A quick look at trade secrets in outer spaceby Kamil Muzyka

|

| The issue of protecting trade secrets poses a serious legal challenge for asteroid mining because it will most likely cause the proliferation of claims echoing the patent interference proceedings. |

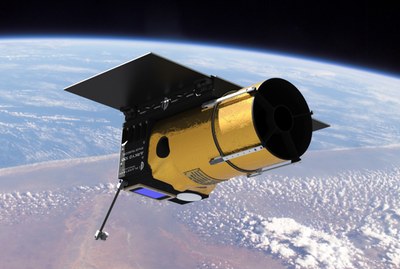

Similarly to seismic1,2 and geological survey data,3 the spectrographic data collected from asteroids via A3R telescopes consists of both intellectual property and trade secrets. A trade secret is defined as “a formula, practice, process, design, instrument, pattern, commercial method, or compilation of information which is not generally known or reasonably ascertainable by others, and by which a business can obtain an economic advantage over competitors, who don’t know how to use it or customers.”4

In the upcoming era of licensed space miners, such “compilation of information” will be of great value, since the ore deposits are beyond any country’s jurisdiction.

Since a legal principles regarding space resource claims5 has you to be developed, the question remains whether a future licensee would be required to provide a comprehensive survey date of the celestial body as part of its licensing application to the licensing authority.

A solution applying the “landers-keepers”6 principle also seems a viable alternative. It would require an on-site survey probe to touch down on the asteroid, thus the license will only mention the right to mine celestial resources from asteroids without limiting it to specific asteroids or space sectors.7 .

In both instances, the issue of protecting trade secrets poses a serious legal challenge because it will most likely cause the proliferation of claims echoing the patent interference proceedings8 like “astrotrolling”9 or “rock stalking.”10

The use of trade secrets is not uncommon the aerospace industry. And in the case where one or more spacefaring parties or launching states fails to respect the competitor’s intellectual property right or its attempts to successfully litigate patent infringement claims are futile, use of trade secrets seems to be the only reasonable weapon against its competitors.11

This applies to both the test data and scientific data consisting of future scientific discoveries and prototypes. In both cases, all details must be fully disclosed so as to enable a person skilled in the art to which the invention pertains to make and use the invention,12 or in the alternative, the details must be sufficiently described in peer review publications.13

So far, protection of trade secrets concerning outer space, space vehicles, automated and telerobotic probes, and private or international space stations remains largely unregulated. To effectively protect trade secrets from its competitors, a party may be compelled to implement special procedures or even special technology.

| So far, protection of trade secrets concerning outer space, space vehicles, automated and telerobotic probes, and private or international space stations remains largely unregulated. |

In the case of A3R or similar asteroid-survey telescopes or probes, this can be accomplished through proper telemetry solutions, such as laser communication with additional secure signal coding. Any type of purposeful signal interception or attempt to hack the relay server would constitute sufficient basis for filing a lawsuit for infringement or industrial espionage in both the US and EU laws.

But that’s not the only problem with protecting trade secret related to the outer space. There is also a salvage problem.

Since at this point regulation of space salvage does not exist, despite some academic models,14,15 such regulations could be derived from the admiralty and maritime law of both the EU and the US.

Although the principles of the EU admiralty law mostly require a bilateral salvage agreement known as the contract salvage, the US admiralty law recognizes the concept of “pure salvage.”16 Under pure salvage, the salvor has the right to file a salvage claim with an admiralty court and to receive a salvage reward without the vessel owner’s consent. The salvor must, however demonstrate that the rescued vessel was in peril of loss, destruction, or deterioration, that the salvor was not under a duty to salvage the vessel, and that the salvage operation was fully or partially successful.

The same principles may be applied to survey probes and telescopes. If, for example, a telescope, which fell out of orbit after a collision with meteorite, is captured by a crewed or robotic ship, then the ship would be able to successfully assert its right to salvage in an outer space admiralty court and receive a salvage award.

But such salvage might interfere with the telescope owner’s legal rights, including its intellectual property rights recorded on drives or embedded in its circuits. One may easily envision a scenario where, by the time the salvaged device is returned to its rightful owner, the salvor may have gained access to the proprietary data, and thus undeservingly gaining competitive advantage in the asteroid mining industry, or even selling the recovered proprietary information to the highest bidder.

Such recovery of proprietary information actually occurred in real life during the Cold War, when the USA preformed a covert salvage operation of a sunken soviet K-129 submarine. Acting under the guise of a deep sea drilling, USNS Hughes Glomar Explorer embarked on recovery mission, currently known and disclosed as Project Azorian. Although full recovery of the submarine was unsuccessful, the effort did recover codebooks and armament subsequently examined by the CIA.

Since similar actions can be conducted to misappropriate trade secrets,17 the perpetrator may be sued for conducting industrial espionage. Examining the interiors and mechanisms or parts of spaceships, satellites, probes and stations by the “salvor in possession” doesn’t fall under the lawful reverse engineering category.

In the current legal environment there are no foolproof means of protecting trade secrets simply because the very process of litigating misappropriation of trade secrets may lead to their partial of full disclosure.

| Through a presalvage contract and insurance, the owner of a spacecraft, probe, or any crucial space equipment may designate a specific party to salvage its wreck or derelict. |

As a preliminary step, the plaintiff must establish that the information is sufficiently secret, that the plaintiff derives value from the information’s secrecy, and that it has taken reasonable steps to maintain the information’s secrecy. The trade secret owner must than prove that its trade secret was misappropriated by the defendant and used in the defendant’s business. Although the plaintiff may seek protective order, it will have to identify the trade secret specifically during litigation.18 As the old Roman rule goes, Actori incumbit probation.19

Despite the fact that every vessel and craft in outer space is treated as an extension of the land of the state of registry,20 and thus, every form of intellectual property seems to be protected by the laws of the those states, these laws do not guaranty protection against theft or IP piracy.

As the examples from maritime salvage indicate, the entity that salvages a whole spacecraft or its part will keep it in its possession until properly awarded by its owner, after filing a salvage claim. Thus, nothing prohibits a third party with proper skills and equipment to “hunt” for wrecks and derelicts.

However, this could indeed be a solution to the problem of IP theft during salvage operations. In order to make a salvage claim, the salvor must be in physical possession and control over the wreck. The salvor in possession, however, must also show that it is not only in physical possession of the salvaging object, but also is carrying out ongoing operations in order to fully recover such wreck.21

By a way of countermeasure, through a presalvage contract and insurance, the owner of a spacecraft, probe, or any crucial space equipment may designate a specific party to salvage its wreck or derelict.

By permanently installing an emergency beacon of the designated emergency salvage company on its spacecraft prior to its launching, the owner will ensure the precontracted emergency salvor the title of “salvor in possession”, which will prevent unauthorized salvors from attempting to salvage or intercept them. In case of an emergency, the beacon sends properly coded signals to the salvage company's HQ, which automatically files a salvage claim to the proper outer space admiralty court. The contract with the designed emergency salvor should of course contain a confidentiality of non-disclosure clause.

In conclusion, the evolution of law is based on the same principle as evolution of life: continuous adaptation to new and changing environments. In the cold and unforgiving environment of space mining and exploration, the industry cannot afford to wait for national or international legislatures to devise an adequate solution guaranteeing protection of intellectual rights in space. It is up to the legal departments of the space companies to ensure that their intellectual property rights or trade secrets are adequately protected by means that are in step with ever-evolving technology.

Endnotes

- Doug Rhorer “Oil Field Confidential: Protecting Seismic Data and Other Trade Secrets”

- Steve Borgman “Keeping Trade Secrets In The Texas Oil Patch”

- Jan A. Stefanowicz “Access to geological information and its protection”

- Tom C. W. Lin - Executive Trade Secrets, 87 Notre Dame Law Review (2012) available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol87/iss3/1/

- US High Sea fishing practice differs from the one settled by United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea signatories.

- Derived from the finders keepers principle: http://www.rubinfiorella.com/pdf/5-1-2009.pdf

- Similar to the US High Sea Permits: http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/ia/permits/highseas.html

- Linda R. Cohen. Jun Ishii “Competition, innovation and racing for priority at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office”

- Launching swarms of claim markers, beacons or on site probes in order to gain as much asteroids as one can, enforcing subcontracts on other mining companies.

- Keeping mining ships on standby in close proximity to the belt, while actively leeching spectrographic data in order to gain the upper hand in the race towards a resource rich asteroid.

- As Elon Musk, the CEO of SpaceX, stated in an interview for Wired magazine: “We have essentially no patents in SpaceX. Our primary long-term competition is in China—if we published patents, it would be farcical, because the Chinese would just use them as a recipe book”.

- The enablement requirement: http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2164.html

- Daniel Fehder, Fiona Murray, Scott Stern; “Intellectual Property Rights and the Evolution of Scientific Journals as Knowledge Platforms”

- N. Jasenruliyana “Regulation of Space Salvage Operations: Possibilities for the Future”

- Wayne N. White, Jr. “Salvage Law for Outer Space”

- Keith S. Brais, Esq. “Marine salvage at a glance”

- Melissa K. Force “Protecting Space Technology Through Trade Secret Law”

- “Understanding and litigating trade secrets under Illinois Law: An Outline For Analyzing The Statutory And Common Law Of Trade Secrets In Illinois”

- “The (burden of) proof weighs on the plaintiff”

- Resolution adopted by the General Assembly: 3235 (XXIX). Convention on the Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space.

- RMS Titanic, Inc. v. Wrecked & Abandoned Vessel