Boeing displays CST-100 progress at Kennedy Space Centerby Anthony Young

|

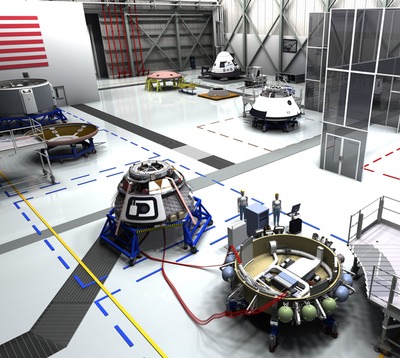

| The partially refurbished former OPF-3 was a dramatic sign of the changes taking place at Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in support of commercial space activity. |

On hand for the event was Senator Bill Nelson and several executives from Boeing, including John Elbon, Vice President and General Manager of Space Exploration; John Mulholland, Vice President and General Manager of Commercial Programs; and Christopher J. Ferguson, Director of Crew and Mission Systems for the company’s Commercial Crew Program. Ferguson, a former astronaut, was pilot on Space Shuttle mission STS-115 (Atlantis) and commander on STS-126 (Endeavour) and STS-135 (Atlantis)—the final shuttle mission.

The partially refurbished former OPF-3 was a dramatic sign of the changes taking place at Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in support of commercial space activity. Space Florida, the state’s aerospace economic development agency, signed an agreement with NASA in October 2011 to arrange for the financing to perform the extensive reconfiguration, structural removal, and refurbishment of the OPF-3 for commercial purposes. Space Florida’s customer for this project is Boeing, which wanted the facility for the CST-100 Crew Capsule Processing Facility.

“Partnering with Space Florida to enable commercial space operations at Kennedy Space Center will help NASA maintain facilities and assets while supporting our nation’s space objectives and expanding opportunities for the US economy,” KSC Director Bob Cabana said at the time.

The refurbishment of the section that was once the shuttle main engine processing facility is complete and will comprise most of the CST-100 capsule process area. The original shuttle processing portion of the building is still undergoing rework. Boeing plans move its Commercial Crew Program headquarters to this building.

John Elbon spoke first, and covered some Boeing history he felt was analogous to the company’s new efforts in commercial space transportation. He spoke not only on the company’s work on the CST-100 for NASA and the need to restore America’s human spaceflight program back to Kennedy Space Center where it belongs, but also mentioned the exciting prospects Boeing sees with Bigelow Aerospace and Space Adventures.

Senator Nelson spoke next. “This is a celebration of a public-private partnership. We are at the dawn of a new era,” he said. He suggested NASA could support more than one company in the next phase of the commercial crew program if it receives the $805 million proposed by the Senate. “That’s enough money for NASA to do the competition for at least two companies, and maybe more,” he said. “That, of course, is up to NASA as they evaluate all the proposals.”

He also addressed concerns regarding the controversy surrounding the RD-180 engine on the Atlas V, which will be the launch vehicle for the CST-100. “The fact is,” Nelson stated, “Roscosmos desperately wants to keep producing those engines. My prediction is that they are not going to stop producing the engines for our missions.” He specifically used “missions”—referring to human spaceflight—as opposed to “payloads”, which would imply military satellites. At the same time, Nelson stated he believed America must pursue a new rocket engine and mentioned significant money has already been set aside to get that work started as part of the defense budget.

John Mulholland also spoke, and mentioned how pivotal it was for the CST-100 program to have Christopher Ferguson as Director of Crew and Mission Systems, and bringing his flight experience on the space shuttle to the CST-100 program. Mulholland actively sought out Ferguson and recruited him to Boeing. Ferguson will be the pilot and commander of the first crewed CST-100 mission, and Mulholland has let Ferguson know that if he does not pick the crewmember for the second seat, his boss would be riding into space on that first crewed mission.

The event featured numerous displays with Boeing engineers willing to discuss progress on various parts and systems of the CST-100 currently going through or have completed development. There were, for example, samples of the heat shield build up and the ablative material that will protect the CST-100 as it re-enters the Earth’s atmosphere at over 27,000 kilometers per hour.

| “That’s enough money for NASA to do the competition for at least two companies, and maybe more,” Sen. Nelson said. “That, of course, is up to NASA as they evaluate all the proposals.” |

The main structure of the capsule is the pressure vessel, as Boeing refers to it, which is being manufactured by Spincraft in Massachusetts. The intricate isogrid machined exterior surface ensures the capsule will be both strong and within the weight limits. Also on display was one of the capsule’s descent parachutes and landing airbags, which will permit the CST-100 to land at White Sands, New Mexico, or any one of a number of alternate sites. This critical design element to avoid ocean landing will allow Boeing’s capsule to be reused for up to ten flights.

Among the most impressive displays was of the Aerojet Rocketdyne Bantam launch abort engine, and the video showing a typical test. To those who remember the relatively leisurely ignition to full thrust of the space shuttle main engines, the immediate full thrust of this engine—complete with shock cones—is truly impressive. Aerojet Rocketdyne completed development testing of this pusher-type launch abort engine in December of last year. Four of these engines, mounted to the Service Module’s thrust structure and each capable of 173,350 newtons of thrust, will separate the CST-100 from the Atlas V in the unlikely event of a launch vehicle failure.

In May of this year, Boeing and Samsung signed an agreement to incorporate mobile technology into the CST-100’s crew and mission operations. “Just as they’ve done on Earth,” Ferguson stated, “mobile tools and devices will enhance the way we operate in space day-to-day, making mission operations more efficient.”

Nowhere is the technological change in human spaceflight more apparent than in the instrumentation and displays of the CST-100 in comparison to the Space Shuttle and even the Apollo capsule. The Boeing capsule will be fully autonomous from the moment of launch to the docking sequence and capture with the International Space Station, and later its return to Earth, much like commercial airliners operate today from takeoff to touchdown.

“The pilot will monitor while the spacecraft does the work,” Ferguson revealed to Frontiers, Boeing’s monthly corporate magazine. “That’s the real big difference between the way Apollo worked and the way we’re working today. The switches in the CST-100 are there to help the crewmember do something quickly. The whole purpose of the instrument console has changed.”

However, each commander of a CST-100 mission will be a pilot astronaut in the classical sense, from the Mercury to the shuttle program. The pilot will be trained to intervene and take control of the capsule at any phase of the mission after separation from the launch vehicle, and will be capable of manually docking the CST-100 to the ISS.

Boeing has achieved every CCiCap milestone to date on schedule, including, this year, the Pilot-in-the-Loop Demonstration, the Spacecraft Primary Structures Critical Design Review (CDR), and Software CDR. The program is on schedule for the Integrated CDR and Phase 2 Spacecraft Safety Review, both scheduled for July.

The exterior of OPF-3, the former shuttle processing building that is being converted into an assembly building for Boeing’s CST-100. (credit: A. Young) |

The Atlas V (HR) and Launch Complex 41

Howard F. Biegler, Human Launch Services Lead for United Launch Alliance (ULA), was on hand to describe the changes that will be made to Launch Complex 41. This chiefly consists of the construction of a crew tower with swing arm that will pivot out to the CST-100 with a crew ingress area at the location of the capsule hatch.

| Boeing and ULA plan for the first CST-100 launch (no crew) early in 2017, with the first crewed mission commanded by Christopher Ferguson to take place mid-2017. |

ULA then took the members of the media out to Launch Complex 41. This pad initially supported the Titan rocket from 1965 to 1977. After being reactivated for nearly a decade, it was reactivated in 1986, operating through the last Titan launch in 1999. It was then reconfigured to launch the Atlas V with the first launch taking place in August 2002. Biegler described the changes that will be necessary to the pad to have the required foundation to support the new Crew Service Tower. Design work on the tower is 96 percent complete, he stated. The tower will have a swing arm much like that used to for access to the Apollo spacecraft atop Saturn rockets. ULA has already worked out the countdown timeline for the crewed Atlas V, the moment the crew enters the capsule, scheduled holds, and final countdown to launch.

Dan Collins, ULA Chief Operating Officer, stated no structural changes to the Atlas V will be required to launch the CST-100 with its Service Module; it will only require a launch vehicle adapter between the CST-100 Service Module and a version of the Centaur upper stage with two RL10 engines. ULA is currently working on the required emergency detection system and a host of related system reviews necessary to achieve the NASA-mandated crew-rating requirements.

Biegler added that the geopolitical issues surrounding the RD-180 engine on the Atlas V used for military payloads have had no bearing on the engine’s availability for commercial crew launches. With respect to the current launch manifest, ULA has engines on hand for 15 Atlas V launches, which typically take place every 60 days. Neither Boeing nor ULA see any RD-180 delivery issues for with respect to its commercial crew activities.

The entire launch vehicle will be assembled within LC-41’s Vertical Integration Facility. The Atlas V core stage is first secured to the mobile launch platform. Two solid rocket boosters will then be mounted to the core stage. The Interstage Adapter is secured to the top of the Atlas V booster, followed by the Centaur upper stage. The Launch Vehicle Adapter is mated next and, finally, the CST-100 with its Service Module completes the stack. Two Trackmobiles move the assembled space launch vehicle on the mobile transporter to the launch pad.

Assuming Boeing does win a contract from NASA to provide launch services for its astronauts and international crew members to the International Space Station, Boeing and ULA state the first launch (no crew) will take place early in 2017, with the first crewed mission commanded by Christopher Ferguson to take place mid-2017. Boeing’s goal is to have the first mission dock to the ISS, not merely make an approach. Human rating the Atlas V also makes possible for Boeing and ULA other human spaceflight missions.

Bigelow Aerospace and Space Adventures

A quote from Boeing’s founder, William Boeing, during the early years of the plane manufacturer, is particularly apropos to the emerging commercial space passenger market: “We are embarked as pioneers upon a new science and industry in which our problems are so new and unusual that it behooves no one to dismiss any novel idea with the statement, ‘It can’t be done.’”

Boeing has been in the commercial passenger jet business since its 707 first took flight in 1958. The company sees this heritage as key to its success in this niche market of taking passengers into space aboard the CST-100. Boeing Space Exploration engineers on the CST-100 program partnered with designers in Boeing’s Commercial Airplanes division in the design of the capsule’s interior. This was a natural and synergistic blending of these two Boeing divisions. This collaboration included everything from the crew seats to the Sky Interior lighting being adapted from the new 737 Sky Interior program.

“We’re going from military-like interiors toward this inflection point of commercial space travel… the next step is to think about the human experience,” explained CST-100 systems engineer Tony Castilleja in Frontiers.

It’s likely there will be differences between the CST-100 interiors used for NASA missions and those used for other commercial flights. This became apparent with the first unveiling of the CST-100 mockup in Las Vegas the end of April. At the same event was Bigelow Aerospace with its full-scale mockup of its BA-330 commercial space habitat. Boeing displayed and made available images to the commercial passenger interior rendered in the unmistakable style of futurist illustrator Syd Mead.

| “We are moving into a truly commercial space market and we have to consider our potential customers—beyond NASA—and what they need in a future commercial spacecraft interior,” Ferguson said. |

Bigelow has been partnering with Boeing on the CST-100 program for several years in the creation of a destination in low-Earth orbit apart from the International Space Station. Bigelow’s efforts are focused initially on commercial business and institution applications of the BA-330 habitat, to be followed by space tourist possibilities.

“We are moving into a truly commercial space market and we have to consider our potential customers—beyond NASA—and what they need in a future commercial spacecraft interior,” Chris Ferguson stated during the event. In the Frontiers article, Ferguson said he desires “…an inviting and comfortable environment for that commercial customer, so they can look back and say that it was a wonderful experience…so they can say, ‘I had the ride of my life.’”

Another partner with Boeing in its commercial space endeavors is Space Adventures. The company has ambitious plans of taking its paying passengers aboard the CST-100 to low Earth orbit and perhaps even beyond.

“We’ve got a great relationship with Space Adventures,” John Mulholland told Space News in November of 2012. “I love the idea of flying people up to the International Space Station. It brings additional awareness to all the good things that are being done on the space station. You build advocacy. So we really hope to be able to partner with Space Adventures and NASA to fly customers in extra seats to the International Space Station.”

Who will the winner(s) be?

In all the conversations I had with Boeing and ULA executives, managers, and engineers, there was a palpable confidence that their companies will be building the next American crewed spaceflight launch vehicle and spacecraft and restore to this country its human spaceflight program.

At the same time, they all expressed caution, saying they are awaiting NASA’s decision, probably in August, for the selected companies to proceed to the next phase, which is the Commercial Crew Transportation Capability (CCtCap) award. Kathy Lueders, the commercial crew program manager at NASA, embraces the belief that competition is the best means of achieving its goals of crew safety, advancing technology, and innovation at a favorable cost while preventing dependence on a single provider.

Decisions NASA previously made on commercial cargo contracts to SpaceX and Orbital Sciences may give an hint as to how many companies NASA plans to support with CCtCap awards. It is the unspoken belief at Boeing and ULA that Launch Complex 41 will become the departure point of America’s next phase in human spaceflight.