Everest, the camps, and the Sherpasby Derek Webber

|

| Reaching the geopotential plateau is our new Everest. I believe what we need for success is the equivalent of the Camps and the Sherpas. |

The Moon story is well known. It was technically achieved by a succession of ever more capable spacecraft—Mercury, Gemini, Apollo—the crews who took the risks of flying them, and the 400,000 people who built the infrastructure. Of course, there was also the little matter of money, and the Apollo program cost the US taxpayer up to 5% of the federal budget throughout the sixties. Since we can no longer entertain the idea of spending 5% of the federal budget for NASA (current NASA budgets are about 0.5%), maybe there are lessons from the Everest example that can help us see the way forward.

Tensing Norgay was a Sherpa. Sherpas were contracted by mountaineering expeditions both as mountain guides and for hauling the food, water, oxygen, and other supplies up the mountains of Tibet. First, a base camp was established. Sherpas made sure it was kept fully stocked by making repetitive trips from the local villages. Then a succession of ever higher camps was established, and the Sherpas continued their role of ferrying supplies ever higher up the mountain. As they got higher into the thinning atmosphere, the work got more and more exhausting, and the hardest step of all was the setting up and provisioning of the camp just below the summit. But once that had been done, the assault team had its chance—and if they were unsuccessful a backup team could always try from this same setting-off point.

This, of course, I am proposing as a metaphor for how we can regularly climb out of Earth’s gravity well and proceed onwards with exploring interplanetary space. Reaching the geopotential plateau is our new Everest. We have already done it in the sixties, of course, but that was the 5% solution. I am looking for the 0.5% solution. I believe what we need for success is the equivalent of the Camps and the Sherpas.

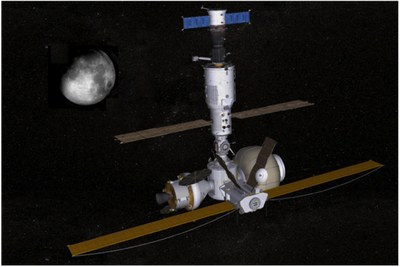

We already have the Base Camp, and boy, what a base camp it is. Our Base Camp is in LEO, where we have been refining our capabilities for over 50 years, and is now represented by all the comforts and facilities at the International Space Station. But what is missing is the perhaps less salubrious high altitude camp just below the summit, i.e., just at the edge of Earth’s gravity well. If we had a camp there, and it were kept supplied with the right assortment of items needed to make the “final assault” possible, interplanetary travel could become a matter of routine. And following our analog, what are the “Sherpas”? We need a fleet of tugs regularly traveling between “base camp” and the “high altitude camp”, that is, between LEO/ISS and the high altitude station (call it “Gateway Earth”).

| No doubt many would be content to stay at Base Camp forever, but that is not what base camps are for. We are supposed to use them to move on upwards. |

With this perspective, it does not matter where or when we reach the “ultimate objective”, because with the Gateway Earth and the supporting tug infrastructure in place, we shall thereafter have ready access to the entire geopotential plateau, and all destinations from that point onwards would consequently require relatively little energy—whether it be for the Moon, Mars, asteroids, Moons of Jupiter, etc. We would have put in place the equivalent of the series of camps up Everest, or the Interstate Highway System, to provide the next generation with what it needs to press onwards.

There are, of course, always limitations to analogs, and this Everest one is no exception. For the space equivalent we do not need the series of camps at higher altitudes, just the base camp and the one at the edge of Earth’s gravity well. But we do need to make sure that we have our Sherpas ready to do the job of ferrying supplies and people between the base camp and Gateway Earth. We need the tugs—reusable and refuelable—to sustain the outpost at Gateway Earth. I suspect that space tourists would be interested in that journey, and therefore Gateway Earth and the tugs can probably be partially funded commercially.

We have now been at Base Camp for over 50 years, and there is no denying that it is an excellent base camp, especially as now represented by the ISS. No doubt many would be content to stay at Base Camp forever, but that is not what base camps are for. We are supposed to use them to move on upwards. Let’s build our Gateway Earth camp, and engage our Sherpa tugs, to provide the highway into interplanetary space for succeeding generations.