The International Code of Conduct: Comments on changes in the latest draft and post-mortem thoughtsby Michael J. Listner

|

| One addendum drops any pretense that the Code is not designed to promote arms control as one of its ideals. |

These procedural actions occurred against a less than optimistic backdrop for the Code as the prospects of the Code’s adoption going into the meeting were slim. This pall over the Code was exacerbated by the competing interests and input from more than 100 countries invited to the meeting, and was also overshadowed by the continued rejection of the Code by both the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China (PRC).2

Aside from the procedural maneuvering, which in effect invalidated the purpose of the meeting, the March 31, 2014, draft of the Code contains significant changes from the September 16, 2013, draft. This essay will examine four of these changes and discuss the Code in general, including concerns moving forward and whether adopting the Code continues to be in the national interests of the United States.

Analysis of key changes in the March 31, 2014, draft

At first blush, the latest draft of the Code is one page longer than the September 2013 draft. A closer look at the Code reveals important changes that affect not only the intent of the Code but its scope as well. Two such additions are found in the Preamble3 opening with Box 6, which references the Prevention of Arms Race in Outer Space (PAROS) and states, “Noting the importance of preventing an arms race in outer space.”

This addendum drops any pretense that the Code is not designed to promote arms control as one of its ideals as well as the interests of the arms control community.4 What is more, the language of Box 6 also gives an implicit nod to the vacuous issue of “space weapons” and appears to offer a conciliation to Russia and China, both of whom have refused to endorse the Code. The Preamble continues with an arms control theme in Box 15:

Without prejudice to ongoing and future work in other appropriate international fora relevant to the peaceful exploration and use of outer space such as the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space and the Conference on Disarmament;5

In essence, Box 15 recognizes the continuing work on PAROS and the proposed PPWT space arms control treaty, and provides an assurance to their sponsors the Code is designed to neither affect nor supplant either of the proposed accords. This has the effect if not to persuade China and Russia to endorse the Code, then to at least assure both nations that an implemented Code would not interfere with their plans in the Conference on Disarmament.6

The next significant change in the latest draft of the Code is found in the “Purpose and Scope” section of the Code. Specifically, Section 1.1 of the Code states:

The purpose of this Code is to enhance the safety, security, and sustainability of all outer space activities pertaining to space objects, as well as the space environment.

Noteworthy in this section is the term “space object,” which is not given any definition by the Code, but appears to resemble to the term “space object” used in the Rescue Agreement. The term “space object” is defined in Article I(d) of the Liability Convention:

The term “space object” includes component parts of a space object as well as its launch vehicle and parts thereof.7

The definition of “space object” in the Liability Convention is for purposes of that Convention only, but absent a specific definition in the Code, it is reasonable to believe a similar usage would apply.8

The final and most significant change is found in Section 1.4, which relates to the non-binding nature of the Code. Consider Section 1.4 of the September 16, 2013, draft of the Code, which states:

Subscription to this Code is open to all States, on a voluntary basis. This Code is not legally binding.

By comparison, the March 31, 2014 draft reads Section 1.4 as follows:

Subscription to this Code is open to all States, on a voluntary basis. This Code is not legally binding, and is without prejudice to applicable international and national law.9

Section 1.4 asserts the non-binding, non-legal nature of the Code, which in the case of the United States means the Code would not be regarded as having the force of a treaty and therefore inferior to existing federal law. What is more, the “without prejudice” language in Section 1.4 takes language from Article 2(2) of the Vienna Convention10 and appears to be designed to ensure the position of states in regards to their internal laws and usage, and specifically, laws relating to the ratification of treaties and other international agreements would not be affected by a subscription to the Code. More importantly, Section 1.4 would appear to ensure the national law and domestic usage of how customary international law is created would not be affected by subscription to the Code.11

| So the question is, apart from the non-binding, non-legal nature of the Code, does Section 1.4 by inference include the tenet that the subscribing states would regard the Code as controlling? |

Additionally, Section 1.4 gives the impression to assure states subscription to the Code would not affect the international treaty process of negotiation and acceptance whether through signature, ascension or ratification, but more critically Section 1.4 appears to limit the effect of the Code on the current body of international space law, including the Outer Space Treaty and its progeny to include the creation of customary usage. This is important because the Code mimics specific legal obligations under the current body of international space law, including Article IX12 of the Outer Space Treaty. Otherwise, the Code might be perceived to affect existing treaties and customary law.

Section 1.4 does leave the question open about whether the Code is intended to be controlling. A treaty or an international agreement requires an intention to create legal obligations and rights for it to be legally binding, and without such an intent the agreement is said to be sans portée juridique or without legal effect.13 As noted, Section 1.4 of the Code expressly states the Code is not legally binding, which means the subscribing states would consider the Code sans portée juridique and therefore not engage their legal responsibility, including liability or sanction for non-compliance. That being said, the Code falls into the category of a political or “gentlemen’s agreement”, and as such the Code is not governed by international law and there are no applicable rules pertaining to compliance, modification, or withdrawal until and unless a subscribing state to the Code extricates itself from its “political” undertaking, which it may do without legal penalty.14 However, even though the Code is sans portée juridique, it does not mean a subscribing state to the Code cannot be held accountable for non-compliance.

A subscribing state to the Code will have given a promise to honor its commitments, and the other subscribing states to the Code would have reason to be concerned about compliance with such undertakings. Normally, if a nation disregards a political commitment within a “gentlemen’s agreement” like the Code, it would be subject to an appropriate political response. However, if the subscribing states regard the Code as controlling and authoritative they may rely to their detriment on the political promises made as long as a state subscribes to it, which could subject a subscribing state to estoppel or another equitable remedy for non-compliance.15

So the question is, apart from the non-binding, non-legal nature of the Code, does Section 1.4 by inference include the tenet that the subscribing states would regard the Code as controlling? If Section 1.4 infers the Code is controlling despite its status as sans portée juridique, this could explain the misconception by some proponents a subscribed-to Code would create customary international law.16 More to the point, if the Code is intended to be authoritative and controlling, then unintended consequences could ensue for subscribing states if the political promises within the Code are implemented.

Interrelated to the question of whether or not Section 1.4 intends for the Code to be controlling is the question of conflict of laws. In the case of the United States, an enacted Code would not affect federal statutes as the nature of the Code makes it inferior to federal statutes and would not require Congress to pass federal statutes to act in accordance with the provisions of the Code. However, the Executive Branch, through its subordinate agencies, could try to use federal regulation to bring about domestic compliance with an enacted Code.17 The question in that case is not only whether the Code is controlling, but whether that control requires a nation like the United States to alter its internal regulations to conform to it, and if it does, to what extent if any does the “without prejudice” language in Section 1.4 negate any control the Code might have over domestic regulations?

Another concern related to Section 1.4 is the issue of interpretation. Article 31 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties lays out the general interpretation of treaties. However, non-binding political or “gentlemen’s agreements” like the Code were intended to be excluded from the Convention because they are not governed by international law, which means Article 31 is not automatically implied to be binding to interpret the Code.18 Moreover, neither Section 1.4 nor any other provision of the Code expressly states what benchmarks will be applied to interpret the Code, which could be detrimental to resolving ambiguous political commitments in the Code, unless ambiguities are meant to be resolved by a consensus of the subscribing states. This is in itself is not a solution to the interpretation issue because consensus does not imply an reasonable, never mind favorable, outcome for a subscribing state.19

Post-mortem thoughts

So where does the Code go from here? Bringing the Code under the umbrella of the UN has invited procedural complications that have placed it in bureaucratic limbo. Considering the procedural collapse that occurred when UN patronage of the Code’s negotiation was suggested, it is questionable whether a future resolution to allow the Code to be negotiated with its benefaction will be successful. Yet, beyond whether the Code can be revived in the forum of the UN is the uncertainty regarding whether it is in the interests of the United States to continue to support the measure.

The Code is a transparency and confidence-building measure (TCBM).20 TCBMs are part of the legal and institutional framework supporting military threat reductions and confidence building among nations. TCBMs are recognized by the UN as mechanisms that offer transparency, assurances, and mutual understanding among nations and they are intended to reduce misunderstandings and tensions. TCBMs also promote a favorable climate for effective and mutually acceptable paths to arms reductions and non-proliferation. While TCBMs promote transparency and assurance between nations, they do not have the legal force of treaties, and states entering into them are bound only by a code of honor to abide by the terms of the instrument.21 They are considered a top-down approach to addressing issues: they are not intended to supplant disarmament accords but are intended as a stepping stone to legally-enforceable instruments. As seen with some parts of the Code, TCBMs can also address space activities outside of those performed by the military or those performed for national security reasons.22

| Adopting the Code could coopt the otherwise successful efforts of USSTRATCOM in space situational awareness and arguably create a heavier burden for USSTRATCOM by mandating, through political promises, to provide data that it is already being provided proactively through separate agreements. |

The nature of TCBMs makes it obstinate for proponents to claim the Code is not being used towards an arms control end. Such a claim is akin to saying a tiger is no longer a tiger because it covered its stripes even though it still has all its teeth. Similarly, even though the Code attempts to cover its stripes with the veil of promoting outer space security, by its nature it still has its teeth as a precursor to an arms control/non-proliferation agreement like PAROS, the PPWT, or a similar legally-binding agreement, whether by treaty or executive agreement.

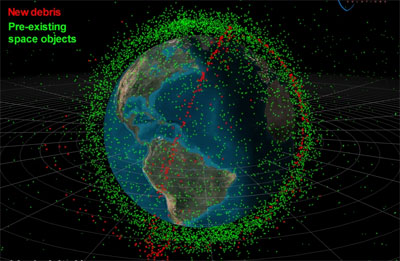

Aside from the concerns of the nature of TCBMs, the Code incorporates political promises that are duplicative of efforts undertaken by the United States. For instance, the issue of orbital space debris is a substantial focus of the Code, specifically in Section 4.It would require a subscribing state to refrain from actions that could create orbital space debris, to take appropriate measures to minimize collisions, and to implement the UN Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines, which were endorsed by the United Nations in General Assembly Resolution 62/217 in 2007. Considering the impact and potential future threat of orbital space debris, this a valid set of principles to promote.

The United States has already taken the lead in orbital space debris mitigation and implementation of mandatory practices. NASA developed orbital debris mitigation guidelines in 1995 and, two years later, developed Orbital Debris Mitigation Practices. These practices became mandatory under the administration of George W. Bush and the 2006 National Space Policy through NASA Procedural Requirement 8715.6A, and the Obama Administration went one step further by extending this requirement to the Department of Defense in 2010. Comparatively, the United Nations adopted its voluntary guidelines, which are heavily based on the guidelines established by NASA, in 2007. If one of the goals of the Code is to compel subscribing states to abide by the UN’s orbital space debris mitigation guidelines, then by adopting the Code the United States will be promising to abide by guidelines and practices it created and voluntarily mandated beforehand.

Beyond the issue of orbital space debris mitigation, the United States provides space situational data, including orbital telemetry for space objects and issues notifications for potential collisions. This information is provided by US Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM) and its Joint Space Operations Center, which is also engaged in creating bilateral transparency and confidence-building measures with other nations, including Russia, for sharing of space situational awareness data.23 One of the objectives of the Code appears to be to increase cooperative sharing and space situational awareness, but that objective is duplicative of what the United States is already doing proactively through bilateral agreements. Therefore, adopting the Code could coopt the otherwise successful efforts of USSTRATCOM and arguably create a heavier burden for USSTRATCOM by mandating, through political promises, to provide data that it is already being provided proactively through separate agreements. In the best case this is redundant, but in the worst case it could implicate sensitive national security information and methodologies and require that information be disseminated without vetting whether the recipient subscribing state has a genuine need for that information or seeks the information for its own geopolitical purposes.

There is also the question how the Code could change after it is implemented. Section 8.1 of the Code allows for modification after it is entered into. This opens the possibility the United States could be enticed into signing onto the measure, which could lead to burdensome political requirements not included in the original document. The allowance for open modification could give other subscribing states the opportunity to gain leverage under the guise of “cooperation” to influence the space policy of the United States to benefit their own geopolitical interests. This means the United States could be in the position of making unfavorable compromises far in excess of what other spacefaring or non-spacefaring nations are willing to make, and could be required to forfeit information, which could damage national security.

More to the point, the Executive Branch’s authority over the implementation of the Code would allow it to make unilateral decisions with regards to compliance in lieu of withdrawing from the Code, which could include compromises purely for political expediency and to create the optics of cooperation, even though those compromises could implicate outer space capabilities and national security interests. Furthermore, if the Code turned out to be controlling and political commitments and later modifications proved burdensome to the interests of the United States, the question is would the Executive Branch exercise the option to withdraw or continue on with the Code strictly out of political expediency?24

Conclusion

Subscribing to the Code would lead the United States to fritter away its advantage in outer space capabilities. Clearly, if the United States subscribed to the Code it would create the illusion of “cooperation” and fulfill the ideological imperatives for practitioners of critical geopolitics. However, it may well benefit the geopolitical interests of other spacefaring and non-spacefaring nations, including geopolitical adversaries who would not subscribe to the Code. The practical effect is the United States could gamble away its advantage in outer space capabilities for the sake of a political agreement that would do little more for the United States than act as a token political victory and provide favorable political optics. The subsequent erosion of America’s advantage in the high ground of outer space would create a more dangerous and unpredictable situation for all space actors, which is converse to the stated moral ideal of the Code.

| At this juncture, the Code appears to be dead, and it is unclear whether it can or if there is a desire to revive it. |

Proponents of the Code will counter the Code is not the potentially damaging tiger that it is and argue that opponents of the Code do not offer an alternative solution to address outer space security. This argument admits the Code is not the best solution but at the same time infers it is better to have a bad solution than no solution at all. In reality, there are pragmatic alternatives to the top-down approach of the Code, but they require the sacrifice of critical geopolitics and its supporting ideologies to a pragmatic bottom-up approach, which is will continue to be unpalatable for many.

At this juncture, the Code appears to be dead, and it is unclear whether it can or if there is a desire to revive it. Should it be revived, soft-power maneuvering and misinformation about the intentions of the United States and the use of its advantage in outer space will continue to be advocated by geopolitical competitors. They will continue to try and lull the giant to sleep through international measures and maneuvering so it can be subdued. In the backdrop of this geopolitical stratagem, those on Capitol Hill who are concerned about the Code, as well as other interested parties, should remain vigilant lest, like a bad zombie movie, the Code reanimates from its grave in the UN and threatens to take a bite from the outer space capabilities of the United States.

Endnotes

- See Tommaso Sgobba, IAASS Statement On International Code of Conduct for Outer Space Operations, Space Safety Magazine, August 5, 2015.

- Both the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China continue to promote their draft Treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space, the Threat or Use of Force against Outer Space Objects (PPWT) in the United Nations Conference of Disarmament. The original draft of the PPWT was presented in 2008 and an updated draft was presented on June 10, 2014, two weeks after the European Union (EU) completed their third Open-Ended Consultations (OEC) for the development of the International Code of Conduct for Outer Space Activities (ICoC) in Luxembourg at the end of May 2014. The latest draft of the PPWT was rejected by the United States and other nations, but the proposal, along with the Prevention of Arms Race in Outer Space (PAROS), still remain the cornerstone of the Russian Federation and PRC’s soft-power strategy, which addressed “space weapons” to assure outer-space security.

- In simple terms, the preamble in an instrument states the reasons for and underlying understandings of the instrument’s drafters and adopters. In the context of legally-binding international instruments it also used to help interpret the meaning of terms and provisions within the instrument. See Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, Article 3(2).

- The tack of the Code towards arms control is not a subjective viewpoint. The annotations note the language of Box 6 make a reference to PAROS. In addition to that reference, the suggestion was made by participants to reinforce the language of Box 6 by adding the phrase “as well as refraining from actions that may lead to a militarization of outer space”. It was further proposed by some participants to include language around legally binding arrangements, and some participants recommended to draw from language from the Group of Government Experts (GGE) when referring to PAROS. Apparently, these further suggestions were not included in this draft, but that does not preclude them from being included in future drafts if the Code is resurrected.

- Without prejudice as used in this context means the provisions of an implemented Code would not be used to interpret or otherwise affect the ongoing efforts in the Conference of Disarmament, which infers PAROS and the PPWT.

- The annotations to the March 31st draft note one of the participants opposed the reference to the Conference on Disarmament. The annotations do not say who that participant was.

- The Austrian Outer Space Act, which was adopted by the Austrian National Council on December 6, 2011, and entered into force on December 8, 2011, has its own definition where Section 2.2 of the Act defines “space object as: “...an object launched or intended to be launched into outer space, including its components;” This is more refined than the definition found in the Liability Convention.

- Aside from the inclusion of the term “space object,” Section 1.1 also defines the intended scope of the Code to cover all outer space activities. The annotations to this draft of the Code point out that some participants suggested that this Section 1.1 refer to the “…safety, security and sustainability of the peaceful uses of outer space activities”. However, other participants, considered the term “all” was inclusive to cover all outer space activities.

- There were no annotations discussing the change to the Section 1.4 of the Code nor the intent of the “without prejudice” language.

- Article 2(2) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties states: “The provisions of paragraph 1 regarding the use of terms in the present Convention are without prejudice to the use of those terms or to the meanings which may be given to them in the internal law of any State.”

- For instance, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals articulated a legal definition of customary law in United States v. Bellaizac-Hurtado, 700 F.3d 1245, 1252 (11th Cir. 2012). The definition of customary international law pronounced by the 11th Circuit in this case is unanimous throughout the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals.

- Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty contains two specific legal obligations and one legal right, but for the purposes of the Code one legal duty and one right is implicated. The first relevant legal obligation in Article IX creates a legal duty upon a State to consult with the international community, presumably through the United Nations and specifically the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), in the event a State believes its planned space activities, including those by non-government actors, will potentially cause harmful interference with the peaceful exploration or use of outer space by other State actors or their nationals. The legal right of Article IX that is implicated in the Code is the right for a State to request a consultation while another State is planning and before another State performs a space activity that could be potentially harmful or cause interference with other outer space activities. The Code contains a consultation mechanism in Section 7, which is similar to the existing consultation duty and right in Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty.

- Henkin, Pugh, Schachter and Smit, International Law, Cases and Materials, Third Edition, p. 429.

- Robert E. Dalton, Asst. Legal Adviser for Treaty Affairs, International Documents of a Non-Legally Binding Character, State Department, Memorandum, pp. 4–5, March 18, 1994, last visited October 20, 2015.

- Henkin, Pugh, Schachter and Smit, International Law, Cases and Materials, Third Edition, p. 429.

- Some proponents of the Code assert if a nation such as the United States subscribed to the Code the principles and “voluntary” measures within would become customary international law. That is to say acceptance of the Code and its principles would form the basis of legally-binding customary international law. This belief represents a fundamental misunderstanding of what it takes to create customary international law both in the eyes of the international legal community and the federal courts of the United States. It also raises the concern some proponents of the Code may be attempting to use the Code and TCBMs in the Group of Government Experts (GGE) to do the diplomatic equivalent of a draw running play to bypass the treaty authorization requirements by the Senate under Article II, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution. See generally, Michael J. Listner, “Customary international law: A troublesome question for the Code of Conduct,” The Space Review, April 28, 2014, for a discussion of the Code and customary international law.

- While a political agreement like the Code would be inferior to and not affect federal statutes, there is a question whether it could affect federal regulations, which is one concern Congress has about the Code. For example, some proponents of the Code may see the measure as a means of eventually regulating commercial space activities through an international bureaucracy that could grow out of a modified Code. More so, if the Code is intended to be controlling and a political promise is made to modify existing commercial space regulations through the Department of Transportation in order to comply with the desires of the subscribing states, would regulations pursuant to Title 51, Chapter 509 be required to be modified and could other subscribing states seek estoppel if the United States does not comply? On the other hand, there is a question whether the wording of Title 51, Chapter 509 indicates an intent by Congress to allow commercial space activities to be modified by non-binding, political agreements like the Code. See generally, Michael J. Listner, “Regulatory effect of the International Code of Conduct on commercial space,” The Space Review, March 17, 2014 for a discussion on whether the Code could implicate commercial space activities under the Article VIII jurisdiction of the United States.

- Henkin, Pugh, Schachter and Smit, International Law, Cases and Materials, Third Edition, p. 429.

- Prior to the July 2015 meeting at UN Headquarters in New York, some US proponents of the Code called for its signature by the US even though concerns within the agreement had yet to be worked out.

- Both the September 16, 2013, draft and the current draft of the Code expressly state the Code is a transparency and confidence-building measure. Section 1.3 states: “This Code establishes transparency and confidence-building measures, with the aim of enhancing mutual understanding and trust, helping both to prevent confrontation and foster national, regional and global security and stability, and is complementary to the international legal framework regulating outer space activities.” It is notable that the use of TCBMs to address outer space security is consistent with the National Space Policy, in that: “The United States will pursue bilateral and multilateral transparency and confidence-building measures to encourage responsible actions in, and the peaceful use of, space. The United States will consider proposals and concepts for arms control measures if they are equitable, effectively verifiable, and enhance the national security of the United States and its allies.”

- This goes back to the question of whether Section 1.4 implicitly intends for the Code to be controlling. If it is intended to be controlling, the Code could go beyond the “honor code” of TCBMs and create in essence a super-TCBM, which would be authoritative and subject a non-complying subscripting State to equitable enforcement, including estoppel.

- See generally, Andrey Makarov, Transparency and Confidence-Building Measures: Their Place and Role in Space Security, Security in Space: The Next Generation-Conference Report, 31, March–1 April 2008, United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR), 2008 for a discussion about TCBMs and their role in outer space security.

- At first blush there appears to be a conundrum in embracing TCBMs for data-sharing and distancing oneself from TCBMs like the Code. The conciliation rests in that TCBMs via USSTRATCOM are entered into bilaterally on a case-by-case basis with actors who have a direct interest in data provided by the agreements. This allows greater scrutiny of whom the TCBM is being entered into and what specific data will be shared. Bilateral TCBMs also allows a greater degree of control over sensitive information, which would protect national security and by extension US geopolitical interests. Conversely, multilateral TCBMs like the Code are difficult to negotiate because of the clash among the plethora of cultural and geopolitical interests. These competing interests give the United States less control over who is involved, what information is disseminated, who ultimately receives the information and, more importantly, what is done with the information.

- The Executive Branch has long claimed the authority to enter into political or “gentlemen’s agreements” on behalf of the United States without Congressional authorization. The assertion is entering into political commitments by the Executive Branch is not subject to the same constitutional constraints as the entering into legally binding international agreements. See generally, Robert E. Dalton, Asst. Legal Adviser for Treaty Affairs, International Documents of a Non-Legally Binding Character, State Department, Memorandum, March 18, 1994, last visited October 20, 2015.