Phobos indeedby Louis Friedman

|

| Going to Martian orbit before landing is a good idea—and an obvious one. That is all logical, but treating that as an alternative to ARM is not. |

Russian advocacy is also well known, as it was the genesis of their efforts to develop a robotic mission to sample Phobos. The Russians were initially motivated in part by Josef Shklovsky’s suggestion that Phobos might be an artificial satellite of an alien civilization. He thought that its density would indicate it was hollow. Unfortunately, science conspired against Phobos mysticism: it isn’t hollow and, while carbonaceous, its resources are probably limited to simple dirt (which might nonetheless be useful for radiation protection.) Spacecraft measurements indicate there is likely little if any water (or ice) in its regolith.

Nonetheless, Phobos and Deimos are natural targets on which to observe Mars and perhaps even set up a communications base for eventual surface exploration. Going to Martian orbit before landing is a good idea—and an obvious one. No one in the space business thinks a human mission to the surface wouldn’t be preceded by human missions to Martian orbit, although interplanetary round-trip missions with a flyby might turn out to be more economical and just as advantageous as a precursor. This is what was done in the Apollo program for the Moon. The satellites are not an alternative goal for Martian exploration, but they can be a precursor. Michael Griffin co-led a Planetary Society study in 2004 (with Astronaut Owen Garriott) in which he made this same point—and even recommended that the Mars orbiter or flyby should be conducted before another lunar landing, due to the expense of developing the lander. He obviously changed his mind after becoming NASA administrator.

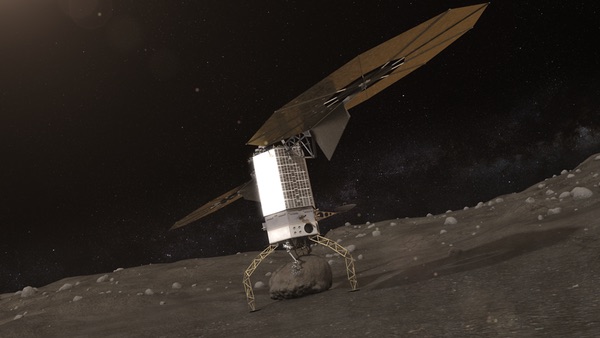

People now have renewed interest in the Martian satellites, such as in the JPL study reported at a workshop organized by The Planetary Society and in the recommendation of the NASA Advisory Council (NAC) at its meeting earlier this month seeking an alternative to the Asteroid Redirect Mission (ARM). The JPL study included the same recommendation of a Mars flyby or orbiter before a lunar or Mars landing, as was in the Griffin-Garriott report. That is all logical, but treating that as an alternative to ARM is not. Any capability to do a human mission to the vicinity of Mars is a decade later and tens of billions dollars more expensive than a human mission to an asteroid moved to lunar orbit. If NASA followed the NAC recommendation, it would be another decade without human exploration of anything and a rocket that would have been built to go nowhere. And by nowhere, I mean to no other destination except empty space.

It is hard to understand the rationale for the NAC recommendation, or the reasoning by its chairman, Steve Squyres, who says that the robotic SEP development mission should carry out its flight without a payload or any purpose other than just running its engines. It would not be an endorsed as a science mission—Phobos and Deimos flybys are not part of any decadal or other science advisory recommendation. Apparently the NAC likes the “getting ready for Mars” aspect of ARM but not the actual accomplishment of providing a science target for humans in the near term. They, and the science critics of ARM, are willing to defer human exploration and operations on a celestial body for a decade, and do no human-crewed science, in order to have a more pure program not relying on the engineering innovation of moving an asteroid. Ironically, this time it is not NASA that is afraid to innovate, but instead its advisors.

| NASA embraced ARM to deal with all these jobs, and the resulting architecture that created a human path to Mars should now be embraced by the space community. The alternative will be to repeat the 1970s decision about architecture: let NASA build vehicles but don’t let them go anywhere. |

We space enthusiasts would like to move more quickly and directly into the solar system with humans. Unfortunately, it requires rockets and crew habitability support we do not have and cannot afford for at least another five to ten years after the International Space Station. To stand down with human achievement while we wait with uncertainty is a strange recommendation, motivated either by wishing for more money or by ideas of pure logic without respect to constraints or real world conditions. The suggestion to avoid the redirected asteroid by building a habitat destination (that is, another space station) in lunar orbit is equally impractical, requiring billions of dollars not in the current plan, and delaying the human space venture even more.

Wishing for more money when all evidence is to the contrary is not a good strategy. NASA has difficult jobs: they have to want to send humans to Mars or to a lunar base with money no one is willing to appropriate; they have to inspire and lead the world with human achievements beyond the Moon with systems that can barely get there; and they have to respond to all kinds of self-interest communities with their favorite targets, experiments, and even ideologies while still performing the real instead of the imaginary. They have to be safe and take risk. NASA embraced ARM to deal with all these jobs, and the resulting architecture that created a human path to Mars should now be embraced by the space community. The alternative will be to repeat the 1970s decision about architecture: let NASA build vehicles but don’t let them go anywhere.