A little something for almost everyoneby Jeff Foust

|

| Instead of a lineup of winners and losers, most of the agency’s programs—with a few exceptions—got what they wanted and then some. |

When House and Senate negotiators released the final version of an omnibus spending bill—so named since it combined a dozen separate bills into a single piece of legislation—in the early morning hours last Wednesday, the budget battle turned out not to be a zero-sum game. Thanks to a broader budget agreement approved in October that lifted spending caps on defense and other discretionary programs, like NASA, appropriators were able to spread the wealth. Instead of a lineup of winners and losers, most of the agency’s programs—with a few exceptions—got what they wanted and then some.

NASA overall received $19.285 billion, $755 million above its original request. That largess came in the final budget negotiations, after the budget agreement. A House bill passed in June funded NASA as its original request (albeit with shifts of funding within agency programs), while a bill Senate appropriators approved in June offered only $18.3 billion for NASA.

A quick review of the budget showed some clear winners. One of the biggest was SLS. NASA had requested a little more than $1.35 billion for the heavy-lift launch vehicle in its 2016 budget request, an amount criticized by the vehicle’s Congressional proponents as far too small. SLS instead received $2 billion in the final bill, nearly 50 percent above the request and more than even the increase earlier provided in the House and Senate bills.

Planetary science also got a healthy increase. NASA’s original request proposed $1.36 billion for the program, including $30 million for a mission to Europa. The omnibus instead gives the program $1.63 billion, with $175 million of that earmarked for a Europa mission.

Other programs won by not losing. NASA’s Earth sciences program received almost exactly what it requested: $1.921 billion versus the agency’s request of nearly $1.95 billion. That doesn’t sound like much of a victory in and of itself, but that calculus changes when recalling that the House bill made a cut of more than $250 million in that program.

NASA’s commercial crew program got, in the omnibus, exactly what it requested: $1.2438 billion, after House and Senate bills offered several hundred million dollars less. In an accounting shift, Congress moved the program from NASA’s exploration account, which funds SLS and Orion, to space operations, which funds operations of the International Space Station.

Not every program got what its requested. A couple of agency accounts that handle internal infrastructure and operations, construction and safety, security and mission assurance, each received about $75 million less that requested. Space technology received $686.5 million, nearly $40 million less than the administration requested, but more than what the House and Senate bills offered.

The report accompanying the bill, with additional details about spending levels and other requirements, offered a more nuanced view of what appears to be a big budget win for NASA. While the agency gets significantly more money, some of that funding comes with new strings attached.

The SLS funding, for example, directs that NASA spend “no less than” $85 million on a new upper stage for the vehicle, called the Exploration Upper Stage (EUS) by NASA. That stage was intended for use on missions after the first SLS launch, which will use a modified Delta IV upper stage called the Interim Cryogenic Upper Stage.

NASA officials earlier this year suggested, though, that it might have to use that interim stage on additional missions because of limited funding for the EUS. The bill, besides providing the funding for the EUS, prohibits NASA from spending any money to human-rate the interim stage. That would have been required if NASA flew it on the second SLS mission, the first that will carry a crew.

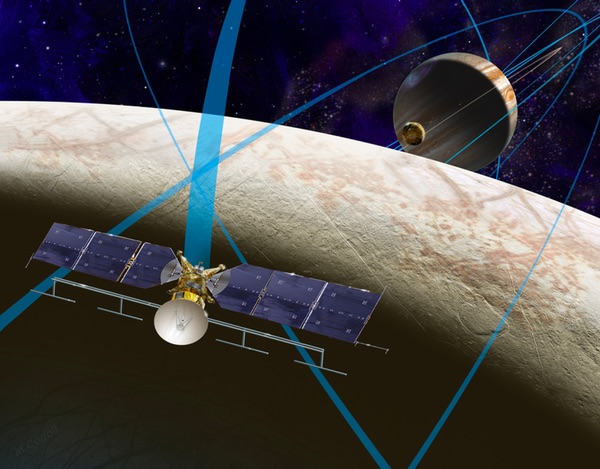

The planetary science account got a generous increase, but NASA also got more direction on its plans to send a mission to Jupiter’s moon Europa. The $175 million included for the mission in the bill would go towards a mission that “shall include an orbiter with a lander that will include competitively selected instruments and that funds shall be used to finalize the mission design concept with a target launch date of 2022.”

| To keep commercial crew’s 2017 schedule, the report suggests that NASA “derive resources for milestone payments from funds set aside for Russia by NASA for ISS crew launches scheduled to occur after U.S. providers will be operational in 2017.” |

NASA is working on a Europa mission based on the “Europa Clipper” concept that would place a spacecraft into orbit around Jupiter, rather than Europa itself, and make dozens of close flybys of the icy moon. It’s not clear if the language would require the spacecraft to be a Europa orbiter, versus simply a Jupiter orbiter. In any case, the Clipper design did not originally include a lander, and while a team at JPL has been looking at lander concepts, it would likely add significantly to the roughly $2-billion cost of the original mission.

Commercial crew got its full funding after NASA warned that it would have to extend contracts with Russia for Soyuz flights to and from the ISS, and took steps in August to formally extend its contract with Roscosmos to cover missions in 2018. Congress, in providing NASA’s exact request for funding, also pressed NASA to have those vehicles ready for flights by the end of 2017.

“The funds provided in this Act enable NASA to follow the fastest path to independence from Russia by providing for continuing development of a domestic crew launching capability,” the report states. To keep that 2017 schedule, the report suggests that NASA “derive resources for milestone payments from funds set aside for Russia by NASA for ISS crew launches scheduled to occur after U.S. providers will be operational in 2017.”

The space technology program, despite the cut from its request, also faces some additional direction. The bill directs NASA to spend $133 million of the program’s budget—about 20 percent of its overall final budget—on a satellite servicing project called RESTORE-L that seeks to refuel the aging Landsat 7 satellite. NASA has tied some of the technologies proposed for RESTORE-L for use on the Asteroid Redirect Mission, but the report instructs NASA not to spend any of the $133 million on satellite servicing technologies needed solely for ARM.

The bill’s report also includes some interesting language about the development of habitats intended for future human missions in cislunar space and, later, Mars. The report directs NASA to spend at least $55 million from its exploration account to work on a “habitation augmentation module” to be used with SLS and Orion. “NASA shall develop a prototype deep space habitation module within the advanced exploration systems program no later than 2018,” the report states.

NASA has already stated it was planning to develop a hab module of some kind in the coming years, but the schedule laid out in the report appears more ambitious than NASA’s plans. The agency awarded contracts earlier this year to four companies—Bigelow Aerospace, Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Orbital ATK—to perform studies on each companies’ own hab concepts that, after their completion in 2016, would feed into future, unspecified NASA work.

It wasn’t clear how the funding and direction provided to NASA’s hab work would affect that work. Sam Scimemi, director of International Space Station at NASA Headquarters, said in at a Space Transportation Association Wednesday, just hours after the release of the bill, that the agency was still studying the direction provided in the report.

Some in industry, though, welcomed the hab module language in the bill. “We’re thrilled that Congress took the lead,” said Mike Gold, director of DC operations and business growth for Bigelow Aerospace, in an interview last week. He noted that the language also requires NASA to provide a report to Congress on its habitat plans 180 days after the bill became law, including “an analysis to determine the appropriate management structure for this program.”

NASA has, in general, taken a low-key approach to this latest budget, not offering official press releases or other statements about the funding it won for 2016. Other organizations, though, praised the bill in a series of statements.

The Coalition for Deep Space Exploration, for example, applauded the additional funding Congress provided for SLS and Orion. “The robust funding levels achieved in the omnibus will support the continuing development of America’s new space exploration systems, leading to the launch of Exploration Mission-1 in 2018,” said the organization’s executive director, Mary Lynne Dittmar, in a statement.

| It’s a big win, but is it a lasting one? The additional funding papered over differences of opinion about NASA’s priorities, including science and exploration, by adding enough money to give most constituencies what they wanted in terms of funding without having to take money from other programs. |

The Commercial Spaceflight Federation noted the full funding for NASA’s commercial crew program in the final bill. “The funding levels in this legislation reaffirms strong bipartisan, bicameral support for public-private partnerships that harness commercial space capabilities to help build a sustainable American expansion into the solar system from the edge of space to low-Earth orbit and beyond,” said CSF president Eric Stallmer in a statement.

The Planetary Society, of course, weighed in on the increased funding for planetary sciences. “We reached—and exceeded—The Planetary Society’s goal of $1.5 billion per year for NASA's planetary exploration program,” Bill Nye, the organization’s CEO, said in a statement. “This is a big win for NASA, planetary science and all of Earth’s citizens who understand and advocate the need to explore other worlds.”

It’s a big win, but is it a lasting one? The additional funding papered over differences of opinion about NASA’s priorities, including science and exploration, by adding enough money to give most constituencies what they wanted in terms of funding without having to take money from other programs. The final bill could, in fact, exacerbate those differences, particularly in the additional direction it gives NASA in areas like a Europa mission of development of cislunar habitats.

More money again next year could help avoid another round of debates, but it’s unlikely that, even with the two-year budget deal reached in October, NASA could expect another increase of similar scale for its fiscal year 2017 budget. There’s a widespread impression on Capitol Hill that much of the increase in discretionary spending that two-year deal allowed was spent in 2016. That means limited increases, or flat budgets, for 2017.

Moreover, 2016 is a presidential election year, and the final year of the current administration. Any significant changes to NASA, including reprioritization of agency efforts, may have to wait until after the next president takes office in January 2017.