Giant steps are what you take, walking on the Moonby Dwayne Day

|

| Had the Soviets ever gotten that far, had they ever sent Leonov to the Moon, he would have died rather than eventually become a genial geriatric cosmonaut, ambassador of the Soviet space program, and living legend. |

In some ways, my trip was a pilgrimage, an homage. The special exhibit, “Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age,” closed yesterday (see “Review: Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age”, The Space Review, December 7, 2015). It was a fascinating display of Soviet-era space equipment, the largest single display outside of Russia. Starting today, if you want to see a good collection of Russian space equipment without going to Moscow, your best bet is probably to go to the United States, either to the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, or the Kansas Cosmosphere. The Smithsonian has a flown Soyuz capsule, a mockup, an enigmatic TKS spacecraft, a space suit, and even a Venera Venus orbiter as well as numerous smaller items. The Cosmosphere has a number of relatively minor artifacts, but does a great job putting them in the context of the space race with the Americans.

The London exhibit was many years in the making and delayed by bureaucracy and threatened by politics, but it eventually happened. According to one of the museum’s curators, who gave a public talk at the museum in late February, many of the artifacts on display were not from public Russian museums but from museums or collections within Russian aerospace companies or technical institutes. Those organizations tend to view their artifacts from a more “commercial perspective” than is common in the West, a polite way of saying that they wanted to be compensated for loaning them abroad and were not doing so out of good will or the interests of cultural outreach.

The curator explained that the large objects in the exhibit—specifically the crewed spacecraft—presented difficult logistics challenges. One problem was that Valentina Tereshkova’s spacecraft’s heat shield includes asbestos and part of it had been crushed, meaning that the asbestos could become airborne. The London museum curators had to travel to Russia to encapsulate the capsule for transport, donning protective clothing and respirators for the job, which mystified their Russian counterparts, who do not consider asbestos to be a hazardous material. Simply getting the large artifacts into the museum was not easy, and they practiced moving Tereshkova’s capsule through the museum by using a large inflatable beach ball.

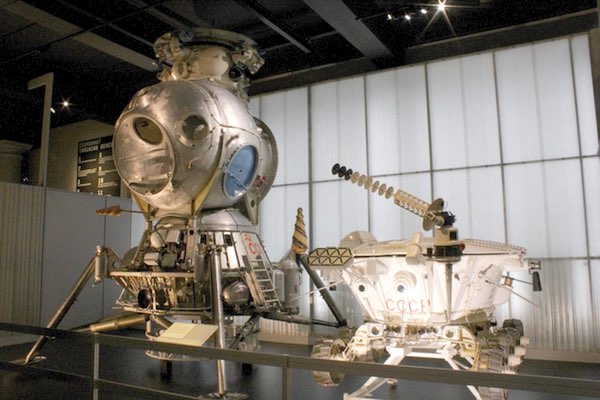

The Lunniy Korabl is one of only five engineering mockups built, each one different than the others. LK-3 is the most complete one of those five. The LK looks top-heavy and more awkward than its distant American relative, the larger Grumman Lunar Module. The landing sequence for the LK was risky, involving a “crasher stage” that would slow the craft down just above the surface before being jettisoned by the lone cosmonaut inside. At that point the pilot had only about sixty seconds to land before having to abort—using the same engine for both descent and ascent. Apollo 11 Lunar Module Pilot Buzz Aldrin noted that if that engine failed “they were splattered.” There was no backup engine. The margin for error was nonexistent. Alexei Leonov, truly a superman among cosmonauts, probably would still be on the surface today if they had tried—and not in one piece.

| Apollo 11 Lunar Module Pilot Buzz Aldrin noted that if that engine failed “they were splattered.” The margin for error was nonexistent. |

For students of the Cold War space race, the LK is somewhat of a mystic object. During the 1960s the Soviet leadership never confirmed that they were racing the Americans to the Moon. It was in their nature to be secretive about their space activities, but this secrecy might have been encouraged by the fact that they knew—when their space leaders experienced infrequent moments of clarity—that they were doing badly. Like an Olympic runner who has gotten out of shape, they may not have wanted to admit that they were even trying.

Once the Americans landed on the Moon, it became common for the Soviet leadership to deny that they had been in a race at all. The Americans were foolish, they claimed, and wasted a lot of money racing themselves. In contrast, the wise Soviets instead used robotic spacecraft to return lunar samples and rove the surface. Despite the fact that there were also contradictory statements from Soviet officials and even cosmonauts, this narrative gained traction in the Western media, and even space fan Walter Cronkite embraced it. Any American evidence to the contrary, in the form of reconnaissance photos of the massive Moon rocket launch site at the Baikonur Cosmodrome, was highly classified.

In August 1989 the Soviet newspaper Izvestia published an article with substantial details about the N-1 lunar rocket program. Rough translations quickly appeared in the West. But a bigger revelation happened in November 1989 when a group of engineering professors from the Massachussetts Institute of Technology and California Institute of Technology visited the Moscow Aviation Institute and saw a strange-looking craft.

An MIT engineer, Laurence R. Young, recounted the visit in an interview with John Noble Wilford, of the New York Times. “It was one of the most dramatic moments that I can remember,” Young said. “I said, ‘What is that?’ And they said, ‘Oh, that is the lunar lander.’ All the pieces were there, and they explained to us which part was connected to which other.” It was not a mockup, but flight hardware. MIT acting dean of engineering Jack L. Kerrebrock returned the next day and took photographs. The photos were soon published in various media and suddenly Westerners—and the Russian public as well—saw what the Soviet Union had been trying to do, and had kept hidden for decades.

| Godspeed, Lunniy Korabl, it was great to finally meet you. |

The descriptions of the Soviet lunar effort that emerged in the late 1980s and early 1990s were garbled and not totally accurate. For example, the initial account that the visiting MIT group was told was that the Soviet lunar mission would have involved two rocket launches and a rendezvous in orbit. This was untrue and it took several years for a more accurate account to emerge. The most authoritative Western account came in 2000 with Asif Siddiqi’s monumental book Challenge to Apollo. Although much new material has emerged since then, Siddiqi’s book remains the best English-language source on that subject. In a sign of how much had changed since the Cold War space race, Siddiqi’s book was published by NASA, a sign of respect to the agency’s former rivals.

Relations between Russia and the United States have soured in recent years. But politics is often cyclical, and the current chill will eventually thaw… someday. Perhaps when that happens, the lunar ship will again venture out on another voyage, not into space, but to another country, where space enthusiasts of a certain age can look at it in wonder, and dismay. Considering the rickety nature of the craft, it is better suited to horizontal travel than vertical. Godspeed, Lunniy Korabl, it was great to finally meet you.