Encouraging private investment in space: does the current space law regime have to be changed? (part 1)by Jonathan Babcock

|

| In any industry, legal uncertainty hinders private investment. Accordingly, a cloudy legal regime in space has hampered the ability of private individuals and firms to raise the capital necessary to fund space activities. |

This article will analyze the problems facing private actors in space, and will offer a practical solution to overcome them. First, it will describe the obstacles that private actors face in undertaking commercial space ventures. It will then analyze the current legal regime governing space activities, such as the 1967 Outer Space Treaty and 1979 Moon Treaty. Finally, the article will examine various proposals for making international space law more amenable to private investment. This comparison will show that we don’t need a wholesale replacement of the Outer Space Treaty with a new legal regime. Instead, a solution realizing limited property rights within the existing legal structure provided by the Outer Space Treaty best serves to encourage future private investment while still upholding the necessary prohibition on national claims of sovereignty in space.

Private commercial actors in space

Regardless of the field, private actors are chiefly motivated by profits. Exploration and innovation are not done solely in an altruistic manner to benefit society (although that is sometimes the case), but rather as a means to secure profits.1 This is true of private commercial actors in space, where both individuals and companies are already undertaking, or plan to undertake in the near future, commercial ventures that have come to be labeled under the umbrella category of private space exploration.2 This refers to a diverse set of activities undertaken by private actors in space such as space mining, launch services (highlighted by Elon Musk’s space transportation company, SpaceX), and space entertainment (mostly in space tourism such as Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic).3 Branson and Musk are not alone in viewing space as the next untapped market to be exploited for massive profits. Other individuals such as Paul Allen, Jeff Bezos, James Cameron, Robert Bigelow, and John Carmack are engaged in investing in space, albeit in varying degrees.4 These “astropreneurs,” as they are sometimes called, share common traits that cause them to be interested in investing in space.5 After all, commercial investments in space are not the simplest way to earn a profit. So what is it that makes these individuals interested in space on a personal level? Outside of having incredible personal wealth that allows them the luxury of expendable income, these individuals share a fascination with space and possess the know-how to navigate the complex world of high-tech industries.6 They are motivated by these personal interests and skills to turn their commercial investments in space into profitable ventures.

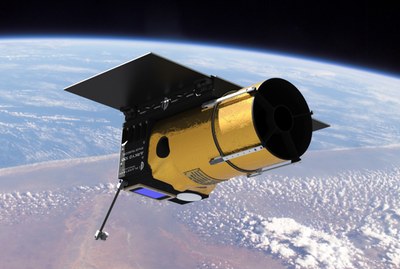

In addition to these individuals, companies such as Planetary Resources, Deep Space Industries, and Moon Express and have shown interest in undertaking ambitious commercial projects in space in the upcoming decades.7 These companies highlight the potential of space to not only provide massive profits but to also hold the keys to solving societal problems here on Earth, such as energy and natural resources.8 However, these interests are currently primarily in space mining, an industry that has yet to become technologically feasible in a sense that would make it economically viable, but potentially could offer immense profits. US companies such as Deep Space Industries and Planetary Resources have announced plans to begin mining asteroids by 2020 to 2025.9

What is it that causes such optimism in space mining? Namely, these companies argue that space is teeming with valuable resources.10 In near Earth asteroids alone (which are the most feasible in terms of near-future technological advances), there may potentially be vast amounts of iron, nickel, cobalt, magnesium, and gold, along with reserves of water and its constituents, hydrogen, and oxygen.11 Platinum, another valuable metal on Earth, is also believed to be available to mine in space albeit further in the future.12 If successful, the entire cost of establishing the mining operation could be paid off with the delivery of only a couple tons of these respective materials back to Earth.13 Yet, despite the potential for vast profits, private actors have been more reluctant than one would imagine in undertaking such ventures in space.

Several reasons exist for their hesitation. For one, technology is not yet at the point where these ventures are clearly feasible. Given the cost of reaching the desired destinations in space, coupled with the limitations of modern technology, it is premature for these companies and individuals to believe they will see profits from space mining in the near future.14 However, a more philosophical problem exists that many private actors identify as one of the main impediments to further private commercialization of space. This problem involves the scope of private property rights in space: whether they exist at all, and if they do, what is their applicability to resource extraction.15

Space law, derived mainly from the Outer Space Treaty and the Moon Treaty (the latter’s principles carry weight despite having a few signatory states), prohibits national appropriation in space and states that space is a domain for the “common heritage of mankind.” The meaning of these documents, particularly pertaining to their applicability to private actors in space, is ambiguous and contentious, as will be shown in the following section. In any industry, legal uncertainty hinders private investment. Accordingly, a cloudy legal regime in space has hampered the ability of private individuals and firms to raise the capital necessary to fund space activities.16 Moreover, private actors hold that the absence of a legal regime clearly defining the scope of property rights in space deprives them of the assurance that they will reap benefits that will outweigh the capital they invested.17 They argue that the main impediment to further private action in space is that the current legal regime jeopardizes the ability of private actors to make a profit in space.

This is a discouraging climate for private innovation, and will surely discourage future investment in space. The legal regime governing space must be clarified, added to, altered, or changed entirely to encourage private investment in space by allowing actors to realize financial rewards.18 The question then becomes how to accomplish this. In order to better understand the inadequacies of the current legal regime, it is necessary to analyze what exactly the Outer Space Treaty and Moon Treaty state, and how they dictate the climate in which private actors are operating in space.

The legal regime in space

Modern space law emerged mostly in the 1960s and 1970s, in the midst of the Cold War, and has seen little revision since. This backdrop made sure that the legal regime addressed concerns over claims to national sovereignty in space by prohibiting national appropriation, and aimed at preventing tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union being brought to space.19 There are four principal reasons why both the US and Soviet Union sought to create a legal regime prohibiting sovereign claims and encompassing Cold War concerns:

- they wanted to prevent an expansion of conflict to outer space;

- they sought to preserve the doctrine of free access to space;

- they knew that delineating boundaries in space would cause tension, and;

- they wanted to enhance their prestige vis-à-vis Third World states who would be pleased with a prohibition on sovereign claims in space.20

These were valid concerns at the time, and were codified in five principal treaties that, together, account for the current international space law regime. A concern offered by many private actors in space, however, is that the doctrines in these treaties, influenced by the Cold War, are outdated and need to be altered to better reflect the current climate of increasing private commercial interest in space.

| There is little doubt that Article II of the Outer Space Treaty is of critical legal significance in terms of governing activities in outer space, but there has been debate over what exactly it means. |

The most important of these five treaties is the 1967 Outer Space Treaty. Four other international treaties from the Cold War era of the 1960s and 1970s complement the Outer Space Treaty: the Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts, and the Return on Objects Landed in Outer Space (“Rescue Agreement”); the Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects (“Liability Convention”); the Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space (“Registration Convention”); and the Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (“Moon Agreement”).21 For the purposes of this essay, the Outer Space Treaty and the Moon Agreement are of paramount importance. Together, these two treaties comprise the foundation of international space law, and are sometimes called the “Magna Carta of space.”22 The other three treaties are not entirely relevant to the present discussion. The cores of both the Outer Space and Moon Treaties will now be explained in turn.

The Outer Space Treaty, which forms the basis of law governing activities in outer space, was signed and ratified in 1967. An important element of the treaty is the fact that it is a statement of principles governing the desirable actions of parties in space, rather than rules clearly delineating substantive law.23 Although the language is often vague by legal standards (as the debate over the meaning of Article II will show), the treaty expects to set a pattern for behavior instead of a list of regulations.24 Essentially what the Outer Space Treaty accomplished was to take previously agreed upon United Nations principles on space activities and give them a legally binding form. Therefore, the Outer Space Treaty is sometimes referred to as the first “Space Charter.”25

Permeating the entire document is the notion that space is for the “common interest of mankind.”26 This was done in an attempt to address both the Cold War concerns of sovereign claims in space, and to ease the worries of developing states that space activities would only be done by wealthy, developed states at the expense of poorer ones. Article I of the treaty notes as much by stating that activities in outer space “shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development, and shall be the province of all mankind.”27 Given this notion of free access to space for all nations, the prohibition on national appropriation in space under Article II is not surprising. Article II states, “Outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.”28 There is little doubt that Article II is of critical legal significance in terms of governing activities in outer space, but there has been debate over what exactly it means.

| It is misguided to use the broad interpretation and state that the Outer Space Treaty prohibits all types of appropriation under Article II. |

Most of the tension has centered on differing interpretations of “national appropriation.” Some lawyers interpret the article in a narrow sense, using a text-based approach. In this sense, Article II only explicitly prohibits “national” appropriation.29 Others argue that Article II should be interpreted more broadly to prohibit all types of appropriation, both national and private.30 Private actors who argue that they have no legal grounds with which to claim property in space are articulating the broader interpretation of Article II. They argue that this prohibition on all appropriation hinders their ability to reap financial rewards from exploits in space.

However, when looked at more closely and in conjunction with the Moon Agreement, it will be shown that this broad interpretation is incorrect. The current legal regime in space does indeed allow for limited claims to property rights in space, drawing on Article XIII of the Outer Space Treaty. Therefore, there is a way in which the interests of private commercial actors in space could be safeguarded to encourage future investment within the existing legal regime. After all, terminology is not the deciding factor. Investors do not care if they enjoy full property rights or real limited property rights. They care about the bottom line: will a legal provision help them gain profits? If the answer is yes, then such a provision would solve the current problem of ambiguity in the existing legal regime and encourage increased private investment in space in the future.

In order to fully address the justification for using the strict interpretation of Article II rather than the broader one, it is necessary to understand how the Moon Agreement works in conjunction with the Outer Space Treaty. The Moon Agreement for the most part echoes the sentiments established in the Outer Space Treaty. It is more extreme in some respects, however. At the time it was drafted, it sought to address the status of property rights in space left open by the Outer Space Treaty.31 For example, as the Outer Space Treaty recognized a “common interest” in space shared by all countries, the Moon Agreement went further by asserting that space is the “common heritage of mankind.”32 While the idea of space as a “common interest” certainly existed in the Outer Space Treaty and in previous UN discussions on space activities, the notion of space being “the common heritage of mankind,” a further step in precluding any type of ownership in space, first appeared in the Moon Agreement.33

Drawing on this underlying idea, the Moon Agreement then states its most novel point in Article XI: that “neither the surface nor the subsurface of the Moon… shall become property of any state, international inter-governmental or non-governmental organization, national organization or non-governmental entity or natural person.”34 References to the “Moon” in the Moon Agreement are understood to refer to all celestial bodies.35 This non-appropriation clause is more inclusive than Article II in the Outer Space Treaty, and its language further expanding the explicit prohibition on property rights in space was very contentious at the time the treaty opened for signature in 1979, and remains to this day.36

The contentious nature of the contents of the Moon Agreement has, for all intents and purposes, limited its impact on international space law because it has very few signatory states. It is essentially a failed piece of international law because as of August 2014, only 16 states had signed it.37 Moreover, none of the major spacefaring nations has become a party to the treaty.38 The main point of contention precluding these states from acceding to the Moon Agreement is that it is too extreme in limiting the scope of commercial actions allowed in space, both national and private. For example, US private space industry viewed Article XI as essentially an all-encompassing moratorium on commercial space activities (much more so than the Outer Space Treaty, to which they also have great concerns.)39

Despite not having many parties to the treaty, the principles within the Moon Agreement carry weight when states think about actions in space. Therefore, taken together, Article II of the Outer Space Treaty, and, to a lesser extent, Article XI of the Moon Agreement, constitute the elements of the current space law regime that private commercial actors in space believe are hostile to their investments. Upon closer examination, however, this accusation does not hold up. The current legal regime in space, dominated by the two preceding agreements, does indeed allow for a limited form of property rights in space, when one takes a more nuanced look at the contents of these treaties.

| While the common rhetoric is that the current space law regime outlaws appropriation in space and thus discourages investment, this narrative does not paint a true picture. The two treaties simply outlaw unilateral appropriation. |

It is misguided to use the broad interpretation and state that the Outer Space Treaty prohibits all types of appropriation under Article II. Part of the prohibition on national appropriation in Article II is based on sovereign claims made by states in space. So at first glance, it would appear that current space law prohibits all sovereign claims in space. But this is not the entire picture. In fact, the Outer Space Treaty allows, and in some cases requires, that states have control over space facilities while not claiming them as part of their country.40 The most prominent example of such a provision is Article VIII, which requires parties to “retain jurisdiction and control over… space objects on their registry… and over any personnel thereof, while in outer space or on a celestial body.”41 This amounts to “quasi-territorial” jurisdiction being conferred by the Outer Space Treaty to state actors in space based on functional sovereignty rather than territorial sovereignty. This is different from sovereignty in the full sense of the word (absolute and based on territorial claims), which is still outlawed under Article II, but allows the state to have “ownership” of the space facility in a legal sense for a limited functional purpose. This jurisdiction applies to the space facility, a reasonable area around the facility, and all of the personnel in or near the facility irrespective of nationality.42 Article VIII jurisdiction permits the controlling state to subject any personnel in the facility to its national laws as long as they do not clash with international obligations. Thus, Article VIII allows for a limited version of property rights in space, in which a state can use a facility for its own purposes without having to make sovereign claims on it, providing evidence that Article II of the Outer Space Treaty is not a blanket prohibition on all forms of appropriation in space.

Moreover, two other less significant points give credence to the idea that no complete prohibition on private appropriation in space exists. First, Article VI of the Outer Space Treaty leaves open the possibility of private and “national” activities in space, but requires that they be supervised by a state that is responsible for their actions.43 So it seems as if private actors can undertake operations in space and appropriate for all intents and purposes so long as a state takes responsibility for their actions.

Second, the very existence of the Moon Agreement leads one to question whether Article II prohibits all appropriation. If the Outer Space Treaty outlawed all types of appropriation in space under a blanket Article II prohibition, would it be necessary for a subsequent treaty to outlaw appropriation of the Moon and celestial bodies?44 The answer to that question seems to clearly be no. Taken together, these provisions show that the Outer Space Treaty does prohibit national appropriation in space, but leaves open the possibility of private appropriation. There is no denying that this possibility is ambiguous, however, and this ambiguity will serve as a reason for why the current system should be clarified or altered, but not replaced, to further encourage private investment in space.

Like the Outer Space Treaty, the Moon Agreement also contains provisions under which appropriation in space is allowed, thus proving that industry fears of a legal regime that outlaws all appropriation in space is misguided. As stated before, the Moon Agreement holds that space and space resources are the “common heritage of mankind.” But if that is true, could not “mankind” decide to appropriate space for its own benefit? What would constitute “mankind” in that scenario? One could envision a system in which an international organization works by international consensus to authorize appropriation in space of the Moon or other celestial bodies.45 Therefore, it can be argued that the Moon Agreement establishes a prohibition on appropriation of the Moon and celestial bodies, but leaves open the opportunity to work around this prohibition based on an authorizing regime governed by international consensus. In other words, the Moon Agreement permits the exploitation of celestial bodies provided that an international regime is established to govern the process.46 So while the common rhetoric is that the current space law regime outlaws appropriation in space and thus discourages investment, this narrative does not paint a true picture. The two treaties simply outlaw unilateral appropriation.47 Therefore, these treaties allow for provisions to be taken to clarify the existing regime to make it more attractive to investors.

Endnotes

- Lawrence Risley, “ Examination of the Need to Amend Space Law to Protect the Private Explorer in Outer Space,” Western State University Law Review (1999), p. 47.

- Ozgur Gortuna, Fundamentals of Space Business and Economics, (Springer: 2013), p. 56.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 57.

- Ibid.

- Laura, Delgado-Lopez, “Beyond the Moon Agreement: Norms of Responsible Behavior for Private Sector Activities on the Moon and Celestial Bodies,” Space Policy (2014), p. 2.

- Zach Meyer, “Private Commercialization of Space in an International Regime: A Proposal for a Space District,” Northwestern Journal of International Law and Business (Winter 2010), p. 6.

- Fabio Tronchetti, “Private Property Rights on Asteroid Resources: Assessing the Legality of the Asteroids Act,” Space Policy (2014) p. 2.

- Rand Simberg, “Property Rights in Space,” The New Atlantis (Fall 2012), p. 1.

- Tronchetti, “Private Property Rights on Asteroid Resources,” p. 1.

- Simberg, “Property Rights in Space,” p.1

- Eva-Jane Lark and Dale S. Boucher, “Space Mining: ISRU as a Driver for a New Economic Space Exploration Model,” Presented at Global Space Exploration Conference 2012, p. 1.

- Henry R. Hertzfeld and Frans von der Dunk, “Bringing Space Law into the Commercial World: Property Rights Without Sovereignty,” Chicago Journal of International Law (Summer 2005) p. 86.

- Ibid.

- Simberg, “Property Rights in Space,” p.1

- Hertzfeld and von der Dunk, “Bringing Space into the Commercial World,” p. 81.

- Risley, “Examination of the Need to Amend Space Law,” p. 48.

- Ibid., p. 57.

- Wayne N. White, “Implications of a Proposal for Real Property Rights in Outer Space,” Proceedings, 42nd Colloquium on the Law of Outer Space (2000), p. 366.

- Meyer, “Private Commercialization of Space in an International Regime,” p. 248.

- Ashley A. Hutcheson, “Dollars and Sense: Why the International Space Station is a Better Investment than Deep Space Exploration for NASA in a Post-Columbia World,” Journal of Law, Technology, and Policy (2004) p. 3.

- Jeffrey Prevost, “Law of Outer Space Summarized,” Cleveland State Law Review Vol. 19 (1970) p. 606.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Meyer, “Private Commercialization of Space in an International Regime,” p. 250.

- Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, Jan. 27, 1967, U.N.T.S. 205 [hereinafter Outer Space Treaty], Art. I.

- Ibid., Art. II.

- Wayne N. White, “Real Property Rights in Outer Space,” Proceedings 40th Colloquium on the Law of Outer Space (1998) p. 370.

- Ibid.

- Glenn Harlan Reynolds, “The Moon Treaty: Prospects for the Future,” Space Policy (1995) p. 3.

- Meyer, “Private Commercialization of Space in an International Regime,” p. 251.

- Antonella Bini, “The Moon Agreement: Its Effectiveness in the 21st Century,” ESPI Perspectives (2008) p. 4.

- Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, Dec. 5, 1979, G.A. Res. 34 68, (1979) [hereinafter Moon Treaty], Art. XI.

- White, “Real Property Rights in Outer Space,” p. 370.

- Delgado-Lopez, “Beyond the Moon Agreement,” p. 2.

- Simberg, “Property Rights in Space,” p.2.

- Meyer, “Private Commercialization of Space in an International Regime,” p. 250.

- Delgado-Lopez, “Beyond the Moon Agreement,” p. 2.

- Risley, “Examination of the Need to Amend Space Law,” p. 53.

- White, “Real Property Rights in Outer Space,” p. 370.

- White, “Implications of a Proposal for Real Property Rights in Outer Space,” p. 366.

- Simberg, “Property Rights in Space,” p.2.

- Ibid., p. 3.

- Meyer, “Private Commercialization of Space in an International Regime,” p. 251.

- Ibid., p. 255.

- Ibid., p. 253.