Review: Elon Muskby Jeff Foust

|

| “Hey, guys,” Musk said after efforts to buy a Russian launch for a Mars mission failed in 2002, “I think we can build this rocket ourselves.” |

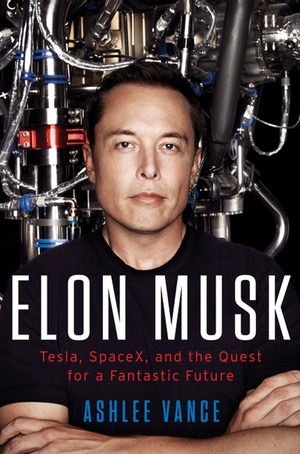

Elon Musk, the new book by Bloomberg Businessweek reporter Ashlee Vance hitting shelves this week, is the most thorough effort to date to describe someone who has become not just a central figure in the space industry, but in business in general thanks to efforts at Tesla and SolarCity. Vance interviewed hundreds of people—family members, current and former business associates and employees, and ultimately Musk himself—in writing this book. (Musk initially declined to cooperate with Vance, but ultimately relented and agreed to a series of interviews.) Vance left few, if any, stones unturned in his effort to learn about Musk.

Most readers of this publication will be interested in this book to learn about Musk’s work in building up SpaceX from nothing to a major space transportation company in a decade. About the first 100 pages, though, is about Musk’s family history, growing up in South Africa, and his early entrepreneurial efforts, first with an online business directory called Zip2, and then an online banking venture, X.com, that merged with, and later took the name of, PayPal. These make scant mention of any interest in space other than “childhood fantasies around rocket ships and space travel.”

Yet, it was the “call of space” that got Musk to move from Silicon Valley to Los Angeles in 2001, as he stepped away from X.com. “While Musk didn’t know exactly what he wanted to do in space, he realized that just by being in Los Angeles he would be surrounded by the world’s top aeronautics thinkers,” Vance wrote. He was initially interested in some kind of Mars mission: first in sending mice to Mars and back to see if they would survive the trip, and later landing a greenhouse on Mars. Those efforts bogged down because of the expense, particularly for the launch itself. (For more information about that effort as it was under development, listen to an interview Musk did with David Livingston of what is now known as The Space Show in October 2001.)

Musk initially tried to procure a launch from Russia, using repurposed ICBMs, but was effectively rebuffed by the Russians, who didn’t take him seriously despite his wealth. When a second meeting in Moscow ended badly in February 2002, Musk and his advisors, which included Mike Griffin, left town on a private jet. It was during the flight back when, as another advisor, Jim Cantrell, recalled, Musk turned to them and said, “Hey, guys, I think we can build this rocket ourselves.”

“This rocket” was the small launch vehicle that would become the Falcon 1, and “we” was the company that Musk would soon establish, Space Exploration Technologies, or SpaceX. The rise of SpaceX, and the challenges it faced along the way in developing its launch vehicles and its Dragon spacecraft, runs in parallel in the book with the development of Tesla, the electric car company also run by Musk.

To those who have followed SpaceX closely since its beginnings 12 years ago, that origin story—founding a rocket company after failing to buy a Russian launch—sounds familiar. And that familiarity rings throughout the book. There’s little in the book to revise the major outlines in the company’s story: developing Falcon 1, its initial launch failures followed by a successful launch in September 2008 when the company was running short on funds, and development of Falcon 9 and Dragon to pursue NASA commercial cargo and crew missions, among other customers.

| Five years ago Musk penned an email criticizing the “creeping tendency” for developing acronyms at the company. Its subject line was “Acronyms Seriously Suck.” |

What Vance’s book does, though, is help fill in those outlines with details and anecdotes that flesh out the story. For example, after the third Falcon 1 launch failure in August 2008, the company decided to ship the next Falcon 1 to Kwajalein by military transport plane, rather than by ship, to accelerate the schedule for the launch. During the flight, though, pressure differences between the plane’s cabin and the rocket caused parts of the rocket to buckle. “The thinking at the time was that it would take three months to repair the damage,” Vance writes. Instead, SpaceX completed the repairs at Kwajalein in two weeks, and successfully launched the rocket in late September.

While Musk is as famous, if not more so, in many circles for leading Tesla, Vance sees SpaceX as perhaps the purest expression of Musk’s vision. “Zip2, PayPal, Tesla, SolarCity—they are all expressions of Musk. SpaceX is Musk,” he writes. “Its foibles emanate directly from him, as do its successes.” Musk is intimately involved in seemingly all aspects the company. For example, five years ago he penned what is internally now considered a famous email criticizing the “creeping tendency” for developing acronyms at the company. That memo also revealed his sense of humor: its subject line was “Acronyms Seriously Suck.”

Musk has become famous for his brilliance, including his self-taught knowledge of aerospace, he’s also become infamous for micromanagement and what can seem to be harsh treatment of his employees and others. Some accuse him of a lack of empathy, such as when he unceremoniously let go of his longtime executive assistant. They wonder if even Musk is “somewhere on the autism spectrum” given a perceived inability to consider others’ emotions. Musk himself asked Vance, at the end of one of their interviews, “Do you think I’m insane?”

Vance doesn’t think so. He sees Musk as a driven man, someone “profoundly gifted” but also attempting “to soothe a type of existential depression that seems to gnaw at his every fiber.” Musk, to him, is a “man on a quest” with goals like making humanity a multiplanetary species. “He seems to feel for the human species as a whole without always wanting to consider the wants and needs of individuals,” Vance concludes.

That is the value of Vance’s book: a detailed portrait of a figure both loved and feared—sometimes by the same people at the same time. It’s largely a sympathetic one as well to Musk, who Vance sees as a “deeply emotional person” who can seem “aloof and hard.” Elon Musk may not have the level of detail about SpaceX’s development as some space fans would like, but compressing Musk’s life into less than 400 pages does impose its limitations. (One oversight, at least in the hardbound review copy provided by the publisher, is a lack of an index.) It does, though, offer a more detailed picture of the man who vision and drive made it all possible.