It’s not bragging if you do itby Dwayne Day

|

| This footage shown as the launch happened was far better than coverage of American launches and demonstrated a keen Chinese understanding of the importance of good imagery to show off their work. |

Last Sunday’s CCTV coverage of the Chang’e-3 launch was quite sophisticated. The network had correspondents at the launch site and at the control center. They had a commentator in the studio asking rudimentary questions of an expert during the launch sequence. The questions and the expert’s answers were intended for a general, non-space-savvy audience. They also had animations of the lander and rover, and segments focusing on the development of the spacecraft, including interviews with engineers who had built individual parts. For instance, one young engineer had worked on small electric motors for the spacecraft. He acknowledged that there was nothing very sophisticated or exciting about the motors, but that they were vital to mission success.

Perhaps the most startling aspect of the coverage was the launch footage, including the use of high-resolution onboard cameras to show the rocket’s ascent and staging events. The spacecraft separation, including small thruster firings, looked spectacular. This footage shown as the launch happened was far better than coverage of American launches and demonstrated a keen Chinese understanding of the importance of good imagery to show off their work. It was a far cry from Cold War days when the Soviet Union often only acknowledge successful launches after they had happened, rarely admitting their failures, and never showing their events live.

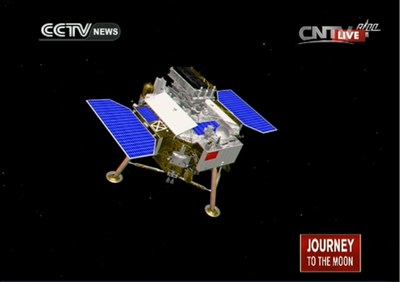

An image of the Chang’e-3 spacecraft seen departing from its upper stage. China provided live coverage of the launch with stunning footage like this to show off what it can do in space. (credit: CCTV) |

As propaganda—and on one level it was propaganda—it was an outstanding performance. Nobody was singing the praises of the Chinese Communist Party or mentioning Chairman Mao. They were just reporting the facts, which were impressive. As China has gained in self-confidence, they no longer need to engage in the kind of braggadocio used in the past, or which is still prevalent in North Korea. This was the cool confidence of a professional space power.

The person who provided the mission commentary was Xu Yansong of the Asia-Pacific Space Cooperation Organization (APSCO). His English was nearly flawless, and other than a few minor errors his comments were illuminating and on point. As it turns out, APSCO, formed in the early 1990s, is actually a Chinese-led organization headquartered in Beijing. Its members include Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iran, Mongolia, Peru, and Thailand: not exactly first-tier space powers. APSCO is devoted to “education and training,” but its existence demonstrates China’s aspirations to lead other countries, to use its space capabilities as a method of influencing its neighbors.

| Space is a great soft power resource for China, but it is certainly not the only one or even the best one. |

This is not unusual. Both Japan and India also lead similar organizations that include smaller partners. In 1995 India helped to create the Center for Space Science and Technology Education in Asia and the Pacific, also with an education and training focus. It runs training seminars and education courses to fifteen nations, including three that belong to the APSCO. In 1993, Japan formed the Asian-Pacific Space Agency Forum with a primary focus on providing advance warning and coordination for natural disasters. It has 20 members, including six that are also part of APSCO. As Fordham University professor Asif Siddiqi pointed out in his paper “An Asian Space Race, Hype or Reality?” these organizations overlap somewhat in their membership and their functions, but although they have similar but not identical missions, they result from the fact that the bigger powers in Asia are trying to establish their own bases of influence in the region.

Using space for international relations purposes dates to the early 1960s and the Cold War. Both the United States and Soviet Union flew astronauts from their allied countries in space. The American experience is long and distinguished, dating to soon after the country launched its first satellite and then offered to help its allies do the same, initially with American rockets and later with their own. The United States initiated space cooperation with Britain, Canada, Japan, India, and other countries. Starting in the 1970s, the United States included Europe in its Space Shuttle program, having European nations build Spacelab for conducting research missions inside the shuttle payload bay. In the early 1980s, Ronald Reagan started a space station program that included many NATO allies as well as Japan. By the 1990s, President Clinton turned the space station program in a different direction, using it as one tool to bring Russia into closer ties with the West, and to help stabilize some of its industries. Often cost and other concerns were second in importance to strengthening political ties with partners. Rather surprisingly, the Obama Administration has not sought to use civil spaceflight as an international tool. In fact, the administration’s cancellation of cooperation with Europe on robotic Mars exploration, primarily a budget decision, has had the opposite effect, driving Europe into closer cooperation with Russia, and perhaps China.

Although China has an extensive military space program, the country’s leadership has shown signs of recognizing the benefit of using its civilian projects for international purposes, with APSCO being just one of numerous initiatives. China’s scientific space program offers it substantial appeal to other countries. China has announced that when their space station is up and running they intend to invite international partners to come on board, although it is not clear if they will offer the kind of opportunities, such as developing major hardware, that the United States offered its partners decades ago. And as China continues landing spacecraft on the Moon—they have plans for at least two to three landings after Chang’e-3—they could also hold out a hand to countries that may be interested in developing their planetary space skills as well.

Space is a great soft power resource for China, but it is certainly not the only one or even the best one. China’s size as a potential market is a major resource, and the Chinese government has already made clear to many countries that if they want to sell goods to China’s rapidly growing consumer market, they need to be nice. Similarly, China has great financial resources, and countries that want Chinese loans and other development assistance may also have to bend to their will on international issues.

| At the same time that China was demonstrating its space capabilities with the Chang’e-3 launch, it was also taking actions on the international stage that once again reminded the rest of the world in general and its neighbors in particular that China can use “hard power” to pressure others into doing what you want. |

However, space does have benefits as a highly visible technological endeavor even today, when it is an activity humans have been engaging in for over six decades. For many countries, even heavily industrialized ones, there is an allure to being able to touch other worlds or demonstrate an ability to answer some of the bigger scientific questions like the formation of the solar system. China is planning additional robotic lunar missions after Chang’e-3, and could offer opportunities to other countries to come along, possibly even to American allies. Just as Europe is attracted by Russian offers of assistance with Mars missions, they might be enticed by a Chinese offer of a ride to the lunar surface for their scientific instruments or even a rover.

But the counterpoint to this possibility is China itself. The country has many interests and at the same time that China was demonstrating its space capabilities with the Chang’e-3 launch, it was also taking actions on the international stage that once again reminded the rest of the world in general and its neighbors in particular that China can use what Joseph Nye referred to as the more easily understood “hard power” ability to pressure others into doing what you want. Only a few days earlier China declared an “air defense identification zone” in the East China Sea, requiring any aircraft entering the zone to identify themselves to Chinese airspace monitors. Because the zone includes territory of other countries, and because such a zone is a prelude to demanding that aircraft seek permission to fly in the airspace, it was a provocative act and has unsettled the region.

The outcome of China’s latest exercise of hard power in its region is not yet clear, and, even so, it is probably only just another step in a much longer-range strategy for the region. But it is yet another reminder that the peaceful actions of nations in space are still governed and often overshadowed by their interests back on Earth.