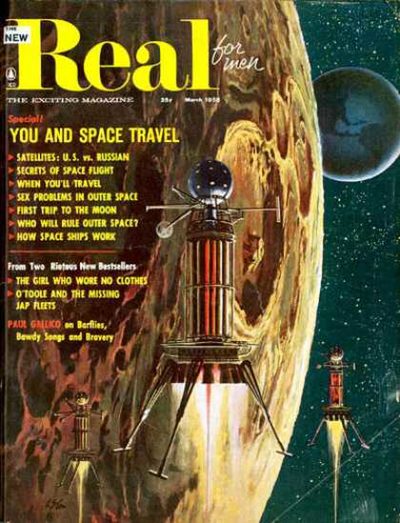

In March 1958 Caidin published an article in Real, “The exciting magazine for men.” Real was of a genre that today is probably best typified by magazines like Maxim. It was middlebrow, not exactly classy reading, with a hint of smut. Caidin’s article, “What You Should Know About Space Travel,” got the cover of the March 1958 issue, with a striking illustration by Louis Glanzman depicting three spaceships over the Moon.

“What You Should Know About Space Travel” is a well-written, comprehensive overview of the subject. Because he was writing for a men’s magazine, he had to include something to pique the interest of the average horny male, and so the cover included several of the questions that Caidin answered inside, including “Sex problems in outer space.”

Here is what Caidin wrote:

Some space ship flights might last several years, and the crewmen would be at the prime of life. If these men are committed to a small cabin for years, what about the enormous sexual problems which will arise? You simply can’t cut off a sex drive by ignoring it.

It’s one of their biggest problems. Frankly, the choice is obvious. Oh, you can, by the use of a sharp scalpel, simply remove the source of the sex drive. Naturally, this won’t work; no man who is a man will submit to castration. If you ignore the problem, you’re letting yourself in for emotional dynamite and homosexuality—and that is not acceptable. The only solution, of course, will be to provide mixed crews. There’s no reason in the world why a woman wouldn’t do as well as a space ship crew member as a man. Here the problem lies not with the crews, either the men or the women, but with the American public and religious groups which will scream to high heaven at the mention of the fact that man has a strong sex drive which cannot be bottled up like peas in a can. Perhaps the authorities will “marry” off opposite sexes of the crew members. But you can bet your bottom dollar that this is one of the major problems of space flight which, just as soon as we’re ready for trips of long duration in space, will have to be met.

Put simply, in 1958 Caidin thought that women would eventually become astronauts so they could provide sexual services to the male astronauts, not because they inherently had anything to contribute.

| The early years were dominated by men sometimes gently, sometimes patronizingly, and sometimes bluntly discouraging women from thinking that they ever could become astronauts. |

Fortunately, things got better. Slowly. The politics and the laws didn’t change quickly in large part because the culture didn’t change. If you watch the classic 1968 movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, look for the women. There are only a few. Notably, the American female astronauts serve the men coffee.

It took time. It was not until 1978—two years after the military academies admitted women—that NASA announced its first female astronaut candidates. Sally Ride did not fly until 1983. A woman did not command a shuttle mission until 1999. But it was a long slow fight, and the early years were dominated by men sometimes gently, sometimes patronizingly, and sometimes bluntly discouraging women from thinking that they ever could become astronauts.