Implementing a space weather strategyby Jeff Foust

|

| “If this event had occurred just a few days earlier, when the Earth was in the line of fire,” Baker said of a July 2012 storm, “I contend that we would still be picking up the pieces from this storm.” |

Fortunately, that was the extent of the impact that the Carrington event had on Victorian-era civilization, one without power grids, radio communications, and satellites. Today, a storm of similar intensity would be far more devastating. “If an event of that size were to occur today, the effects would be, by most estimates, devastating,” said Daniel Baker, director of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado, during a session on space weather threats at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in Washington last month.

How devastating? Such a storm, he said, could destroy hundreds of house-sized transformers on the backbone of the power grid. “The cost of replacing them could run into the trillions of dollars and take years to affect,” he said.

A powerful solar storm, he said, could interfere with GPS signals, which play a fundamental role in navigation and many other applications. “The fact that these powerful storms can affect the ionosphere and thereby affect the use of GPS and other technological systems is a very important issue,” he said.

Those dangers have, by and large, been understood for some time. But how big is the risk of another Carrington event? And, what can government agencies, and others, do to mitigate the potential impacts of such a storm?

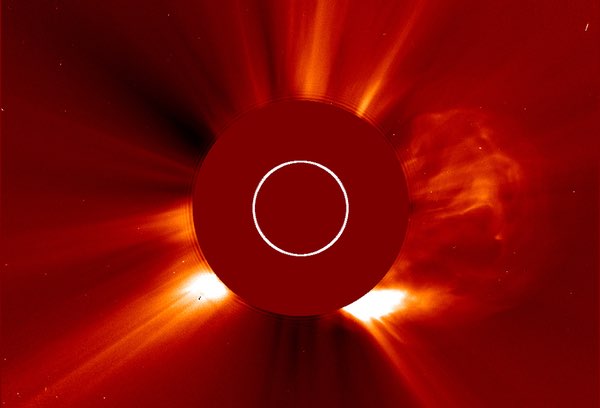

The space weather field got a wakeup call in 2012, when a powerful solar storm that Baker said was comparable to the one that created the Carrington event missed the Earth by just a few days. “If this event had occurred just a few days earlier, when the Earth was in the line of fire,” he said, “I contend that we would still be picking up the pieces from this storm.”

Was that, though, just a fluke event? At the AAAS panel, Pete Riley, senior research scientist at Predictive Science Inc., offered a probabilistic forecast for the likelihood of another Carrington-like event, based on that storm’s estimated strength and measurements of the actual strength of solar storms over the last few decades. “If you the time between events, you can calculate the probability of the next event occurring within some unit of time,” he explained.

His estimate of the probability of another Carrington event is surprisingly high: about a 10 percent chance of such an event occurring over the next decade. “Ten percent is very, very high,” said William Murtaugh, assistant director for space weather at the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), at the AAAS panel. “A one-percent probability over the course of the next one hundred years of a storm with an impact of that magnitude is considered very, very high and will motivate action.”

That ten-percent estimate, though, is couched with many uncertainties. For example, the actual strength of the storm that created the Carrington event is not known; if the storm was, in fact, twice as strong, the probability drops from around ten percent to around one percent. Different modeling approaches to the historical record can also produce different probabilities.

| “This issue of space weather is a lot more than” a science and technology issue, Murtaugh said. “This issue is a national security concern, a homeland security concern.” |

Riley also noted that while solar storms had been slightly increasing in intensity over the last few 11-year solar cycles, there was not a corresponding increase in the latest peak in activity earlier this decade. “There are some people who are speculating that we are entering into a grand solar minimum,” he said, that could last for decades. “What we’re predicting in the future is based on previous data that’s not as relevant going forward.”

Whether that risk of another Carrington event is ten percent or one percent over the next decade, the US government is starting to take steps to prepare for one. Last fall, the administration released the first National Space Weather Strategy and a corresponding National Space Weather Action Plan that describes steps various federal agencies should take to better understand the risks posed by solar storms and be prepared to take action.

Having a national strategy at the level of the White House, Murtaugh said, is important because the issue cuts across various agencies, and not just science and technology. “This issue of space weather is a lot more than that. This issue is a national security concern, a homeland security concern,” he said.

The strategy document outlines six major goals to deal with the threat posed by solar storms, from improved data on space weather events and modeling of their effects on critical infrastructure to improved “response and resiliency capabilities” in the event of a storm. The action plan builds upon that strategy by describing specific tasks to achieve those goals and assigning them to various agencies.

The administration is starting to back up that plan with funding. Murtaugh noted that the fiscal year (FY) 2017 budget request includes $10 million for NASA’s heliophysics program to do research to help set benchmarks for space weather events, one of the goals of the overall strategy. The U.S. Geological Survey’s geomagnetism program will get its budget doubled—albeit to only a little more than $3 million—to better understand the conductivity of the Earth, a key factor affecting the severity of solar storm impacts.

Much more is needed, though, he acknowledged, including a dedicated satellite at the Earth-Sun L1 point to provide early warnings of solar storms, a spacecraft he estimates will cost on the order of half a billion dollars. There are also activities planned at agencies like NOAA and the Department of Homeland Security, but are not explicitly called out in the budget proposal.

“We were rushing to try and get this strategy done in time to influence the FY17 budget,” which was already in an advanced stage of planning when the strategy and action plan came out. “We had some success, but not as much as I would have liked. So it will obviously be in the next budget.”

| “Fortunately in space weather there’s no real politics,” Murtaugh said. |

That next budget proposal, though, will come from a new administration, which might also have different priorities. Murtaugh said the change in administrations will likely result in a turnover of about 80 percent of the staff at OSTP, but that the space weather task force that helped create the space weather strategy and action plan will be incorporated into the National Science and Technology Council to help maintain continuity during the transition.

Space weather, he added, has considerable support in Congress, including a proposal for a space weather research and forecasting act that could soon be introduced in the Senate. “Fortunately in space weather there’s no real politics,” Murtaugh said. “Both sides of House, both sides of the Senate, Republicans and Democrats, are both keen to work together to do something about this issue.”