Witnesses: Space historiography at the handover (part 1)by David Clow

|

| Memories change, and hyperbole and mythification in the historiography of flight started before Kitty Hawk, but today the opportunities and incentives to bend the facts are much greater. |

Apollo 15’s Dave Scott observed something both remarkable and widely overlooked about how fortunate we were: since ancient times people had envisioned a lunar landing, but no one anticipated that people on Earth would see it as it happened.1 Those of us who watched the race to the Moon had the additional rare privilege of understanding it in the context of history. We could be witnesses who knew what happened, but also what it meant. Later, as space historians, we could tap vast records, see the places where it happened, and best of all, talk with the people who made Apollo a reality. In payment for our good fortune, our obligation as historians is to keep the record straight. That challenge might appear easier than it really is.

Turbulence in time

Almost 85 years ago, Carl L. Becker, then President of the American Historical Association, warned that distortion in the historical record was a generational inevitability. “However accurately we may determine the ‘facts’ of history,” he said, “the facts themselves and our interpretations of them, and our interpretation of our own interpretations, will be seen in a different perspective or a less vivid light as mankind moves into the unknown future.”2

Memories change, and hyperbole and mythification in the historiography of flight started before Kitty Hawk, but today the opportunities and incentives to bend the facts are much greater than they were when Becker addressed his colleagues. The speed of communications, the insatiability of the old and new media, and the number of people seeking to contribute to the conversation in space history (especially as we approach the 50th anniversaries of the lunar landings) all invite the substitution of true-seeming “facts” for actual facts. The danger to the record is that when enough distortion and hype have crept into the documentation, verisimilitude might look so much like authenticity that people who need the facts get only “facts,” and they cannot tell the difference.

In 1969, despite (or because of) 600 million observers seeing Apollo 11, the facts got tangled and the details blurred in a huge version of the children’s game “Telephone.” Forty-five years later, millions of people who were here for it, people who could follow flights from launch to splashdown, seem to see it mythologized through a blizzard of ticker-tape. Others, like Dr. Walter McDougall, who won the Pulitzer Prize for The Heavens and the Earth: A Political History of the Space Age, see it more accurately, but feel “a mood of disappointment, frustration, impatience over the failure of the human race to achieve much more than the minimum extrapolations made back in the 1950s, and considerably less than the buoyant expectations expressed as late as the 1970s.”3 And of course, millions more insist that it never happened at all.4

“You had to be there” is the shorthand way of expressing the phenomenon of blurring memory, and as space exploration began, in a colossal fluke, we really were there. Here at the handover, we are the historians and enthusiasts who inherit the task of keeping the record. How we perform will say a great deal about us both as curators and as people. Future generations will judge us on how well we understood how lucky we were to be here at our Kitty Hawk.

Mission Control served then to say what to do, and it might serve again as a model for how space historians can proceed.

Keeping true

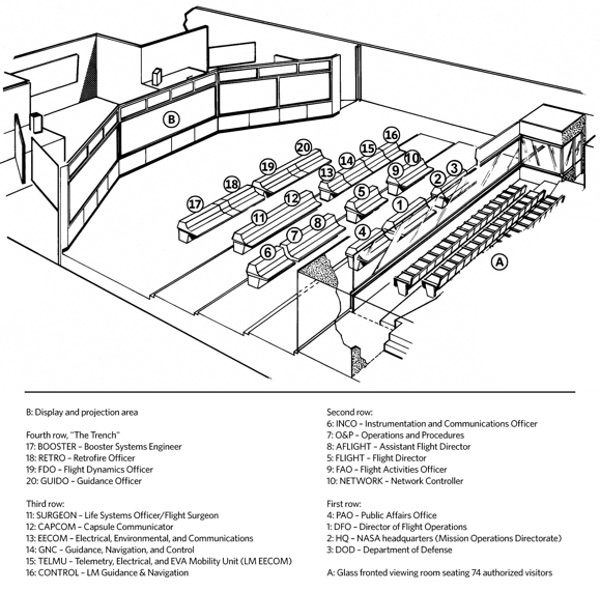

The Apollo Mission Operations Control Room (MOCR) at Johnson Space Center was a room designed for historians, and for the recording of history, as the illustration below shows.5

The Apollo Mission Operations Control Room at what is now the Johnson Space Center. |

Obviously, historiography as practiced in the MOCR is different from the way one usually thinks of it. The texture of time, so to speak, is thicker there; the fabric of history is woven fast and tight in threads of seconds. That said, the objectives are the same for flight controllers who worked moment by moment as they were for historians chronicling eras: to know what happened, to weigh its interpretations, and to advise the next users, whether those users were coming on-shift in an hour or a thousand years in the future. Like a spaceflight, history has a trajectory. In both, a slight inaccuracy here and now can corrupt the text, introduce mistakes, and have serious effects further along the path.

| Like a spaceflight, history has a trajectory. In both, a slight inaccuracy here and now can corrupt the text, introduce mistakes, and have serious effects further along the path. |

Yes, something similar could be said about plenty of decidedly unhistoric occupations. A developer writing code for the videogame “Grand Theft Auto” today is paid to get it right, obviously, because sooner or later his errors will compromise the product. However, we can credit Mission Control with aspiring to more than just technical competence. A deeper level of excellence was called for, one that had roots in Virginia and Florida before the Manned Spacecraft Center was on the drawing board, as Flight Director Gene Kranz recalled:

The Space Task Group was an incredible organization composed of three different cultures… classical aeronautical engineers from Langley Research Center, experienced mid-level engineers from the Avro Arrow flight test and engineering team, and young college engineers from America’s universities.

The “chemistry” created by these three elements created an organization that was greater than the sum of its individual members. The leadership skill of Dr. Robert Gilruth and Walt Williams was what empowered Mathews, Kraft, Faget, Chamberlain and others to develop and achieve their inborn potential and thus build incredibly potent teams.6

The Culture of Mission Control was born at the Cape… amid the sand, raw asphalt, salt grass, cement block buildings and antennas. There the foundations of leadership, trust, values and teamwork formed.7,

Dr. Christopher C. “Chris” Kraft Jr. pioneered the technical and logistical procedures that made Mission Control work, but the foundation of his achievement was the ethos of integrity and mutual accountability that Kraft created for it.8

Kraft also set the tone for one of the most striking features of Flight Operations, unquestioning trust—not of superiors by subordinates, but the other way around. In the flight control business, where the consequences of mistakes could be irretrievable, this level of trust was sometimes an awesome thing to receive.9

That trust was given freely, which was extraordinary considering how new all this was; the people who committed themselves to it relied on their innate skills and character to offset the unknowns that lay in wait for them. The ambiguities were vast, so the charge was simple: do it right. (Gene Kranz emphasizes that “A flight director’s got probably the most interesting job description in history. It's only one sentence long: ‘A flight director may take any action necessary for crew safety and mission success.’ That's it.”10 Kranz was 31 when he took the job. Glynn Lunney was 28.11 In his review of this article, Kranz asked specifically that the job description be included verbatim.) Kraft made hires with startling speed to build his new team.12 He demanded competence, of course, but the fundamental standard they had to meet was not perfection. It was honesty, and it was tested under intense pressure.

Gerald D. “Gerry” Griffin served as Flight Controller, Flight Director, and Director of the Johnson Space Center, all after initially turning NASA down. He interviewed for a position with Gene Kranz in 1962, but took a job with a defense contractor when NASA’s offer was too low. Two years later, though, he recalled, “I wanted to get [to Mission Control] so bad that… I swallowed my pride and my wallet and came to work in Houston.”13 He wanted to be part of history that was woven so rapidly. It was the newness and the speed of it that Griffin found irresistible: “[N]obody had actually been in that pressure cooker, split-second, decision-making on the ground,” he remembered. “Plenty of guys had been in airplanes doing that, but there [were] not many people that had done it from a ground standpoint, where it had to be an instantaneous kind of thing.”14

That “instantaneous kind of thing” required absolute integrity. You could be incorrect; you could say so and adjust; but lying in any form was the thing that Kraft never tolerated. “Sandbagging,” bluffing, obfuscating, withholding what you knew; those were breaches of trust that ended careers, sometimes on the spot, because your lie or bluff would be trusted, woven into history that moment, and so it would threaten the mission. If you needed data to do your job, and someone at another console forgot or hesitated to provide it, things could get heated.15 That pursuit of fact had to be standard practice at every console.

Jerry Bostick earned his place among the flight controllers early in the Gemini program.

It was during Network Simulation number 1 (NS-1), which was a test of the tracking network, the Control Center, and Gemini Mission Rules. I’d been in the Mission Planning division and my boss there was Carl R. Huss [from the Mission Planning and Analysis Division, NASA Manned Spacecraft Center. ]16 I had been to the Cape to support him from the back room for Mercury-Atlas 8 and 9. At the end of Mercury, Carl had a heart attack, and they asked me to step in for him. I still had to go through the sim[ulation]s. I felt like I was on trial whether I was or not.

The first time I was asked to participate in NS-1 and try out as a flight controller, there were a couple of others with me, and as I did, the other two guys also made a mistake in the sim. I really made a bad one—I called for a launch abort and I shouldn’t have. The other two guys tried to make excuses, talk their way out of it, and when it got around to me, I said, “I screwed up. I read the wrong line. I aborted and that’s a serious thing, I shouldn’t have done it and I guarantee it won’t ever happen again.” The other two guys went back home, and Chris Kraft allowed me to stay. There were others—I won’t name names—who were flight controllers in Mercury that made some errors in actual missions and tried to talk their way out of it, and they were not asked to ever be a flight controller again.17

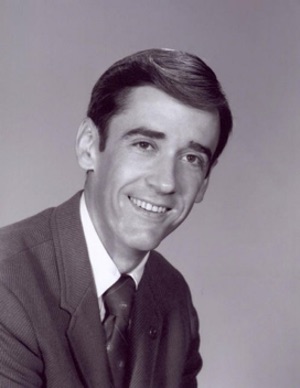

Jerry Bostick (NASA) |

| “Sandbagging,” bluffing, obfuscating, withholding what you knew; those were breaches of trust that ended careers, sometimes on the spot, because your lie or bluff would be trusted, woven into history that moment, and so it would threaten the mission. |

Note that this test was a simulation, not an actual mission. Even in an inauthentic situation, an inauthentic answer was forbidden. It made for rigorous self-examination and peer review. “Usually, with the exception of Apollo 13, the sims were much harder than the missions,” Bostick remembers.18 They had to be conducted as though lives really were on the line. The simulation supervisors (SimSups) took pains to make the scenarios challenging, and the post-sim reviews—the MOCR’s study of its own history—were unforgiving. As Bostick recalls, “the debriefings sometimes could get very bloody. I mean, you know, ‘Why didn't you catch that?’ or, ‘Well, you know, it wasn't my responsibility,’ or, ‘Why didn't you take action quicker?’ Or the sim guys would say, ‘Well, I gave you this failure and you didn't even see it.’"19 Lunney corroborated that the inquisitions were the rule, not the exception: “The simulations we used to run, oh, woe be to him who screwed up!” he said:

[W]e debriefed each simulation, and it was confession time. It was absolute confession time. Whatever happened, you had to recount what happened, what you saw, what you did, and why. And, occasionally people would do something that was a little bit not correct or incorrect, as seen in retrospect, and they would suffer the humiliation of exposing themselves and maybe even getting some chewing on for whatever they did that wasn’t quite right.20

The endless reviews sharpened everyone’s technical competence, but the unspoken agenda was the primary one: to assess the quality of the people at the consoles. By liftoff, anyone who still failed to appreciate the distinction between verisimilitude and authenticity had been marked as a liability.21 “As far as ‘bluffing in the MOCR’, I don’t recall it ever happening during a mission,” Bostick recalled. “By then, all the bluffers had been weeded out in the simulations.”22

| The endless reviews sharpened everyone’s technical competence, but the unspoken agenda was the primary one: to assess the quality of the people at the consoles. |

Kraft’s historians thrived on the culture of integrity under pressure. They could be jawing nose-to-nose on shift and later use the same profanities telling jokes over beer in personalized squadron mugs at the Singing Wheel. The young men like Griffin who wanted it understood the commitment they were making, and the sacrifices it would require. (Sy Liebergot called Mission Control the “new mistress.” )23 Kraft was the paradigm. He was inspiring, intimidating, a man with “an uncanny knack for doing the right thing,”24 whose integrity set the true course for everyone in Mission Control. The path was personal: if you wanted to make a career of making history, you had to write a personal life story of resiliency, character and integrity, understated and terse, without hyperbole and mythification. If you lacked that peculiar blend of stoicism and passion, you got weeded out.

Gene Kranz on building the MOCR team

Gene Kranz offered a different view of the dismissal of flight controllers as follows:

A general theme in your article is that Kraft often removed controllers directly for performance as a result of performance in simulations… To my knowledge this only happened twice… once during Mercury and another time with [name redacted] in Gemini. Statements like those in your article have become common lore in recent books and articles when controllers were speaking of Kraft in Mission Control and of our culture.

I handled the controller terminations for Mercury. Kraft replaced only one controller after a mission because he could not make up his mind and Kraft had to make the unilateral decision to terminate the mission. As noted in my book, the Original Mercury Control teams were “draftees” from the engineering organizations…. We started bringing in experienced personnel from the remote sites starting with MA-6, [Glynn] Lunney and [John] Llewellyn and [Arnold] Aldrich for MA-7. From then on we began the development of operations professionals in Mission Control.

During Gemini my Branches provided all systems controllers and I terminated [name redacted] for disciplinary purposes, not technical issues. During Apollo I was Division Chief for Flight Control, the console manning was virtually unchanged throughout the entire program… I know of no terminations. Kraft frankly was too busy with getting Apollo… he trusted his flight directors to build competent teams.

During simulations the Branch Chiefs, SimSup and Flight Director monitored controller performance. The Branch Chiefs were the ones who initiated the actions to retrain or remove. Often the Branch Chiefs would establish a mentor if a controller was having problems. Performance problems during simulations normally occasioned a one-on-one between a controller in the office and their respective supervisor.

Simulation Performance and Utilization - Simulation time was a precious resource. Virtually all of the controllers who were unsuited for operations were “weeded out” by the Branch Chiefs prior to simulation start. When a controller was assigned a console position he was certified by his section and branch chief as having technical knowledge for the job. The Simulation purpose was to (1) integrate the flight control team (2) integrate the Flight control team with the Crew (3) Validate mission planning and documentation (4) Validate configuration integrity of MCC and Network. SimSup was very adept at finding holes in the controller-controller interface and forcing ambiguous time-critical decisions. After the Apollo 1 fire Kraft moved to address the challenge of the Apollo Program and left the Flight Director responsibilities to his protégées. I became the Deputy Chief to [John] Hodge for Flight Control and then Chief in 1969. This included the Flight Director Office, which I assigned to Lunney.25

Endnotes

- Scott said, “Of all the science fiction writers who ever wrote about going to the moon, I don’t believe any of them ever dreamed about the world watching it on television.” David Sington, et al. In the Shadow of the Moon. Discovery Films, FilmFour, Passion Pictures. 2007.

- Carl L. Becker, “Annual address of the president of the American Historical Association, delivered at Minneapolis, December 29, 1931.” From the American Historical Review 37, no. 2, p. 221–36. http://www.historians.org/about-aha-and-membership/aha-history-and-archives/presidential-addresses/carl-l-becker. Accessed May 15, 2014.

- Walter A. McDougall, “A Melancholic Space Age Anniversary.” In Steven J. Dick, Editor. Remembering the Space Age. Proceedings of the 50th Anniversary Conference. National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of External Relations History Division Washington, DC. 2008 NASA SP-2008-4703. http://www.nss.org/resources/library/spacepolicy/Remembering_the_Space_Age.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2014. p. 403.

- Brandon Griggs. “Could moon landings have been faked? Some still think so.” CNN. Fri July 17, 2009. http://www.cnn.com/2009/TECH/space/07/17/moon.landing.hoax/index.html. Accessed May 23, 2014.

- NASA/Aurich Lawson. Lee Hutchinson, “Apollo Flight Controller 101: Every console explained.” Ars Technica. Oct 31 2012. http://arstechnica.com/science/2012/10/apollo-flight-controller-101-every-console-explained/. Accessed June 20, 2014.

- Robert Gilruth (1913–2000), Assistant Director at Langley Research Center from 1952 to 1959, Assistant Director (manned satellites) and head of Project Mercury from 1959 to 1961. In early 1961, T. Keith Glennan established an independent Space Task Group (already the group's name as an independent subdivision of the Goddard center) under Gilruth at Langley to supervise the Mercury program. Moved to the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), Houston, Texas, in 1962. Gilruth was the Director of the Center from 1962 to 1972. (http://history.nasa.gov/naca/bio.html; accessed July 23, 2014).

Walter C. Williams (1919–1995) Assigned responsibility for overall launch operations in Project Mercury in 1959. Directed the Worldwide Tracking Network and recovery operations for manned space flight missions. As Operations Director in Mercury Control Center at Cape Canaveral, Florida, performed as Flight Operations Director for MR-3, MR-4, and MA-6; Deputy Associate Administrator in the Office of Manned Space Flight at NASA Headquarters, NASA Chief Engineer. (http://www.nasa.gov/centers/armstrong/multimedia/imagegallery/Directors/index.html#lowerAccordion-set1-slide10; accessed July 23, 2014).

Dr. Maxime A. Faget (1921–2004), Director of Engineering and Development at the Manned Spacecraft Center for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in Houston, Texas starting February 1962. Responsible for technical support of the Gemini and Apollo manned space flight programs and advanced studies into space systems. Served on the Steering Committee which helped the NASA Administrator make Project Mercury policy decisions. (http://history.nasa.gov/Apollo204/faget.html; accessed July 23, 2014).

James Arthur Chamberlin (1915–1981). Canadian aerodynamicist recruited in 1959 with a group of engineers from Avro Canada for the Space Task Group. Head of engineering for Project Mercury; project manager for Mercury manufacturing processes and troubleshooting. Gemini¹s first Program Manager. Made many direct contributions to the success of Apollo, including advocacy for lunar orbit rendezvous. (http://www.history.nasa.gov/chamberlin.html; accessed July 23, 2014).

Charles W. Mathews (1921–2001) NASA Associate Administrator for Applications from 1971 until 1976. B.S. in Aerospace Engineering from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in 1943, joined the engineering staff at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics Langley Research Center. Conducted research on supersonic flight, automatic control devices and systems for use in the interception of enemy bombers, and piloted spacecraft studies. In 1958, became chief of the NASA Space Task Group Operations Division and was responsible for the overall operations of Project Mercury. Named Gemini Program Manager at the Manned Spacecraft Center in 1963. Director of the Skylab Program in 1966 l in 1968, named Deputy Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight. (http://history.nasa.gov/biosk-n.html#M; accessed July 23, 2014) - Personal email to the author from Gene Kranz, July 5, 2014.

- Chris Kraft, Flight: My Life in Mission Control. New York: Dutton. 2001. p. 89.

- Charles Murray and Catherine Bly Cox. Apollo. The Race to the Moon. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1989. p. 284

- NASA History Portal, “December: A Significant Month in Apollo.” http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/special_events/Apollo_Dec.htm. Accessed July 21, 2014.

- Charles Murray and Catherine Bly Cox. Apollo. The Race to the Moon. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1989. p. 287.

- “So Kraft looked at me and he said, ‘You're a civil engineer?’

‘Yes.’

‘What do you do?’ I told him. He said, ‘Why do you want to join us and go to Houston?’

I said, ‘Well, I really would prefer to work on real problems, finding solutions to real problems rather than just doing pure research. Unfortunately, it's taken me a couple of months to figure that out, and I just would much prefer to work on the manned space program.’

So he turned about to [Chris C.] Critzos and he says, ‘Hell, hire him. We might need somebody to survey the Moon.’”

Jerry C. Bostick, Interviewed by Carol Butler. NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Edited Oral History Transcript. Marble Falls, Texas – 23 February 2000. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/BostickJC/BostickJC_2-23-00.htm. Accessed May 26, 2014. - Gerald D. Griffin, Interviewed by Doug Ward. NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Edited Oral History Transcript. Houston, Texas – 12 March 1999. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/GriffinGD/GriffinGD_3-12-99.htm. Accessed June 7, 2014.

- Gerald D. Griffin, Interviewed by Doug Ward. NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Edited Oral History Transcript. Houston, Texas – 12 March 1999. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/GriffinGD/GriffinGD_3-12-99.htm. Accessed June 7, 2014.

- Sy Liebergot, interview with the author, June 9, 2014. The point of being a Flight Controller was having control. Liebergot was appalled when NASA dropped the term and called them “Operators.” Sy Liebergot with David M. Hartland. Apollo EECOM: Journey of a Lifetime. Burlington, Ontario, Canada: Apogee Books: 2003. p.121.

- NASA History Office SP-45. MERCURY PROJECT SUMMARY INCLUDING RESULTS OF THE FOURTH MANNED ORBITAL FLIGHT. MAY 14 AND 16, 1963. October 1963. Office of Scientific and Technical Information. NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION. Washington, D.C. http://history.nasa.gov/SP-45/cover.htm

- Interview by the author with Jerry Bostick. May 14, 2014

- Interview by the author with Jerry Bostick. May 14, 2014.

- Carol Butler, “Interview with Jerry C. Bostick.” NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Edited Oral History Transcript. 23 February 2000. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/BostickJC/BostickJC_2-23-00.htm. Accessed May 24, 2014.

- Glynn S. Lunney. Interviewed by Roy Neal. NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Edited Oral History Transcript. Houston, Texas – 9 March 1998. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/LunneyGS/LunneyGS_3-9-98.htm. Accessed May 31, 2014.

- “…it was in some respects rewarding, because if you did the right thing, you felt good about it. Or if you did the wrong thing, you'd say, ‘Well, at least I learned something. I did what I thought was the right thing, but it turned out maybe we need to look at that a little bit more.’ So the simulations were very valuable. In fact, I've always thought that the simulation people were kind of unsung heroes in the manned spaceflight program, because they didn't get any credit for anything. They weren't in the limelight. Once the mission started, they kind of went away and started working on the next mission. But they knew their jobs, they knew the jobs of the people in the control center as well as the people who sat at the consoles, and they had to.” Interview with Jerry C. Bostick by Carol Butler, NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Edited Oral History Transcript. 23 February 2000. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/BostickJC/BostickJC_2-23-00.htm Accessed May 24, 2014.

- Jerry Bostick, personal email to the author. May 13, 2014.

- Sy Liebergot with David M. Hartland Apollo EECOM: Journey of a Lifetime. Burlington, Ontario, Canada: Apogee Books: 2003. p. 90.

- Sy Liebergot with David M. Hartland Apollo EECOM: Journey of a Lifetime. Burlington, Ontario, Canada: Apogee Books: 2003. p. 90

- Personal email to the author from Gene Kranz, July 5, 2014.