Deferred decisionby Jeff Foust

|

| “One of the main things I’m looking for is the extensibility to a Martian mission,” Lightfoot said of the two ARM options. “I want to build as little ‘one-offs’ as we can.” |

That was, at least, the plan. But when Lightfoot held a teleconference with the media on December 17, he offered a surprise. The meeting had taken place, and the presentations given, he said. But, he added, he wasn’t quite ready to make a decision between the two. The two options, he said, are so closely matched that he needs more information to make a decision between the two, a decision that won’t happen now until some time in January.

Bag or grab

The heart of the debate has been how to move a near Earth asteroid into orbit around the Moon. With a human mission to a near Earth asteroid in its “native” orbit ruled out for the foreseeable future because of the long durations of such missions, NASA planned to instead redirect an asteroid into a high altitude, stable orbit around the Moon that could be visited by astronauts on missions lasting only a few weeks.

The original concept for ARM was based on a study by Caltech’s Keck Institute for Space Studies in 2012. A robotic spacecraft would travel to a small near Earth asteroid, up to about 10 meters across, and use its ion thrusters to adjust the asteroid’s orbit towards cislunar space. In versions of this overall concept, the robotic spacecraft would envelop the entire asteroid in essentially a giant bag.

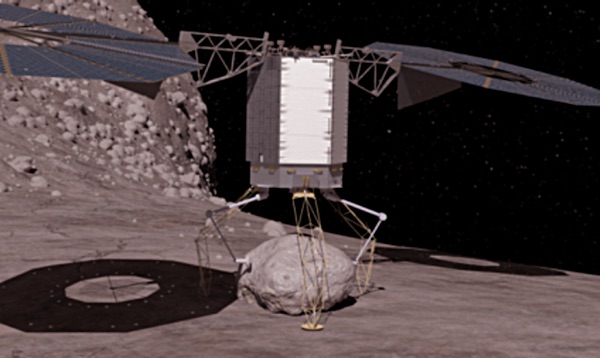

However, NASA has also been studying an alternative technique in parallel with the original design. In this approach, a robotic spacecraft would travel to a larger asteroid, perhaps hundreds of meters in diameter. Instead of trying to move the entire asteroid, though, the spacecraft would approach the asteroid and grab a boulder a few meters across from its surface and redirect it into lunar orbit.

The two approaches—redirect an entire asteroid or take a boulder off a larger asteroid—are known officially by NASA as simply Options A and B, respectively. Many, though, refer to the options more descriptively as “bag” and “grab.”

Two NASA teams had been working independently for several months to study each option. The goal was to have those reviews done by December, at which time NASA would select one of the options as the baseline for ARM. The timing of that would give NASA time to incorporate the specific details of the winning option into a mission concept review in February, where details about the cost and schedule of the mission would be confirmed.

In an interview early this month at the Kennedy Space Center, Lightfoot discussed some of the factors he planned to consider at the December 16 meeting about the two ARM options. “We do have a matrix” of factors that NASA will use to judge the two options, he said.

One of those factors was how well each option demonstrated technology that could be repurposed for later exploration missions, including journeys to Mars. “One of the main things I’m looking for is the extensibility to a Martian mission,” Lightfoot said. “I want to build as little ‘one-offs’ as we can.”

That fits into NASA’s broader exploration strategy, which treats cislunar space, and near Earth asteroids, as a “proving ground” to develop technologies before going to Mars. “We really think that if we can bring this asteroid back into this area around the Moon, we’ll have plenty of things that we can prove, all of which can be extensible to a mission to Mars as some point.”

NASA also planned to take into account the technical and budgetary risks associated with each option. Another factor was the potential for commercial partnerships. That would include, he said, “commercial entities coming in either to help us do this, or even take advantage of it once we’ve done it.”

| “Honestly, I expected to make a decision today,” Lightfoot said. “We really got to the point where I needed to get some more clarification on some areas.” |

Lightfoot said he would evaluate this with the support of what he dubbed the “Three G’s”: associate administrators Michael Gazarik, William Gerstenmaier, and John Grunsfeld, representing the agency’s space technology, human exploration and operations, and science mission directorates, respectively. “Those guys are my advisors as we move forward,” he said. That also reflected the fact that ARM is, for now, a program spread across those three directorates.

However, the decision on which option to pursue was his alone. “I’m actually the decision guy for this one,” he said, adding he would consult with NASA administrator Charles Bolden before announcing the decision.

“Just so close”

At the time of that early December interview at KSC, Lightfoot said an announcement of the decision could come the same day as the meeting—December 16—or a day later, depending on when he made the decision and consulted with Bolden. So, there was little surprise when NASA announced on the morning of the 17th that it would hold a media teleconference later that day to “discuss and answer questions on the selection of an Asteroid Redirect Mission concept.”

The assumption, of course, was that NASA had made a selection. But several minutes into the call, Lightfoot threw the media a curve. “Honestly, I expected to make a decision today. We really got to the point where I needed to get some more clarification on some areas,” he said.

Instead of making a decision on Option A versus Option B, Lightfoot said he instructed the teams to go back and do some follow-up analysis over the next two to three weeks. Lightfoot now expects to make a decision between the two options some time in January.

Lightfoot said that the reviews indicated that the two options were simply too closely matched for him to make a decision now. “I had one particular independent review team, they did an assessment of the figures of merit, and it came out that three were good in one way, three were good in another way, and two were a dead tie,” he said. “So I said, ‘Thanks a lot. You really helped me there.’”

“It was just close,” he said. “We needed more information in a couple of areas to make sure we were making the right call here.”

While the jury may still be out regarding the option ARM will pursue, Lightfoot suggested, if not a preference for Option B, then a focus on some of the issues surrounding it. That option, he indicated, had an advantage over Option A in terms of technology. “It demonstrates a lot more of the technologies that we need,” he said.

That additional technology, though, comes with complexity: in Option B, a spacecraft would have to land on—or come within a few meters of the surface of—an asteroid, grapple a boulder, and pull it away. “What I’m asking, for the most part, is how comfortable we are with the complexity of the mission,” he said. “There were questions around that complexity.”

“It’s the complexity associated with taking the boulder off the asteroid versus the technology development you get by doing that that is extensible” to future exploration missions, he said, that was the key issue in the debate about Option B.

Cost was also a factor. While he didn’t disclose the estimated costs of each mission, he did state that Option B cost about $100 million more than Option A in the estimates developed by the teams. “That’s the discussion we have to have: if I was to go one way or another, what do I get for that $100 million?” he said.

| NASA and the Obama Administration, Binzel wrote, “should abandon the ARM mission concept and make an asteroid survey its top priority to provide a basis for future crewed missions.” |

Both options, though, cost less than the goal Lightfoot had previously set of $1.25 billion, or about half the estimate from the Keck study. (That cost does not include the launch of the robotic mission itself; Lightfoot said NASA was considering the Delta IV Heavy, Falcon Heavy, and Space Launch System.) NASA will perform an independent cost assessment of the selected ARM option in advance of the mission concept review, scheduled for late February.

The date of that review could slip slightly, he said, because of the delay in selecting an option, but wouldn’t affect ARM’s overall schedule. “Taking two or three weeks now is not going to change the overall schedule,” he said.

“A multibillion-dollar stunt”

The delay in the decision about ARM comes as both scientists and members of Congress have continued to criticize the overall mission concept (see “Feeling strongARMed”, The Space Review, August 4, 2014). As the decision approached, that criticism showed few signs of abating.

In a commentary published in the journal Nature in late October, MIT planetary sciences professor Richard Binzel reiterated previous criticism of ARM. The mission, he wrote, “is a multibillion-dollar stunt” that requires technologies to move an asteroid or grab a boulder off of it that will not be “useful for getting humans to Mars.”

Binzel advocated instead for a human mission to a near Earth asteroid in a native orbit as a more logical stepping-stone to human missions to Mars. Enhanced asteroid surveys, he argued, could detect potentially thousands of additional objects that could be in reach of such a mission. NASA and the Obama Administration, he wrote, “should abandon the ARM mission concept and make an asteroid survey its top priority to provide a basis for future crewed missions.”

Congressional skepticism of ARM lingers as well. “I don’t like the infighting over what the destination may or may not be,” said Rep. James Bridenstine (R-OK), a member of the House Science Committee’s space subcommittee, in a December 17 interview. “I think we need to figure out what our destination is, we need to all resolve to make that our objective, and we need to move forward given the constraints of the budget. NASA needs to focus like a laser on accomplishing that objective.”

Bridenstine said he was “agnostic” about what that destination should be, but indicated he had issues with ARM, given concerns about its development of “dead end” technologies that may have limited future use, and a potential lack of interest from international partners. “An asteroid redirect mission, from a lot of the testimony I’ve heard, is not the right answer.”

| “An asteroid redirect mission, from a lot of the testimony I’ve heard, is not the right answer,” Rep. Bridenstine said. |

However, in the fiscal year (FY) 2015 omnibus spending bill that Congress passed earlier this month (see “Of budgets past and future”, The Space Review, December 15, 2014), Congress included no restrictions on NASA’s continued development of ARM. “The omnibus that was just passed had all the things we needed for FY15, so we’re going to keep pressing” with ARM-related activities in all three mission directorates, Lightfoot said.

In the KSC interview earlier this month, Lightfoot indicated that at least some members of Congress were more supportive of the ARM concept now. “We’ve briefed them several times about the mission,” he said of members of Congress. “We continue to get the budget to allow us to go do this.”

However, both skeptics and supporters alike will have to wait a little longer to see exactly what form ARM will take. “I was so impressed with our teams and what they did,” Lightfoot said of the teams who studied the ARM options. “It was exciting to see the teams so jazzed about what they were working on, too, which makes it even harder.”