All alone in the nightThe Manned Orbiting Laboratory emerges from the shadowsby Dwayne A. Day

|

| For many people, including the group of MOL astronauts who had been training to fly the spacecraft and operate its sophisticated, powerful KH-10 optics system, the cancellation came as a surprise and a shock. |

What they did not realize was that MOL had been in battle and was deeply wounded. At the very senior levels of the intelligence community, the people who were cleared to know about all of MOL’s secrets knew that the program had come under increasing criticism in recent years about its purpose and its cost, and about the wisdom of flying astronauts on a reconnaissance spacecraft where their presence added much complexity and very little benefit.

In early 1969, President Nixon had canceled the HEXAGON reconnaissance satellite program. HEXAGON was MOL’s rival in terms of funding. Both spacecraft used large Titan III launch vehicles, cost a lot of money, and had fallen behind schedule. But HEXAGON and MOL had very different purposes. HEXAGON was equipped with cameras that could spot objects smaller than two feet (0.6 meters) on the ground, but could also photograph thousands of square kilometers at a time, gathering a staggering amount of information on the status of Soviet strategic and tactical forces in a single mission. MOL, with its big KH-10 camera system, focused on tiny areas at very high resolution, and could have spotted a softball dropped on a parking lot. The MOL concept was that two Air Force astronauts would look through the viewfinder and if they saw something interesting, like a Soviet X-plane on an airfield, they would press a shutter button and take a picture. The overall reconnaissance mission, including the collection of signals intelligence, was code-named DORIAN.

MOL was an Air Force program—with the NRO responsible for DORIAN—whereas HEXAGON was CIA, and soon after HEXAGON’s cancellation the Director of Central Intelligence Richard Helms made a plea to Nixon to reverse the decision, arguing that HEXAGON was vital for understanding what the Soviet Union was doing, and MOL was not. Anybody who did not know about MOL’s reconnaissance mission, or the HEXAGON program, was completely in the dark about this super-secret struggle, and even those who were aware of parts of the story didn’t know what the upper-level bosses were doing.

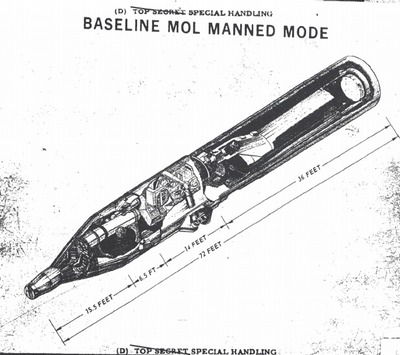

A recently-declassified illustration released by the National Reconnaissance Office shows the Manned Orbiting Laboratory in its crewed configuration. |

The details about this fight, and about MOL’s design and especially its highly classified DORIAN mission have only come to light in the past few years. Two years ago the National Reconnaissance Office released the first drawing showing MOL’s internal configuration. It depicted a Gemini spacecraft at the front, a pressurized cabin for the astronauts at the middle, and a big unpressurized compartment holding a folded optics system that bent light into the spacecraft, reflected it off a 1.83-meter (72-inch) primary mirror, and then sent it forward to a few more mirrors that directed it into the astronauts’ work compartment.

In addition to the drawing, the National Reconnaissance Office released some programmatic details about MOL, particularly about its clash with HEXAGON. That information essentially confirmed the account in Jeffrey Richelson’s 2001 book The Wizards of Langley.

| Even if MOL’s supporters could justify the high resolution requirement, there was another question about MOL: if MOL could do its mission without astronauts, why were they necessary? |

Now, in response to a Freedom of Information Act request by Joe Page, the NRO has released more illustrations of MOL. Some of the images are grainy photocopies, but they provide a better view of the interior of the spacecraft than has been released before, including a good illustration of the folded optical system that used a reflecting mirror to direct light into the camera and could rotate back and forth to provide images of targets at different angles as the spacecraft passed overhead.

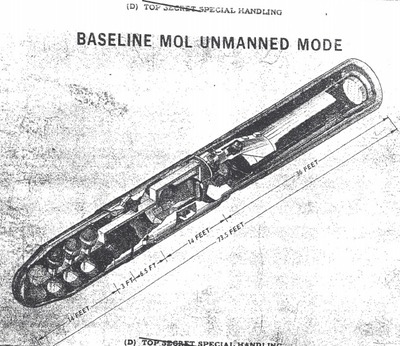

Over the past decade, information on MOL has come out from various sources. In 2004, an Aerospace Corporation article appearing in their in-house magazine indicated that MOL had also been designed to operate without a crew. In 2012, the NRO released a 1965 drawing that showed a preliminary concept of this “Unmanned MOL.” Now a more detailed drawing of the “Baseline MOL Unmanned Mode” has been released, showing far more detail, including what appears to be up to twelve satellite recovery vehicles (SRVs) used to return film to Earth.

A photo showing MOL hardware under construction. |

One of MOL’s biggest problems was that it was always a rather expensive way to accomplish a requirement that many people did not think was valid: extremely high resolution. That high resolution came with a price: very small image areas. Years ago a retired intelligence officer described attending a MOL briefing at the Washington Navy Yard, probably in 1967 or 1968. He accompanied Director of Central Intelligence Helms and Vice President Hubert Humphrey. During the briefing about MOL’s big KH-10 camera, Helms wrote something on a small piece of paper, folded it, and slid it over to Humphrey. Humphrey looked at it, refolded it, and slid it back to Helms. When the briefing ended and everybody got up and left, the intelligence officer hung back and grabbed the piece of paper. He opened it and noticed that Helms had written a question for the vice president to ask the person doing the briefing: “Why four inches?” That was DORIAN’s resolution, and the CIA’s reconnaissance experts believed that there was no valid justification for such a powerful reconnaissance system, especially at such high cost. Humphrey had never asked the question, but certainly the CIA reconnaissance experts kept asking that question again and again.

Even if MOL’s supporters could justify the high resolution requirement, there was another question about MOL: if MOL could do its mission without astronauts, why were they necessary? They were certainly expensive, and deleting them and their Gemini spacecraft could save a lot of money. But even that question begat another: would an unmanned MOL, with twelve reentry vehicles, provide more and better capability than six GAMBIT-3 reconnaissance satellites, each launched separately and equipped with two reentry vehicles and a KH-8 camera that was almost as good as the KH-10? By 1969 the GAMBIT-3 was fully proven and in production, whereas MOL was still several years from flight, and a single unmanned MOL launch failure, or an electrical or mechanical failure in flight, could wipe out a lot of capability and leave the intelligence community blind.

A photo showing MOL hardware under construction. |

There are still many unanswered questions about MOL, including exactly how it would work and how the astronauts would operate it. There are also many details to be explained about the MOL program’s schedule, such as whether the Air Force and NRO would conduct a test mission first before attempting to make the system operational. The nominal MOL mission was thirty days, far more than any American crew had spent in space up to that time, and requiring a lot of additional human factors learning that ultimately did not occur until Skylab in 1973.

But it is clear now that the answers are emerging, and each is generating many spinoff questions. Forty-five years after its cancellation, MOL is finally starting to give up its secrets.