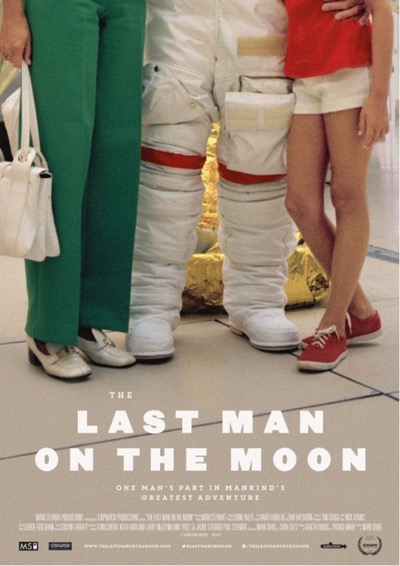

Humankind’s greatest adventure: A review of The Last Man on the Moonby Shane Hannon

|

| This film is not about Gene Cernan. Sure, we are taken on a journey, but the film is about what this journey meant and continues to mean. |

Whether he and his colleagues would admit it or not, Cernan and the other Apollo-era astronauts had the “Right Stuff.” They were steely-eyed missile men. Some of them even landed jets on aircraft carriers floating violently like a cork in the sea—at night. What we tend to forget though, and what this film reminds us of, is the human side of going to the Moon.

This film is not about Gene Cernan. It’s not the 95-minute résumé of a now 81-year-old retired naval aviator and NASA astronaut. Sure, we are taken on a journey, but the film is about what this journey meant and continues to mean. It is in some ways, in the words of the film’s director Mark Craig, “A call for Americans to remember what an incredible thing they once did and how, if a group of brilliant people put their minds together with a plan, anything is possible—if the desire is there.”

Right now the desire simply isn’t there: humankind has been confined to low Earth orbit (LEO) ever since Cernan climbed back up the ladder of his lunar module in December 1972 and returned to Earth with his two crewmates. That is the sad reality, and yet it is a fact that should not take away from the privilege of watching a film that so powerfully encapsulates the man behind the spacesuit, in a way that has simply never been done before. The film was recognized as the “Most surprising tearjerker” at its US premiere at the South By Southwest (SXSW) festival in Austin, Texas, in mid-March, and you really will need to fight back the tears in parts.

It is clear Cernan has some regrets about the lack of family time available to him throughout the 1960s and early ’70s, but that was the price of flying in space three times, twice to the Moon. One powerful moment arrives when Cernan’s ex-wife Barbara attests, “If you think going to the Moon is hard, you should try staying at home.” Cernan has been in the public spotlight ever since the Apollo days, and the intrigue has only continued to grow as he looks set to be the last human being of twelve to set foot on our desolate neighbor in space for some time to come. He is extremely well-versed in public speaking and has plenty of anecdotes and soundbites that he spews out in interviews and lectures, but producer Gareth Dodds acknowledges this film was about going deeper: “The challenge for us was getting beyond all of that to the emotional core, to the stuff no one has heard before.”

It could’ve been any astronaut’s life immortalized on the big screen for younger generations to be inspired by, but the fact is it wasn’t. And for that I am grateful, because the fervent passion in Cernan’s voice as he reminisces about his past is palpable throughout. Craig admits there were two main reasons why it was Cernan and not another astronaut featured in the film.

“There were some great astronauts who went to the Moon and who were incredibly gifted at flying those pioneering space machines, but not all of them were particularly charismatic or engaging characters that had the ability to communicate their experiences to the layman back home on Earth,” he said. “Gene is one of the people who can do that.”

He adds that his second reason is fairly obvious. “He is the last man to walk on the Moon and we haven’t been back in over forty years. As time has gone by, that has become more and more significant.”

| “There were some great astronauts who went to the Moon and who were incredibly gifted at flying those pioneering space machines, but not all of them were particularly charismatic or engaging characters,” Craig said. |

The access the production team was granted was unprecedented, and it was Cernan’s eventual willingness to tell all once he knew the film wasn’t about eulogizing him, that makes it so impressive. Dodds notes of Cernan, “He’s the real deal, a leader of men. Obviously we were making an objective film but the whole crew became very fond of him. Once he bought into the idea he was a dream to work with.” He adds that once Cernan was persuaded that this was a project worth pursuing everything fell into place. “Getting Gene on board was the tough thing. He was cautious about getting involved at first, but once he did it was all-in. We were lucky from that perspective.”

Cernan’s former NASA colleagues Jim Lovell and Alan Bean are among those involved, and some of the more emotional moments involve Cernan’s immediate family, as well as Martha Chaffee, widow of Roger, one of three Apollo 1 astronauts killed in a fire on the launch pad in a test at Kennedy Space Center (KSC) on January 27, 1967. Craig admits, “We actually had access to more friends and family than there was room for in the film. There are half a dozen interviewees, great Navy buddies for example, that there was no room for, especially in the lean 95-minute cut.” One humorous addition is that of Fred “Baldy” Baldwin, a long-time friend and fellow Navy fighter pilot, who Dodds says helped humanize Cernan in the film. “He’s like that best friend that brings you back down to Earth, even if you’ve been to the Moon!”

The author (center) with producer Gareth Dodds (left) and director Mark Craig at Jameson Film Festival in Dublin in March. (credit: Shane Hannon) |

One highlight is the use of an observational style of filming, with Cernan left to his own devices at places like Arlington National Cemetery and Pad 39A at KSC. The film crew would retreat to a certain distance away, leaving just a radio mic on Cernan, allowing some truly special and heartfelt moments to be captured. This desire to take Cernan back to the actual locations of key events in his past is another major plus.

For example, bringing Cernan back to the Nassau Bay community on the southeastern edge of Houston where he and other astronauts lived during the Apollo Program brought out emotions that simply would not have spilled to the surface if the film was merely narrated from a place of little significance to the overall story. The film allowed Cernan the opportunity to return to the KSC launch pad and astronaut quarters, a poignant visit that features prominently in the film’s official trailer. Craig says, “It was the first time Gene had been back there [to the launch pad and crew quarters specifically] since he launched in 1972. In a funny way it hasn’t changed an awful lot. A lot of the décor is exactly the same as it was in 1972.”

In terms of archive footage, the film contains clips and images that even the most ardent space buff will not have seen before. Dodds said, “NASA have digitized a lot of their archives, we had access to that, but there were also catalogues that list everything that’s there. So basically we were interested in everything under the name ‘Cernan.’” The film’s diligent archive researcher, Stephen Slater, does not disappoint in terms of rare content. The visual effects are also remarkably stunning, with a CGI depiction of Cernan’s now-infamous “Spacewalk from Hell” on Gemini 9A in 1966 particularly impressive. One would assume the visual effects side of the film was orchestrated by some big Hollywood company, but it was in fact a group of animation and digital enterprise staff and students at Teesside University in Middlesbrough, England, who brought the spacewalk back to life for our viewing pleasure.

| “It was the first time Gene had been back there [to the launch pad and crew quarters at KSC specifically] since he launched in 1972. In a funny way it hasn’t changed an awful lot. A lot of the décor is exactly the same as it was in 1972.” |

The film has been doing the festival circuit ever since its world premiere at the Sheffield Doc/Fest in June 2014. As well as the March showing at Dublin’s Savoy cinema for the Jameson Dublin International Film Festival (JDIFF), the film has also enjoyed screenings in Toronto and Sarasota, among other places. It truly is a film that is made for the big screen, and Lorne Balfe’s stirring score will add the complimentary chills down your spine. A recent screening at the US Capitol in front of top government officials and the head of NASA left the audience highly impressed, while the film also won the Audience award at the Newport Beach Film Festival in California.

In terms of a distribution deal, Dodds said, “After SXSW there are several interested parties, which is a good place to be in. We’d imagine fairly soon there’ll be an announcement to make.” The United States, possessing the biggest potential market, will likely serve as the starting point for any theatrical release in the future. Craig said, “As you can appreciate, there are different territories around the world and we have to do things in a particular order and so it’s potentially quite complex, but we should have news on everything very soon.”

Mark Craig recalled growing up in the Apollo era as a kid. “I was very much of the mind, as a lot of kids in my generation were, that going into space would sometime be an accessible thing that we could do one day in the future,” he said. “It didn’t quite pan out that way, but we could dream at least.” It is that same dreaming, perhaps of World War Two hero fighter pilots and soaring above the clouds, which led a kid from outside Chicago, born not 31 years after the Wright Brothers first powered flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, to walk, drive, and temporarily live on the Moon in his own lifetime. Orville Wright was 32 years of age when he made that first 12-second flight on December 17, 1903, the very same age Gene Cernan was when he made his own first flight into space in 1966.

In 100 years’ time, long after Gene Cernan and the other Apollo astronauts, not to mention all those reading this, have gone and, to quote John Gillespie Magee’s Aviator’s Poem, “slipped the surly bonds of earth,” The Last Man on the Moon will continue to inspire through the medium of film. Perhaps a child alive today, or even a child of theirs a generation down the line, will watch this extraordinary story on the big screen and be inspired to follow in Cernan’s eternal footsteps. Perhaps that very child will go on to take mankind’s next steps on another heavenly body. Perhaps the flag they raise will represent all of humankind, and perhaps the very dust they walk on will not be gray, but red.