Review: Starmusby Jeff Foust

|

| The reader is left wondering why a book celebrating “50 years of man in space,” as its subtitle states, is also featuring speakers on topics such as astrobiology, dark matter, and the origins of the universe. |

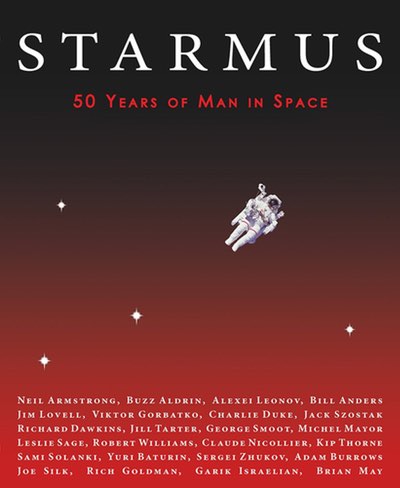

Those presentations have been, belatedly, compiled into a book, Starmus: 50 Years of Man in Space, first released last fall at the second Starmus festival and more recently published in the United States. The book provides richly illustrated versions of the speakers’ talks (or, in one case, a transcript of an on-stage interview) on either their spaceflight experiences or their scientific areas of expertise. Given the A-list of participants, it should be a compelling book.

And yet, Starmus, at least in print form, falls flat. In most cases the speakers cover familiar ground: space travelers talk about their missions, scientists discuss their research. Pictures of the event included in the book show those speakers had an opportunity to interact and talk, but those discussions, whether formal or informal parts of the conference, aren’t otherwise captured in the book. What’s left for the book are essays that have little connection with one another.

The reader is also left wondering why a book celebrating “50 years of man in space,” as its subtitle states, is also featuring speakers on topics such as astrobiology, dark matter, and the origins of the universe. The connection between astronomy and astronautics is a weak one, and one wonders why they’re brought together here. One speaker, Claude Nicollier, did offer a connection between the two, as the Swiss astronaut flew on two servicing missions for the Hubble Space Telescope, but his essay is shunted to near the end of the book. Starmus, with its focus on human spaceflight and the distant universe, also oddly overlooks the leaps and bounds in planetary exploration in the last half-century, an area where the connections to human spaceflight are at least somewhat stronger.

There are a few places where speakers venture beyond familiar ground. Armstrong does try to connect spaceflight with astronomy in his essay. The Earth, he notes, may be our home, but it won’t always be hospitable. “The universe around us is both our challenge and perhaps our destiny,” he writes.

| “Based on our record here on Earth, we are not yet qualified to populate and govern a larger segment of the universe,” Armstrong wrote. “Yet there is a great reason for hope. And we have no other choice.” |

That essay, contributed for the book several months after the festival, is something of a counterpoint to one by Brian May, who received his PhD in astronomy in 2008 after interrupting his studies more than 35 years earlier to devote himself to the band he was a member of: Queen. May’s essay highlights all the flaws in humanity and wonders if we’re ready as a civilization to go into space. (That arguments includes, oddly, a comparison of his failure to win a £10,000 grant for zodiacal dust studies with the several hundred million dollars NASA spent on the Deep Impact spacecraft mission: “please don’t tell me that military considerations have nothing to do with the decision making process.” Well…)

May writes that he wants to “find a way to propagate just the decent, noble parts of our civilization” into space. That’s not too different from Armstrong, who wrote, “Based on our record here on Earth, we are not yet qualified to populate and govern a larger segment of the universe.” Armstrong, though, sounded more optimistic: “Yet there is a great reason for hope. And we have no other choice.”

That subtle point-counterpoint shows what Starmus could be: a true exchange of, and debate about, ideas regarding astronomy, spaceflight, and humanity’s place in the universe. Instead, this book is a just record of what was presented at the conference, illustrating the dangers of compressing a dynamic festival into a static text.