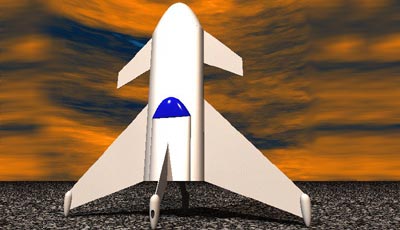

The promise of amateur suborbital spaceflightHomebuilt spacecraft could soon take to the skiesby Andrew Case

|

| An obvious question to ask is whether we can expect, as in the case of aviation last century, the participation of private individuals and clubs in this second golden age of spaceflight. |

Before the announcement of X Prize, a group of spaceflight enthusiasts started a serious paper study of a homebuilt suborbital vehicle called SpaceCub. Following a suggestion by Geoff Landis, they worked out many of the issues facing small suborbital vehicles designed for construction using techniques within reach of private individuals. David Burkhead, who did much of the serious design work, maintains a website dedicated to this project. The project is not currently active, though there has been a minor resurgence of interest in it due to the publicity surrounding the X Prize.

The technical challenges

Since there are groups of individuals attempting to build private spacecraft, the obvious question to ask is “Do they have a realistic prospect of success?” I believe the answer to this question is a qualified “yes.” The basic requirements for an X Prize-class mission (three people to 100 kilometers and back safely) are relatively modest. The total change in velocity required is roughly 2 kilometers per second. Using readily available propellants, such as liquid oxygen and kerosene or isopropyl alcohol, the required propellant load comes to about 65% of the vehicle liftoff weight.

The necessary technologies for a suborbital spacecraft are all within the realm of projects amateurs have already done, with the exception of the rocket engines and flight control systems. Amateurs have constructed rocket engines of sufficient thrust in the past, but the reliability of amateur-built rocket engines is nowhere near the level needed for use on a crewed vehicle. One possible way around this is to purchase engines from one of the small rocketry startups, some of which have indicated a willingness to sell engines to the general public (although there are issues with arms control regulations that make it difficult or impossible for US companies to sell rocket engines to non-US citizens). Apart from the engines, flight control systems are the other great challenge. It is probably possible to adapt existing flight control systems from aircraft for use in rockets, but this is likely to be quite expensive. There are a number of possible solutions to this problem, but at this time there is no obvious simple answer such as the purchase of an existing system. Within a few years the demand may be large enough for companies to start producing suborbital spaceflight versions of aviation avionics, but currently the only route is roll-your-own. Armadillo Aerospace has successfully created a control system for their vehicle based on commercially-available hardware, and the Experimental Rocket Propulsion Society (ERPS) has also constructed a flight control system from commercial components that has been tested on a helicopter-type platform. The ERPS flight control system is slated to fly on a rocket vehicle later this year.

| The necessary technologies for a suborbital spacecraft are all within the realm of projects amateurs have already done, with the exception of the rocket engines and flight control systems. |

The forces experienced by an X Prize class vehicle are well within the range of those felt by other amateur-built vehicles, such as acrobatic aircraft or oceangoing yachts. For an appropriately designed spacecraft, the required construction techniques will be similar to those already in use by aircraft homebuilders. Looking at aircraft as a model, it’s clear that the similarities are significant. Aircraft homebuilders do not build their own engines: they purchase them, as they do with the avionics. The early aircraft homebuilders used engines from other vehicles (often motorbikes) for propulsion. There is no analogous technology that can be pressed into service for the spacecraft homebuilder, so we are going to have to either build or buy. Fortunately pressure-fed rocket engines are relatively simple, so building your own isn’t out of the question.

One of the other areas where homebuilders construct substantial vehicle is oceangoing yachts. In the case of a homebuilt yacht built for blue-water cruising, the builder typically buys the engine(s) and the navigational instruments. Once again, propulsion and guidance and control systems are purchased. This is certainly a reasonable model for a well-developed homebuilt spacecraft community. Between the point where we are today and the point where starry-eyed dreamers can pick up a catalog full of rocket engines and astronautical instruments there are a number of important things that need to happen.