Pluto and the gap beyondby Jeff Foust

|

| “Pluto and its system of satellites have really outsmarted us. It’s the best bad grade I’ve ever taken responsibility for,” said Stern. |

At the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences (DPS) conference earlier this month outside of Washington, DC, scientists offered their more detailed analysis to date of the images and other data New Horizons collected during the flyby. While still very preliminary, in part because less than a quarter of the data collected has been transmitted back to Earth, the analysis is reshaping our understanding of the distant world. But, at the same conference, scientists got a reminder that such missions of exploration into the outer solar system will, for fiscal reasons, be rare for the foreseeable future.

Pluto “outsmarted us”

It’s a bit trite, but planetary scientists have come to expect the unexpected in their first close encounter with a planet, moon, or other solar system body. But those working on the New Horizons mission seemed particularly surprised at what they’ve seen so far in the data the spacecraft has returned.

“I think it’s far to say we can tell that New Horizons gets a A for exploration,” mission principal investigator Alan Stern said at a press conference during the meeting, giving hypothetical grades for the mission.

“But I also think we get a couple of Fs. We get an F for predictive ability,” he added. “Pluto and its system of satellites have really outsmarted us. It’s the best bad grade I’ve ever taken responsibility for.”

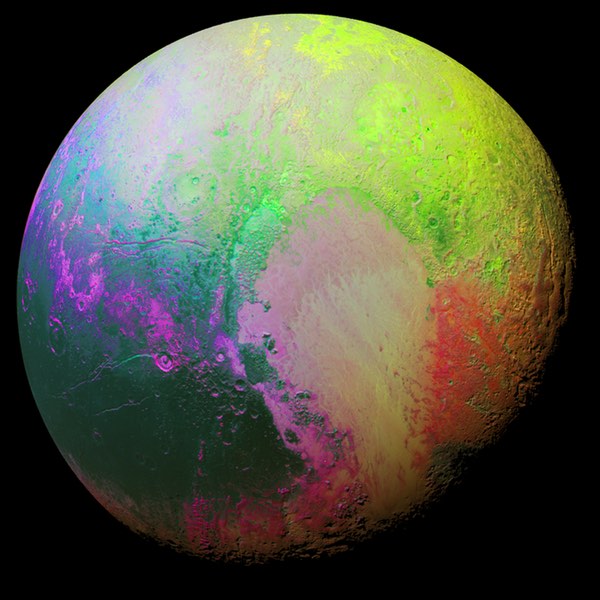

Pluto, it turns out, is far more diverse in its terrain, and far more active, than scientists previously expected. Among the discoveries discussed at the meeting were two mountains, provisionally named Wright Mons and Piccard Mons, with central depressions that scientists believe are cryovolcanoes: volcanoes that erupt molten ice rather than lava.

“Nothing like this has ever been seen of any kind in the outer solar system,” said Oliver White of NASA’s Ames Research Center at the press conference. If these are truly volcanic, he said, “it would be one of the most phenomenal discoveries of New Horizons and make Pluto an even more fascinating place.”

Another fascinating feature is Sputnik Planum, a basin that, based on the lack of craters, is geologically very young. “We have yet to find any craters there,” said Kelsi Singer of the Southwest Research Institute. While other regions are heavily cratered and likely about four billion years old, Sputnik Planum, she said, is no more than ten million years old.

The cryovolcanoes and the young age of Sputnik Planum suggest that Pluto is geologically active, surprising that, given its small size, most scientists thought it would have lost most of its internal heat by now. “The heat source may have died off quite a bit over the four and a half billion years of Pluto’s existence,” White said. However, he added that “quite volatile ices” on Pluto’s surface “wouldn’t require as much heat to be mobilized and to erupt onto the surface as rock would.”

Could it be something else other than volcanoes? “To tell you the truth, I’m having difficulty unseeing volcanoes,” White said. “While it’s crazy, it’s still the least crazy idea.”

Other discussions at the conference focused on Pluto’s tenuous atmosphere. Observations of the atmosphere showed it has a surface pressure of 10 microbars, which is consistent with previous stellar occultation observations of the atmosphere if those take into account the presence of a haze layer seen by New Horizons.

One of the surprises, said Leslie Young of the Southwest Research Institute, “was how little nitrogen there was at any particular altitude. This means that the atmosphere is much colder and more compact.” Models that explain this atmospheric profile, she said, have escape rates thousands of times smaller than previously expected. “This changes our thinking of the long-term evolution of Pluto and its atmosphere and its ices.”

| “To tell you the truth, I’m having difficulty unseeing volcanoes,” White said. “While it’s crazy, it’s still the least crazy idea.” |

Scientists stressed at the conference that their analysis remains very preliminary: New Horizons is still sending back data from the flyby, a task that won’t be completed until next November. The excitement, though, was palpable among scientists at the conference, who filled the Pluto sessions that dominated the first full day of the week-long meeting.

Except, though, when that excitement was accidentally squelched. At the beginning of the first day’s sessions, attendees were told that the results being presented were embargoed—not to be discussed outside of those in attendance, including on social media—until the midday press conference. That created a lot of grumbling among attendees, who had to sit on their hands all morning.

The embargo, it turned out, was a misunderstanding. “There was some kind of miscommunication,” said Curt Niebur, a program scientist working in the planetary sciences division of NASA Headquarters, after the press conference. “There was a little bit of organizational confusion.”

Some scientists, still struggling to analyze the data in hand so far, were cautious about making many conclusions. John Spencer of the Southwest Research Institute, in a talk about searches for small moons and dust surrounding Pluto, decided not to discuss any implications of the findings. “We have no idea what any of this means at this point,” he said.

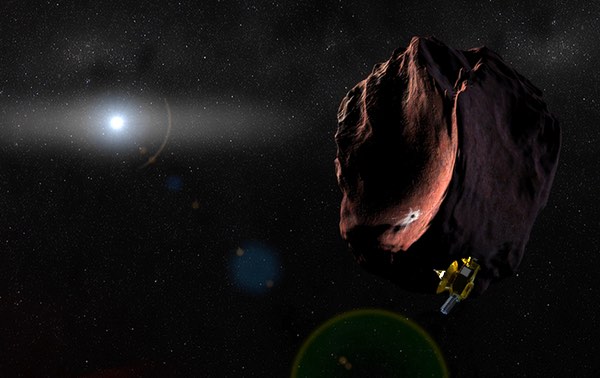

An illustration of New Horizons flying past the Kuiper Belt object 2014 MU69 on January 1, 2019. (credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI/Steve Gribben) |

The hazy future of outer solar system exploration

Even as New Horizons continues to transmit data from the Pluto flyby back to Earth, the mission is looking ahead for another encounter. The spacecraft completed a series of thruster firings earlier this month that put the spacecraft on course to fly fast a Kuiper Belt object designated 2014 MU69 on New Year’s Day 2019.

Besides providing a closeup look at a small Kuiper Belt object for the first time, 2014 MU69 could give planetary scientists insights into the formation of the solar system. “If an extended mission is approved and we can actually fly to this object and explore it, it will be the first of this class of object that we’ve ever seen,” said Alex Parker of the Southwest Research Institute. It’s possible, he said, that “this object that we’re flying by is actually a surviving extant relic” of the planetesimals from which the larger objects of the solar system formed.

That excitement about that future flyby, though, is balanced by concern about the long-term future of outer solar system exploration. With the Cassini mission orbiting Saturn ending in 2017, and the Juno mission to Jupiter currently scheduled to end in 2018, less than two years after entering orbit, the New Horizons flyby in 2019 could be the last major spacecraft event in the outer solar system for up to a decade.

| “We need to keep an eye on this gap,” Hansen said. “Basically, there’s a long stretch, about a decade, without an outer solar system mission in flight.” |

“We have a challenge, which is how to keep our community vibrant in the absence of actual missions in flight,” said Candy Hansen of the Planetary Science Institute. She is chair of the Outer Planets Assessment Group (OPAG), a NASA-chartered committee looking at issues regarding planetary science in the outer solar system, which held a town hall meeting at the DPS conference.

There are future missions on the books, including NASA’s Europa Clipper mission and a similar European mission, the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE). Neither mission, though, will arrive at Jupiter until the late 2020s.

“We need to keep an eye on this gap,” Hansen said. “Basically, there’s a long stretch, about a decade, without an outer solar system mission in flight.”

Hansen said she was hopeful about a provision in the House version of the appropriations bill funding NASA for fiscal year 2016 that directs the agency to establish an “Ocean Worlds Exploration Program.” The purpose of the program would be to support missions to Europa, as well as Saturn’s moons Enceladus and Titan. Its “primary goal is to discover extant life on another world using a mix of Discovery, New Frontiers and flagship class missions consistent with the recommendations of current and future Planetary Decadal surveys,” according to the report accompanying the bill.

That provision is the handiwork of Rep. John Culberson (R-TX), chairman of the appropriations committee that funds NASA and an ardent supporter of a Europa mission. That bill also provides $140 million for a Europa mission, several times the administration’s request.

“They are words that are like a gift to our community,” Hansen said of the Ocean Worlds language. “When we went through this at the [August] OPAG meeting, we all decided this was a great idea.”

Whether that language makes into the final omnibus spending bill, expected to be completed before the current stopgap funding bill for the government expires December 11, remains to be seen. There is a gap of more than $200 million between the $1.56 billion the House allocated for NASA’s planetary science program and the $1.321 billion the Senate provided in its version.

“I’m not personally too worried” about the lower Senate funding level, Casey Dreier, director of advocacy for The Planetary Society, said during a policy panel at the DPS conference. In recent years, the House request for planetary science has won out in negotiations with the Senate. Moreover, a two-year budget deal reached in October that lifts spending caps may give NASA some additional spending flexibility. “Historically, I’m optimistic about where this is going to go.”

| “Savor those two launches of OSIRIS-REx and InSight, because they will be the last launches of planetary missions that we’ll see for three years,” Dreier said. |

However, he reminded attendees that NASA’s planetary sciences program in general is still recovering from cuts first made by the administration a few years ago that has stretched out timelines for new missions, affecting not just outer solar system missions but planetary exploration in general. “Planetary science is in a process of rebuilding,” he said.

As an example of that rebuilding, Dreier noted that the overall planetary program is facing a gap of its own: after the launch of the Mars InSight lander and OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample return missions in 2016, the next NASA planetary mission won’t launch until 2020. That’s the longest gap in planetary missions, he said, in at least 20 years.

“Savor those two launches of OSIRIS-REx and InSight, because they will be the last launches of planetary missions that we’ll see for three years,” he said.