Impatience for Marsby Jeff Foust

|

| “It is my firm belief that we are closer to getting there today than we’ve ever been before in the history of human civilization,” Bolden said. |

Bolden, in his speech, mentioned the address President Obama gave in April 2010 at the Kennedy Space Center, calling for humans to Mars orbit in the mid-2030s and landing shortly thereafter. “There is a new consensus emerging around this timetable, and this around this goal,” he said. “There is also a consensus emerging around NASA’s plan for going there. This plan is clear. This plan is affordable. And, this plan is sustainable.”

While there may be a consensus around NASA’s goal and schedule, there’s less consensus about what that plan should be, in part because details on how to get there in the 2030s, from where we are today, are unclear, and sometimes deliberately so by NASA. That’s created an opportunity for others to step in and offer their ideas on how to get humans to Mars.

Seeking an executable strategy

NASA has, for now, held off on developing a detailed approach for getting humans to Mars, despite pressure from various quarters, from Mars mission advocates to members of Congress. The agency’s last detailed mission design, called Design Reference Architecture version 5, was last updated in 2009, when NASA was still pursuing the Constellation program.

An update of that architecture is not expected any time soon, as NASA focuses on broader issues. “In terms of another design reference mission,” William Gerstenmaier, NASA associate administrator for human exploration and operations, said at a NASA Advisory Council (NAC) meeting last month, “it’s probably years away.”

Some would like to speed up that timetable. Several versions of NASA authorization legislation developed in the House would require NASA to develop a “roadmap” that would lead to humans on the surface of Mars, and then update that roadmap on a regular basis. While some of those bills have passed the House, they have yet to become law.

| “We don’t lack for architectures,” said Naderi. “So, do we really need another one?” |

The Senate plans to work on its own version of a NASA authorization bill in the coming weeks, and it may include some kind of similar direction. “I do think there’s a lot of interest in doing something,” said Nick Cummings, a Senate Commerce Committee staff member, in a May 5 presentation at the Humans to Mars conference. He added the Senate might seek that information through a series of hearings rather than a formal report.

The NAC is also pushing for a more detailed Mars exploration strategy. “The Council finds that developing an executable exploration strategy with plausible costs leading to humans on Mars in the 2030’s would help NASA build the consensus necessary for such a program,” it concluded in a formal finding after its meeting last month.

NAC indicated that while NASA has the goal of sending humans to Mars, it must provide more details. “A long term strategy and corresponding plans must also be developed,” the council’s finding stated. “By this statement, the Council means a set of notional milestones, launches and hardware developments that are sufficiently defined so as to allow a cost assessment.”

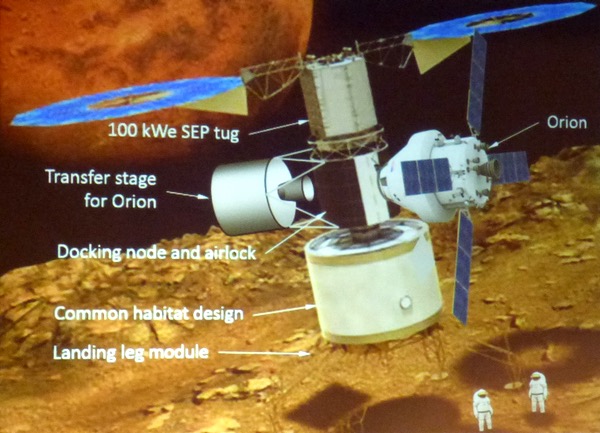

An illustration from a JPL presentation at the conference May 6 of their concept of a Phobos habitat with an Orion spacecraft, transfer stage, and solar electric tug all attached. (credit: J. Foust) |

JPL’s plan

There are, of course, many concepts for human Mars missions. “We don’t lack for architectures,” said Firouz Naderi, director of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Solar Exploration Directorate, in a conference presentation May 6. “There are quite a few of them out there. So, do we really need another one?”

Naderi, not surprisingly, thinks so. He and a small team of JPL developed such an approach that they argue allows for sending humans to Mars orbit—specifically, the moon Phobos—in 2033, with a landing on the Martian surface in 2039. This plan, briefed at an invitation-only Mars exploration workshop last month (see “Doing humans to Mars on—and within—a budget”, The Space Review, April 6, 2015), was publicly presented for the first time at the conference.

One key constraint they used in developing their architecture was budgetary, Naderi said: fitting it within NASA’s current human spaceflight budget, adjusted for inflation. The other, he said, was delivering a Mars mission on a reasonable schedule that would maintain public interest: “Is anybody really going to get excited if I say we’re going to Mars in 2070?”

JPL’s plan, he said, relied on technologies and systems either available today or under active development, like the Space Launch System heavy-lift booster and solar electric propulsion (SEP). They specifically eschewed any “exotic technologies” like nuclear thermal propulsion.

The JPL approach is also an incremental one, which Naderi described using a baseball analogy. “You can always go to the plate trying to hit a home run in one shot,” he said, but run the risk of striking out. The alternative approach is to get a runner on and advance him base by base with hits, walks, stolen bases, and sacrifices. “At the end you score, and it is not any less engaging or exciting to the people in the stadium than it is to hit a home run, and you end up spreading the risk and taking the public along with you.”

That “small ball” approach to Mars exploration uses four SLS launches spread over several years for that initial human mission to Phobos. The first would launch a SEP-powered tug to send to Mars a pair of transfer stages for later parts of the mission. The second would also use the same SEP tug to send a habitat module to land on the surface of Phobos. Those launches could take place years in advance, said chief architect Hoppy Price, taking advantage of the performance offered by solar electric propulsion.

| “We believe Mars is possible and in a time horizon of interest,” Baker said. |

The other two SLS missions would launch close together. One would place into Earth orbit a deep space habitat module and a Mars orbit insertion stage. The other would launch an Orion spacecraft with a four-person crew. The Orion, remaining attached to the SLS’s Exploration Upper Stage, would dock with the hab module, and the upper stage would then boost the stack on a trajectory to Mars, arriving 200 to 250 days later.

Once entering Mars orbit, the Orion would undock with the hab module and rendezvous with one of the transfer stages brought to Mars orbit on the first SLS mission. That stage would be used to dock the Orion to the Phobos habitat, where the crew would stay for up to 300 days. In the meantime, the hab module would dock with the other transfer stage in Mars orbit, which will be used for the return to Earth. At the end of the crew’s time on Phobos, the Orion returns to the hab module, and the transfer stage boosters the stack back to Earth.

A similar approach, Price said, would be used for a “short-stay” Mars landing mission that could be flown in 2039. That approach would require six SLS launches to accommodate the addition of a lander that could support two people on the surface for 24 days. “This first mission would probably be something like Apollo 17 in scope,” he said, likely including a vehicle similar to the Apollo lunar rover.

That architecture could be built upon for future missions, allowing four-person crews to spend up to a year at a time on Mars starting in the mid-2040s, Price said.

JPL made its own cost estimates of that Mars architecture, then subjected them to an independent estimate by the Aerospace Corporation, which had performed similar cost estimates of Mars mission concepts for the National Research Council’s report. That cost model found that the architecture, which includes several test flights in cislunar space and testing of the lander on the Moon, fit within their cost cap if the International Space Station ended in 2024. If the ISS is extended to 2028, Baker said there was a peak a little above the inflation-adjusted budget in the latter half of the 2020s, which Naderi later said was “a couple hundred million” dollars.

“We believe Mars is possible and in a time horizon of interest,” Baker said. “What you need is a clearly articulated strategy, one that allows you to engage stakeholders; a budget adjusted for inflation; and finally, an affordable architecture that allows you to spread the campaign over time into a series of exciting flights and allows you to fit under the budget line.”

Naderi acknowledged that this architecture, developed internally at JPL, was not intended to be the last word on Mars exploration concepts; he said after his talk that they had already started work on a follow-up study to further refine it. It was also unclear how much support the concept had elsewhere in NASA, although Bolden did make reference to it briefly in his speech the day before.

John Baker, Hoppy Price, and Firouz Naderi discuss their Mars exploration architecture at the Humans To Mars Summit May 6. (credit: J. Foust) |

Window of opportunity

NASA argues that while it hasn’t adopted a particular, specific architecture for human Mars missions, it has a general path in place, and deviating from it could jeopardize that mid-2030s goal. “Stay the course, make small course corrections as we go, and we’ll get there,” Bolden said at the end of his conference speech. “If we go back and try to start all over now, we are toast. We are history.”

Others, while not necessarily seeking to start over, do want NASA to put more meat on the bones of its Mars plans, particularly if they can, like JPL’s concept, support early human missions to Mars. “I think we have a window of opportunity to build a consensus for a long-term, cost-constrained, executable humans to Mars program,” said Scott Hubbard, a Stanford University professor and member of the NAC.

| “If you don’t have a plan to use that funding that is clear and is costed and is executable,” Hubbard warned, “other people will make demands for that funding and we will once again be 30 years away from humans on Mars.” |

Hubbard said that window of opportunity is open in part because of “emerging public advocacy” and growing public awareness of, and interest in, Mars exploration, spurred on by things as disparate as Andy Weir’s novel and upcoming movie The Martian and Mars One. (Hubbard is skeptical about Mars One’s prospects, saying founder Bas Lansdorp is “extraordinarily uninformed” about the technical difficulties of Mars missions, but noted the outpouring of public interest in the effort.)

“The bottom line is that there is a new—less than five years old—public interest in humans to Mars,” Hubbard concluded.

Hubbard argued, though, that Mars mission advocates needed to move now to convert that interest into sustained funding through development of a more detailed Mars mission architecture. “If you don’t have a plan to use that funding that is clear and is costed and is executable,” he warned, “other people will make demands for that funding and we will once again be 30 years away from humans on Mars.”

At the conference, there were—not surprisingly—few who objected with sending humans to Mars as soon as possible. Bolden, in his remarks, even got the audience to repeat the phrase “Mars matters” in unison a couple times. “As Martin Luther King Jr. is purported to have said, sometimes it’s important to preach to the choir, otherwise they might stop singing,” Bolden said.

At the end of the conference, though, a retired NASA official warned against doing just that. “This has been a great time for the choir to get reinvigorated. But we need to quit doing this,” said former space shuttle program manager Wayne Hale. “We all agree that going to Mars is great. We all agree that the space program is great. We all agree that this is what we need to go do. But this is not the majority opinion that is held out there.”

That means, he said, going out beyond the small, insular space community to the broader public and convincing them of the importance of human missions to Mars, if the program is sustainable over the long run. “We need to get out of Washington DC and go out into the country,” he said. “We need to stop talking to ourselves.”

That is, in some respects, a task that spans generations, for the engineers and astronauts who will design, build, and fly those Mars missions two and three decades hence are in school today. At the end of his speech, Bolden spotted a young girl in the audience. “Are you going to Mars?” he asked her. Her response, while inaudible, was apparently noncommittal.

“Please say yes,” Bolden said. “We promise we’re going to bring you back.”