What’s a space exploration program for?by Jeff Foust

|

| “It’s time to set aside the proposed asteroid mission and instead focus NASA’s direction on leading a return to the Moon, before our partners commit their resources to another country,” Wolf wrote. |

In fact, heads of a number of space agencies will be meeting in Washington—at the Reagan Building, a few blocks away from the White House—later this week for a space exploration conference organized by the International Academy of Astronautics. That “Summit on Exploration,” through, is not expected to result in any major new initiatives, given that the International Space Exploration Coordination Group updated its Global Exploration Roadmap just last year, vaguely endorsing both asteroid and lunar human missions as precursors to eventual Mars missions.

The ongoing debate about where to go—as well as when, why, and how—is indicative of a deeper problem with space exploration, particularly human spaceflight. “It’s really in human spaceflight that you have existential problems,” said Scott Pace, director of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University, during a panel last month on Capitol Hill organized by the Marshall Institute.

That panel was tied to the release a new book by the institute, America’s Space Futures: Defining Goals for Space Exploration. In it, Pace and several other experts offer their own visions for what the US should be doing in space, particularly, but not exclusively, involving human spaceflight. “The book had its origins in conversations” about the space program, including why have a space program at all, said Eric Sterner, a Marshall Institute fellow who was the book’s editor. “We can’t always come up with a very good answer.”

In the book, Pace and several other experts offered their own distinct visions of what a space program should look like and its underlying rationales. For Pace, that means a program that is both aligned with national priorities and has geopolitical significance. “It’s hard to sustain focus beyond multiple political administrations” for large space programs, he said. “The only way to sustain a focus across multiple decades is to make sure your program, particularly human spaceflight, is aligned with enduring national interests.”

In the case of the US, he said, the nation is particularly dependent on space assets for national security and the economy, and thus has “a great strategic interest” in keeping the space environment stable. Human spaceflight can serve that need, he said, through international cooperation on future space exploration efforts.

The current administration, he argued, hasn’t done a good job in this respect, citing NASA’s termination of plans to cooperate with ESA on the ExoMars mission and its pursuit of asteroid and Mars missions that are beyond the capabilities, and of little interest, to potential international partners. “The opportunities for international cooperation are actually much broader” for the Moon than other destinations, he argued.

| “The only way to sustain a focus across multiple decades is to make sure your program, particularly human spaceflight, is aligned with enduring national interests,” said Pace. |

In the book, Pace is critical of the administration’s emphasis on a “capability driven” space program: in an era of constrained budgets, “such an approach avoids both the need to make a decision to cancel human space flight, or, if it is not to be cancelled, the need to specify what it is that human space flight should accomplish.” But another contributor to the book, James Vedda of the Aerospace Corporation, feels differently, arguing that it’s essential for to work in the short- to medium-term to develop capabilities to live and work in space.

“The capability-driven approach has to include asking the big questions, and figuring out how to ask them,” Vedda said at the panel session. Those big questions, he said, include whether humans can survive in space in the long-term, and make use of the material and energy resources of space. “Those kinds of questions have to be posed so that our goals are not where do we fly to next—where do we fling our astronauts—but how do we add new capabilities?”

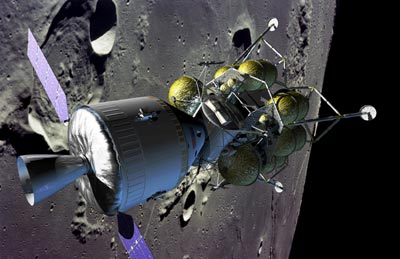

Vedda argues that this can be done by turning cislunar space into an “industrial park” where we develop the capabilities to live and work in space for the long-term. Only after developing those capabilities, he said, should we plan to move further out into the solar system.

Another contributor, William Adkins of Adkins Strategies LLC, also puts an emphasis on developing capabilities, but in the form of enhanced technology development. “Basically, our technology base has been over-grazed and under-nourished,” which threatens our leadership in space, he said at the panel session. “It’s not just a NASA problem, it’s a national problem.”

Adkins argues for a greater emphasis on research and development within NASA, including a mix of basic and applied research, technology development and demonstration, and flight missions that encourage the use of new technologies. “To accomplish this,” he writes in the book, “research and technology advancement must become as important as performing flight missions.”

| “Whichever country achieves cheap access to space first—there’s no guarantee it’s going to be America—is going to start a virtuous cycle that will deliver tremendous economic and security benefits to that nation,” Miller said. |

“The first step, and probably the hardest step, is culture, and it’s notoriously difficult to change,” he said. He advocated a hybrid organizational approach, borrowing from both the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA), the precursor to NASA that worked with other government agencies and industry on aeronautics advances; and DARPA, which contracts out its cutting-edge projects.

Charles Miller of NextGen Space LLC said there should be an emphasis on cheap access to space. “Whichever country achieves cheap access to space first—there’s no guarantee it’s going to be America—is going to start a virtuous cycle that will deliver tremendous economic and security benefits to that nation,” he said. “Cheap access is the connection between space commerce and space power.”

While lowering launch costs has long been a goal for NASA and other space programs, the problem with them, he said, has been a “central program mindset.” Instead, he argued for a more decentralized approach, with multiple partnerships with industry rather than betting on a single system.

That concept is supported by early aviation history, Miller argued. A few years after the Wright Brothers’ first flight—entrepreneurs beating out the government-supported Samuel Langley—France took the lead in aviation. That was, he said, because of a large number of entrepreneurs competing with each other. “They had what was really the Silicon Valley of aviation,” he said, which the French government was supporting by purchasing large numbers of airplanes.

The book, Sterner said, was something of a thought experiment about what a space exploration program could be. “Is it politically feasible,” he asked his fellow co-authors at last month’s panel, “to reorient it to something as visionary or strategic or aggressive as the programs that you laid out?”

“It’s perfectly possible for the US to do the right thing eventually,” Pace responded. “There’s nothing in engraved in stone that we have to keep doing stupid things.”

However, decisionmakers first have to come to the consensus that they are doing “stupid things” and reorient themselves to whatever the “right thing” in space exploration policy should be. As America’s Space Futures: Defining Goals for Space Exploration illustrates, there is no shortage of ideas of what that right thing should be, leveraging some combination of technology development, commercial partnerships, and geopolitical imperatives. There’s little sign, though, that policymakers will adopt any those ideas any time soon.