India and the satellite launch marketby Ajey Lele

|

| Now the time has come to move beyond projections and wishful thinking and put in context India’s position in this sector. |

For the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), the success of this launch is yet another confirmation of the robustness and reliability of its PSLV system. This was the 26th consecutive successful flight (out of a total of 27 flights) of PSLV. The previous all-commercial mission for ISRO was the September 2012 launch of the SPOT-6 satellite for France along with a 15-kilogram Japanese satellite on mission PSLV-C21. The lift-off mass of SPOT-6 was 712 kilograms, the heaviest satellite to be launched by ISRO for an international customer until SPOT-7.

During the last couple of years, ISRO has won international attention with several successful non-commercial and commercial launches by its reliable workhorse, the PSLV. Also, ISRO has effectively showcased its capabilities to the rest of the world by succeeding with its Moon and Mars programs, the latter still en route to Mars. On the commercial front, ISRO is now offering reliable and economical space products and services to various international customers.

During the last few years India has shown an interest in entering the global commercial satellite launch market. The growing aspirations and needs of various smaller nations in the 21st century to operate and make use of space systems provide opportunities for India to expand its commercial base, as do the needs of various European, Asian, and Latin American nations. Some reports predict a minimum growth of 15% in the commercial launch market segment over the next few years. All this indicates that, apart from the established satellite launching agencies, these customers could look for newer and cheaper options for launching their satellites.

There are some unconfirmed reports suggesting that that India provides launch services at about 75% of the price charged by other agencies. Naturally, India could expect a great future for itself in this field and the success of PSLV-C23 could be viewed as an initiation of this process. However, now the time has come to move beyond projections and wishful thinking and put in context India’s position in this sector within the backdrop of global realities.

As the latest “State of the Satellite Industry” report published by the Satellite Industry Association notes, overall satellite industry revenue was US$195.2 billion in 2013 and US$188.8 billion during 2012. In general, during last five years the overall growth rate of satellite industry as a whole has been varying approximately between 5 to 15%. However, there have been greater variations, including some decreases, in the revenue for the satellite launch sector, as the following table illustrates:

| Year | Revenue in US$ billions | Growth Rate in % |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 3.9 | 21 |

| 2009 | 4.5 | 17 |

| 2010 | 4.4 | -2 |

| 2011 | 4.8 | 9 |

| 2012 | 5.8 | 21 |

| 2013 | 5.4 | -7 |

The growth rate was negative in 2010 owing to the decrease in the US satellite launch industry revenue but, in 2013, it was the non-US part of the industry that caused the decrease. However, statistics always do not present an absolute view. At times the actual statistics does get affected by minor variations like changes in launch schedules, reduction in number of launches, and so on.

| India has significant ground to cover if it wants to compete with other launch providers. |

Broadly, the half of the commercial satellite launch market constitutes of low earth orbit (LEO) launches and most of the rest consists of launches into geostationary orbit (GEO). Mostly, the contracts for more than half of the total launch market are grabbed by European providers and rest gets divided amongst others, primarily from Russia and the US. China gets around 2 to 3% of these contracts.

Presently, Arianespace of France (founded in 1980, world's first commercial space transportation company) is a leader in Asia-Pacific region with 64% of the launch market. They have an impressive order book and are expected to launch more than 30 satellites in near future for more than 25 customers. It is also important to note that the core launch market for present and future would constitute of launching telecommunications satellites (weighing 3 to 7 tonnes) to GEO.

India needs to factor in all these realities to plan their business model. In comparison with the major US, European, and Russian providers, India is just a beginner in satellite launch business.

Prior to Monday’s launch, India had launched 35 satellites for various other countries. Some of these launches were based on commercial agreements while some were under bilateral government-to-government arrangements. All these launches were made by the PSLV, indicating that most of these launches were for satellites in LEO. The classification of these 35 satellites by mass is shown in the table below:

| Satellite Category | Number |

|---|---|

| 1–10 kg (nano) | 18 |

| 11–100 kg (micro) | 9 |

| 101–500 kg (mini) | 7 |

| 501–1000 kg | 1 |

The total mass for all 35 satellites is just 2355.2 kilograms. This indicates that assessing India’s capabilities based only on number of satellites launched would be incorrect. Presently, India has significant ground to cover if it wants to compete with other launch providers. India needs to address the following crucial challenges and undertake some intelligent planning:

Launch Vehicles: In January, ISRO successfully launched a nearly two-tonne satellite using its Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV-D5). The importance of this launch was that it was powered by an indigenous cryogenic engine (see “GSLV-D5 success: A major ‘booster’ to India’s space program”, The Space Review, January 6, 2014). It was a result of more than a decade’s efforts. This launch could be viewed as a step towards consolidating capabilities for launching heavy satellites to GEO.

However, in order to compete with Arianespace and other providers and enter the GEO satellite launch market, India needs to quickly operationalize its GSLV system, which is capable of launching satellites weighing 4 to 6 tonnes. It is also essential for India to develop semi-cryogenic engine technology to establish itself in the arena of launching of heavy satellites. As a short-term measure, India needs to concentrate towards attracting maximum “PSLV-capable” business.

Business Model: It is important to appreciate that ISRO is a research organization and business is not its main mandate. For last few decades, the commercial arm of ISRO, called Antrix Corporation, has been responsible for various commercial activities, and did approximately US$240 million worth of business in 2013. Recently, Antrix has signed agreements with British and Singaporean organizations to launch their spacecrafts on PSLV missions in 2014 or 2015. DMC International Imaging, a subsidiary of Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd. in the UK, plans to use the PSLV to launch their three 350-kilogram disaster monitoring satellites. ST Electronics (Satcom and Sensor Systems) Pte. Ltd. of Singapore has a contract ISRO to launch its 400-kilogram TeLEOS-1 earth observation satellite. Antrix has also bagged a contract to launch an 800-kilogram German satellite, called Environmental Mapping and Analysis Program, or EnMAP.

Antrix is mainly an administrative agency and ISRO is required to provide the entire technical support to undertake any commercial launches. Presently, ISRO’s research and development work is suffering because of its business commitments. Globally, various launch providers are private bodies and supported by governmental agencies. It is essential for ISRO to engage private organizayions and transfer the launcher technology to them to expand business interests. ISRO has already initiated this process and expects that it would take three to four more years to evolve a commercial launch system.

| As a short-term measure, India needs to concentrate towards attracting maximum “PSLV-capable” business. |

This opportunity should be used by India to create thriving space industry, rather than to get complacent by only developing a private PSLV launch provider. ISRO can learn a lot from India’s experiences in developing its own defense industry. For many years India could not develop a private defense industry architecture for various reasons, primarily the lack of clarity in policies. For the space sector, there is a need for India to evolve specific policy guidelines and improve on existing procedures to remain in tune with the existing and future space business ecosystem. The government should provide all the necessary help to promote this business sector. It is important to appreciate that the “gestation period” for the development of this sector will be much longer than various other industries, and hence there is a need for the government to make a long-term commitment. It will be also important to allow Indian providers to bid for global contracts.

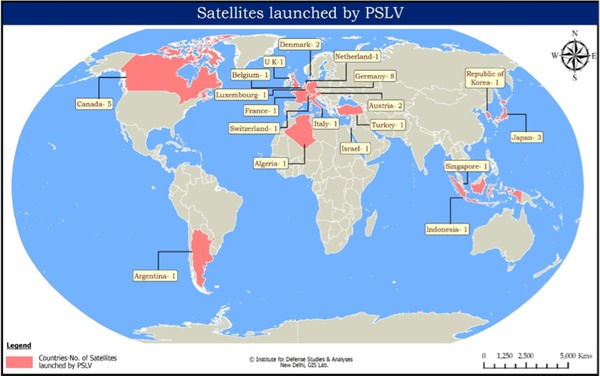

Launch Clients: The diagram below provides a broad idea about India’s client base for launch services:

|

It is evident that, so far, India’s client base has been primarily European nations and Canada. It is surprising that none of India’s neighboring states are using India to launch their satellites. It is important to mention that nations such as Sri Lanka have recently chosen China as an option for space collaboration, while Afghanistan has procured a satellite from European providers. Along with South Asia, India needs to expand its customer base to regions like Latin America, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia.

India has been part of various multilateral arrangements and associated with some others, like South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC); India-Brazil-South Africa (IBSA); Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS); Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum; and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). There is a need to use such forums effectively to attract space business.

Launch Sites: Over the years India has been able to perform two to four launches per year. By comparison, nations such as the US, Russia, and China often conduct 20 or more launches per year. Obviously, to gain ground in the commercial launch market India needs to significantly enhance its launching capabilities.

ISRO has one site for satellite launches, at Sriharikota (13°N, 80°E) in the southern part of India. It has two operational launching pads, and a proposal for developing a third pad is under consideration. There have been some recent proposals to develop Tuticorin district (8°N, 78°E) as a new launch site. The geographical position of this place is more favorable for launches and could help increase launch vehicle performance.

During the 12th five-year plan period (2012–2017), ISRO has planned 58 missions. Any further addition to these missions, in order to meet additional commercial demand, would require improvement in ground infrastructure. ISRO is already undertaking a detailed cost-benefit analysis regarding a second launch site, which should include the likely needs of private industries. There is also the possibility that ISRO could develop (or upgrade the existing sites) any additional launching sites in other nations, such as Brazil or Indonesia.

Legal Norms: Various space activities have political and legal risks apart from the obvious technical risks. Normally, national policies in fields like missiles and nuclear technology do affect the nature of international collaboration. At times, technical capabilities alone are not sufficient to widen the customer base and various issues related to compensation obligations, liability laws, and export control mechanisms affect commercial interests.

| The success of PSLV-C23 offers India the opportunity to demonstrate the PSLV as a reliable and low-cost vehicle with wider utility for commercial purposes. |

China performs around 20 launches per year and most of those launches are for domestic uses. Their present share of the worldwide commercial launch market is around 2–3%. This indicates that, in spite of having technical capabilities and required infrastructure, they are not able to enhance their market share primarily because of various political and legal hurdles, as well as issues related to intellectual property protection.

It is important for the Indian state to ensure that export compliance issues and other related political and legal issues are addressed in a timely fashion to ensure that Indian industry does not get caught into any legal tangles.

The success of PSLV-C23 offers India the opportunity to demonstrate the PSLV as a reliable and low-cost vehicle with wider utility for commercial purposes. Over the next three to four years, India needs to fully commercialize its PSLV services. In the short term, India needs to concentrate towards developing various business-related capabilities for launching of satellites weighting two tonnes or less. In the long term, the success of Indian providers in the commercial satellite launch market will depend on how quickly India can mature its GSLV program for launching heavier satellites into GEO.