A midsummer classicby Jeff Foust

|

| “It’s always heartstopping when you lose that carrier lock with your spacecraft,” said Bowman. |

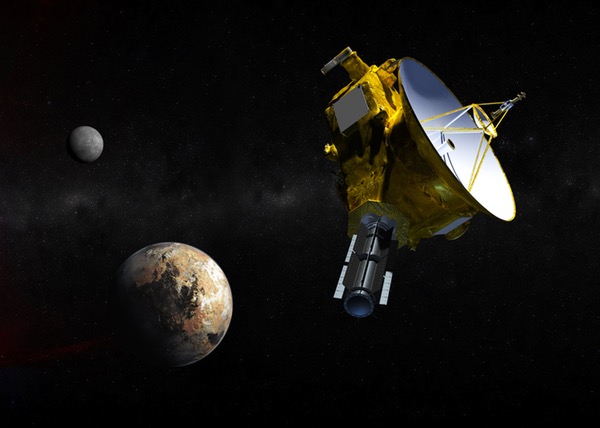

But as the game progresses in Cincinnati, the real midsummer classic will be taking place hundreds of kilometers to the east, on the campus of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL). Shortly before 9 pm Eastern time Tuesday night (0100 GMT Wednesday), the New Horizons mission team there will be listening for a transmission due from the spacecraft, the first communications since the spacecraft made its closest approach to Pluto thirteen hours earlier. If New Horizons does phone home, and in good health, the excitement in that mission operations center will likely be far greater than anything on the baseball diamond.

An “Apollo 13” moment

In some respects, the New Horizons mission has already been exciting—a little too much so. Late July 4, NASA announced that New Horizons had gone into a protective “safe mode” earlier than day. There’s arguably never a good time for a spacecraft to go into safe mode, but this was a particularly bad time, since New Horizons was days away from beginning the encounter phase of its mission, leading up the July 14 flyby.

Initially, like the spacecraft itself, information was only coming out slowly from the mission about the incident. By July 6, though, project officials said that the anomaly was resolved and the spacecraft ready to resume science observations, just in time for the flyby.

The problem, according to mission manager Glen Fountain at APL, was that the spacecraft’s primary spacecraft became overloaded. Controllers had transmitted a detailed series of instructions, called a “command load,” for the spacecraft to carry out during the encounter. The spacecraft, after receiving the instructions, loaded them onto its flash memory.

That was taking place at the same time, though, as it was compressing data also stored on flash memory of previous observations that would not immediately be transmitted back to Earth, freeing up memory for data to be collected in the flyby. “The computer was trying to do these two things at the same time, and the two were more than the processor could handle at one time,” he said during a July 6 news briefing.

The spacecraft, he said, did exactly as it should have: it went into safe mode and switched to a backup computer, which started transmitting diagnostic data back to Earth. Nonetheless, the sudden loss of communications, if only for less than 90 minutes, was initially worrisome. “It’s always heartstopping when you lose that carrier lock with your spacecraft,” said Alice Bowman, the New Horizons mission operations manager, in a July 12 briefing at APL.

The team worked continuously throughout the day July 4 and into July 5 to diagnose the problem and work out a way to correct it. Alan Stern, the mission’s principal investigator, said he had already been his office on the APL conference since 4 am when the anomaly took place. “I stayed until about 5 am in the [next] morning. The engineering team didn’t leave,” he said.

That engineering team was able to quickly determine the spacecraft became overloaded because it was writing and compressing data simultaneously. They took the spacecraft out of safe mode on July 5 and switched back to the primary computer, but waited until the command load for the nine-day encounter period started on July 7 to resume science observations.

At the July 6 briefing, officials said they did not expect a similar event to take place again. The spacecraft would not be simultaneously receiving commands and compressing data throughout the encounter phase of the mission. Moreover, during encounter phase, the ability to go into safe mode is disabled if there is an anomaly, with the spacecraft instead instructed to switch to a backup computer and request help while continuing to carry out commands. “I’m quite confident that this kind of event will not happen,” Fountain said.

The safe mode did disrupt nearly three days of science observations. Stern, though, minimized that loss because the spacecraft was still more than ten million kilometers from Pluto at the time of the incident. ““Our assessment is that the weighted loss is far less than one percent,” he said July 6. “We can say there is zero impact to the ‘Group One,’ or highest priority science.”

| “The team rose to the occasion and overcame the challenge that they had,” Fountain said. “It’s how we rose to the occasion, how the team rose to the occasion, that is like Apollo 13.” |

At that July 6 briefing, Stern and Fountain played down the significance of the event: yes, the spacecraft went into safe mode, but the team worked as it needed to, resolved the problem, and got New Horizons working again with a minimal loss of science. A later Washington Post article, though, suggested a more serious incident, with Stern calling the anomaly “our Apollo 13.”

Asked about that July 12, Fountain initially seemed uncomfortable with that assessment. Later, he argued that there were both differences and similarities with Apollo 13. “The incident that happened, the anomaly, happened at a time where it didn’t affect the mission results,” he said of the New Horizons safe mode. “We are slated to get all the data that we promised to deliver to NASA for the mission. That’s how it’s different from Apollo 13.”

There were similarities, too, he acknowledged. “The team rose to the occasion and overcame the challenge that they had,” he said. “It’s how we rose to the occasion, how the team rose to the occasion, that is like Apollo 13.”

New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern talks with reporters at APL on July 12. (credit: J. Foust) |

Flyby, then “raining data”

New Horizons has been carrying out that “encounter load” of commands since July 7, doing a series of observations with its various instruments and returning some of them to Earth. For the last several days, the mission has released images of increasing resolution and clarity of Pluto and its largest moon, Charon. Images released late July 12 showed what appeared to be cliffs on Pluto’s surface, and a chasm on Charon longer and deeper than the Grand Canyon.

The last data New Horizons will send before its closest approach will be at 11:17 pm Eastern time July 13. During the close approach itself—the spacecraft passes 12,500 kilometers from Pluto at 7:50 am July 14—the spacecraft will be busy collecting data. That silence will continue throughout the day, creating an odd anticipation back on Earth for an event that will have already happened.

The first opportunity for the mission team, and everyone else, back on Earth to hear from New Horizons will be the evening of July 14. A brief, 15-minute transmission is planned, scheduled to arrive at Earth at 8:53 pm Eastern. That will be primarily a check on the health of the spacecraft, and not scientific data.

“It’s not anything that’s been recorded by the recorders on board,” Bowman said. Instead, the spacecraft will go through several cycles of real-time spacecraft telemetry. “We will learn, in a general sense, if the spacecraft is healthy,” she said. That includes whether there were any anomalies during the flyby, as well as how much data is stored in the spacecraft’s recorders. That will indicate how well the spacecraft carried out its scientific observations during the closest approach.

“If everything looks normal,” she said of that initial downlink of data, “there’s absolutely no reason to believe that we didn’t collect the goods.”

Chris Hersman, mission system engineer on New Horizons, said people watching the team in the mission operations center that evening should be able to know that the signal arrived. “Sometimes, when people are looking at their screens, their reactions are a little bit not quite so emotional,” he said. “I’m sure on Tuesday night it will be obvious.”

Assuming that telemetry does arrive Tuesday night, and indicates the spacecraft is healthy and its recorders filled with data, transmissions will begin on Wednesday the 15th. “On Wednesday, it starts raining data,” said Stern. The mission will hold a press conference that afternoon with some of data, just a few hours after its return to Earth, “hot off the DSN [Deep Space Network],” he said.

That rain, though, may seem a little more like a trickle. Given the spacecraft’s distance and limited power, data rates are low: about two kilobits per second, about the speed of a computer modem from a quarter-century ago. At those speeds, it will take more than a year for New Horizons to return all of its flyby data.

“We’ve cherry-picked out what we think is some of the best data that we’ll be sending back in the next couple of days” after the closest approach, project scientist Hal Weaver said July 12. “But we’ll really have to wait until later in the year and the following year after that. The science team is going to be having a surprise every day as we send the data down over the course of the next year.”

At the same time as scientists pour over the data that comes back, the mission will be laying the groundwork for a potential second act. The mission has been looking for Kuiper Belt objects (KBOs) that the spacecraft could fly past after completing the Pluto part of its mission: another opportunity to study this population of icy bodies on the fringes of the solar system.

| “I mean, how often—once in a lifetime?—do you get this chance?” Fountain asked. |

That search has turned up two potential candidates, both of which New Horizons could fly by in 2019. To do so, though, requires doing a maneuver later this year to put the spacecraft on course for it. A decision on which KBO to fly past is expected in August, with the maneuvers themselves—a series of four to five thruster burns, each similar in size to previous spacecraft maneuvers, Hersman said—planned for late October and early November.

A decision on whether to actually carry out the flyby, which will require additional funding for an extended mission from NASA, won’t come until next year. Jim Green, head of NASA’s planetary sciences division, said July 12 that decision would be made next year as part of the agency’s biannual “senior review” of ongoing planetary science missions.

“If it reviews well, that’s one part of the approval,” he said. An extended mission would also require sufficient funding in NASA’s budget to pay for it, regardless of its scientific merits, as well as “programmatic decisions” for the mission. “That whole process will take a year,” he said, with a decision coming in August or September 2016.

That future KBO flyby, though, isn’t exactly a pressing issue right now. “I’d be willing to bet that the team is not focused on that at the moment,” Green said.

Instead, the focus in on the here and now, that flyby Tuesday that promises are best look yet, and likely for many years to come, at the former ninth planet. Fountain said he’s advised his team Tuesday to live in the moment for this historic flyby. “I mean, how often—once in a lifetime?—do you get this chance?” he asked. “It’s a wonderful time to be alive and to be aware of what’s going on, to realize that you’re participating in something much larger than yourself.”