A vision from the pastA review of the Atlantic Council’s ideas for a not-so-new National Security Space Strategyby Christopher Stone

|

| The authors of the white paper believe there is a “slipping back toward the ‘dominance and control’ motif of the Bush Administration’s space policy.” |

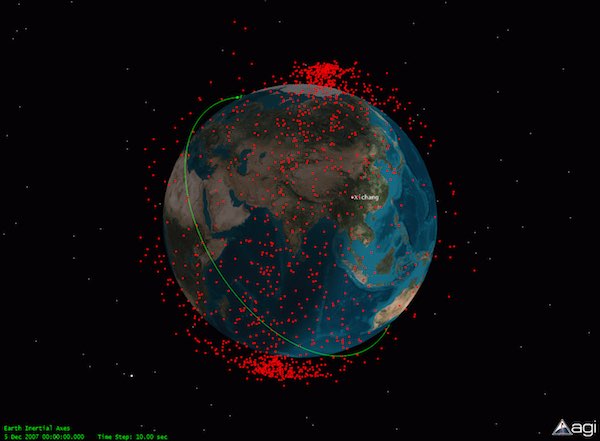

The authors begin by giving some history of the NSSS, arguing that the administration redirected the United States toward a more cooperative, civilian, and commercial oriented program overall, including a more traditional space security strategy of “strategic restraint” rather than the Bush Administration’s “hegemonic” space policies and strategies.2 They describe “strategic restraint” as where “under Obama, the United States would once again restrain itself from introducing offensive capabilities in hopes of moderating the behavior of both friends and potential foes.”3 Following this release of the NSP and NSSS, the authors assert a national and international “consensus” toward this approach regarding mutual restraint and vulnerability and the NSSS’ space deterrence framework developed between 2011 and 2013.4 However, after the Chinese geostationary orbit (GEO) anti-satellite (ASAT) test in May 2013, the consensus began “to unravel”.5

They believe that, despite the concern generated by the Chinese GEO test among space professionals in the United States and allied capitals, the United States “overcorrected”6 following the 2014 Strategic Portfolio Review-Space. This review was conducted within the national security space arena of the Department of Defense and Intelligence Community and, despite the events that triggered this review, the authors claim “inertia [of these concerns in Congress, the Administration and within space professional circles] should not drive U.S. space security policy.”7 To get America back on course, they believe a “new” NSSS should be an “assessment” of “risks and threats” and a “rebalancing of means used to address U.S. goals in space… through the next ten to twenty years.”8

They added that “above all [the United States] must not be driven into a space-arms competition that includes indiscriminate weapons—weapons that could destroy the space environment for the very commercial and civil uses that are so benefiting the country, and the world at large.”9 This concern they share is based on what they claim is a “more muscular national security space strategy” they believe is currently being pursued by the United States in both policy and budgetary arenas. They also believe there is a “slipping back toward the ‘dominance and control’ motif of the Bush Administration’s space policy.”10

Despite the push for an assessment of threats and risks, the authors state that “the United States does not face an imminent threat to national security space missions,” calling recent tests by Russia and China “just that—demonstrations and perhaps signaling.” They continue: “There is no Russian or Chinese ASAT fleet deployed that could defeat US space operations in a conflict, both nations are still behind the United Sates in the integration of space assets into military operations, as well as in orbit technology development and no other potential adversary is even close to achieving equivalent space power.”11 So what then is the threat to American space power? The authors believe this threat to be “debris and overcrowding in usable orbits.”12

The authors recommend remedying the Defense Department’s overcorrection of and improving the current NSSS with the following actions:

- Provide a chance to stop activities and actions that would degrade the space environment, and consequently impair the beneficial uses of space by all, through development of norms and roles that establish the lines between acceptable and unacceptable behavior.

- Create space to establish better dialogue, with Russia and China in particular, about US “bright lines” in space, and mutual assurance measures that would reduce risks of misconception and conflict, as well as establish “breakers” to dangerous conflict escalation.

- Avoid the opportunity costs an arms race in space would engender.

- Buy time (and resources, per avoiding opportunity costs) for private industry, which is in the middle of a renaissance, to develop low-cost solutions to space resiliency that can help the U.S. national security space community get out of the situation of having space be a potential single point failure in a conflict, as well as complicate an attacker’s abilities to degrade or defeat the advantages provided to the US military by space assets.

- Allow the US Air Force and Intelligence Community to figure out protection strategies and technologies for those space assets that will be more difficult to commercialize, otherwise disaggregate, and offload missions from.

- Allow the USgovernment and industry the time and budgetary leeway to develop next generations technologies, which might keep a leading edge in space, both for commercial benefits and military hedging of advantage.13

These steps offered by the Atlantic Council’s report are proffered as part of a strategy of “proactive prevention” to avoid war in space and prevent the space environment from being rendered unusable.

Analysis of “Proactive Prevention”

The subject matter discussed in the Atlantic Council paper is a complex area of national strategy and has far reaching impacts to all the instruments of national power and not just “national security space systems,” which the paper seems focuses on.

A point-by-point analysis of the Atlantic Council’s recommendations follows:

| The Atlantic Council’s “Diplomacy First” initiative is a rephrasing of the present policy promoted by the Obama Administration and the Defense Department. This policy approach hasn’t deterred China or Russia from pursuing kinetic-energy ASAT testing. |

Analysis: This recommendation is not new. It’s a re-wording of what is referred to in the present NSSS and the Eisenhower Center study as “deterrence through norms,” which served as the foundation for the NSSS. It is essentially saying, more colloquially and concisely, what the NSSS states when it declares its goal is to dissuade and deter the “development, testing, and employment of counter-space systems and prevent and deter aggression against space systems and supporting infrastructure, which supports U.S. national security.”14 A read of the present NSSS and the various speeches, hearings and testimonies of then-Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy Ambassador Gregory Schulte demonstrates “the first layer of deterrence is the establishment of norms of responsible behavior… This helps separate responsible space-faring countries from those who act otherwise.”15 With respect to the concern about preventing degradation of the space environment, this “deterrence through norms” mentioned in the NSSS would “help ensure the long-term sustainability of the space environment.”16

Analysis: This recommendation is not new. The NSSS in its current form promotes a “top down diplomatic initiative”17 as well as the development of numerous “diplomatic engagements” that will “enhance our ability to cooperate with our allies and partners” as well as “seek common ground among all space-faring nations”18 to prevent “mishaps, misperceptions, and mistrust.”19 The Atlantic Council’s “Diplomacy First” initiative is a rephrasing of the present NSSS and NSP promoted by the Obama Administration and the Defense Department. This policy approach hasn’t deterred China or Russia from pursuing kinetic-energy (KE) ASAT testing. These two nations represent the two most aggressive in terms of pursuing active counter-space weapons systems and are also the most notorious for the creation of space debris through lack of mitigation measures and a lack of passivation of spent stages and spacecraft in key orbits. Interestingly, the report leaves out this fact when discussing “rebalancing” of US means to the threat posed by other nations to our critical space infrastructure and those of our allies.

Analysis: Again, this is not new, as it was one of the main points of the NSSS, and Ambassador Schulte’s push for it and the NSP in 2011. When both came out, arms control agreements and later codes of conduct were pursued because proponents like Hitchens argued the Chinese and Russians (among others) had responded to the Bush Administration’s “unilateral” space policy of 2006 (despite the fact ASAT efforts in both nations had been underway for years prior to the release of that document.)20

None were successfully achieved because, in the perspective of then-Under Secretary of State for Arms Control Ellen Tauscher, “we will never do a legally binding agreement because I can’t do one. I can’t get anything ratified.”21 Alternatively, the arms control community pursued code of conducts relating to “behavior” of state actors in space. One of the primary positions of such a non-legally binding Code of Conduct included “the importance of preventing an arms race in outer space.” This non-legally binding agreement of the Code of Conduct, which began with the EU and then embraced by then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton22 as the International Code of Conduct, never reached critical mass to get an international buy-in, despite the authors’ assertion that there was “consensus”23 either multilaterally or within the confines of the United Nations fora.

Furthermore, their collective statement that “There is no Russian or Chinese ASAT fleet deployed that could defeat US space operations in a conflict...” highlights a lack of understanding of the strategic culture of both nations, and specifically that of China. The goal or intent of an adversary developing an ASAT capability may not be to “defeat” all US military space operations, but rather create a shock to the system that sufficiently slows down terrestrial operations enough to enable the adversary to achieve its objectives. Thus their argument makes very little sense from a historical review of counter-space activities.

This makes the push for arms control and the prevention of an arms race in space nothing new to deal with this threat. Moreover, if the NSSS as written was going to do what it said it would do, we would not have the threat of Russia or China testing kinetic ASATs as well as engaging in directed energy and radiofrequency interference, not to mention testing co-orbital ASAT and rendezvous and proximity operations. The current space deterrence construct and “diplomacy-first initiative” put into motion is based on hope as the strategy. Instead, we have a strategic reality of first-strike instability with the United States being placed further and further into a vulnerable position to surprise attack with no comparable capability to respond to such an attack.

| For many years following the release of the NSSS, disaggregation was considered to be the answer to many of the sustainability and “space protection” issues. |

Analysis: This is what the NSSS refers to as “deterrence by resilience” and what is now lumped under “Mission Assurance” by the Defense Department Space Policy office. The 2010 National Space Policy states the United States would “increase assurance and resilience of mission essential functions enabled by commercial, civil, scientific, and national security spacecraft and supporting infrastructure against disruption, degradation and destruction.”24 The goal of this was intended to confuse the “enemy’s targeting calculus” or, as the authors of the Atlantic Council report say, will “complicate an attacker’s abilities to degrade or defeat.” As a follow-on support document to the NSSS, an Air Force Space Command White Paper states that resilience is considered “as a deterrent…which may be the best way to…avoid an attack.”25 It is not a deterrent and may not be effective in maintaining mission assurance.26

Analysis: For many years following the release of the NSSS, disaggregation was considered to be the answer to many of the sustainability and “space protection” issues. Air Force Space Command wrote a white paper on this topic and many senior leaders began to reference it as the answer until the Government Accountability Office (GAO) published their assessment of disaggregation in 2014, which had a less supportive tone.

The GAO report, dated October 30, 2014, stated, “It is not yet known whether and to what degree disaggregation can help the Department of Defense (DOD)… increase the resilience of its satellite systems.” Following the report’s release, key members of Congress and the space policy arena began to backtrack from disaggregation as the panacea to all space protection and resilience questions. Now, the Atlantic Council appears to support bringing it back up as one of the “new” recommended courses of action that would “offload” national security missions to the commercial sector but in reality would put more of our critical space infrastructure at risk.27

It’s also interesting the authors state it’s probably a good idea to develop capabilities for “deterrence by punishment,” but that we should be transparent to the world of our intent to use them only as a “last resort.” In an offensive-dominant domain such as space, this implies only using them if attacked first. This will not work like the nuclear sphere, where there might be time to respond before the impact of the weapon. If the first strike is against US space assets is, as the Chinese put it, “rapid and destructive” as well as “multi-layered,” then a well-placed first strike could lead to a situation where last resort may need to be during enemy force posturing, especially for mobile ASAT assets. The concept the report is pushing is not deterrence and not new and innovative, and in reality is dangerous.

6. “Allow the U.S. government and industry the time and budgetary leeway to develop next generations technologies that might keep a leading edge in space, both for commercial benefits and military hedging of advantage”.28

Analysis: In many ways, this is almost like the “deterrence through response” NSSS concept, mixed with the Obama Administration’s attempt to make perpetual research and development (R&D) imply deterrence. That is not the case. “Budgetary leeway” is not the same as increased budgets for rapid testing, evaluation and deployment.

| The United States must address the growing threat to its space assets head-on instead of repeating the same actions over and over again and expecting a different result. |

Even though it might sound good giving industry and government players “budgetary leeway” and provide advocates of sound industrial and security policy more time to assess and try to convince people who are actively testing weapons to stop, we don’t control time and the perspectives of how a nation state perceives their interests—they may not always align with ours. As the old saying goes in military planning, “the adversary gets a vote,” and the potential adversaries of the United States have been voting for years for development, testing, and deployment. “Strategic restraint” is not mutual: it’s a one-way street leading to danger for the United States and its space assets. The United States does not have the luxury to repeat the same mistaken recommendations of the NSSS, which have not brought about stability but instead, ironically, first-strike instability, increased vulnerability, and more actors engaged in counter-space weapons development, deployment, and use. The passivity and lack of deterrent of the NSSS has created a new normal in the form of purposeful interference and attack in the radio frequency and directed energy arena known as “reversible counter-space.”

Conclusions

It is encouraging to see the Atlantic Council taking on the topic of improving the NSSS, but it is disappointing to see their approach did not have a broader background of authorship than two proponents of disarmament and passivity (called “rebalancing” in this report) when it comes to space defense. The Atlantic Council would have been better to consult a group of mixed backgrounds, including space control professionals and space policy leaders. That they didn’t made their report a rehash of old, ineffective concepts found in the present NSSS.

This report, and others of late, try to mask or treat the symptoms rather than address the problem at hand directly. Convincing allies to agree to something they aren’t engaged in already is a waste of time and political capital, especially if those allies are not going to bring anything of consequence to the table by way of enforcement and risk to the aggressors, creating the situation that prompted the discussion in the first place. The United States must address the growing threat to its space assets head-on instead of repeating the same actions over and over again and expecting a different result. Regrettably, this report does not promote a new vision, but repackages an old one, which has been proven ineffective. Why should we expect a different result by doing the same thing by calling it by another name?

Endnotes

- National Security Space Strategy. U.S. Department of Defense. 2011. P. 10

- “Toward a New National Security Space Strategy: Time for a Strategic Rebalancing”. Atlantic Council. June 2016. P. iii

- Ibid. p. iii

- Ibid. p. iii

- Ibid. p. iii

- Ibid. p. 25

- Ibid. p. 25

- Ibid. p. iv

- Ibid. p. 53

- Ibid. p. iv

- Ibid. p. 26

- Ibid. p. 26

- Ibid. p. v

- National Security Space Strategy. U.S. Department of Defense. 2011. P. 10

- Schulte, Gregory. “China and the New National Security Space Strategy”. Testimony before the US-China Security and Economic Review Commission. May 11, 2011. P. 3

- Schulte, Gregory. “Statement of Ambassador Gregory L. Schulte Before the Senate Committee on Armed Services, Subcommittee on Strategic Forces. May 11, 2011, p. 5

- Schulte, Gregory. “Protecting Global Security in Space”. Presentation at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Nanyang Technological University Singapore. May 9, 2012. P. 6

- National Security Space Strategy. U.S. Department of Defense. 2011. P. 3

- Schulte, Gregory. “Protecting Global Security in Space”. Presentation at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Nanyang Technological University Singapore. May 9, 2012. P. 3

- Hitchens, Theresa. “The Perfect Storm: International Reactions to the Bush Space Policy: High Frontier. AFSPC. March 2007.

- Josh Rogin, “Tauscher: We Will Get a Missile Defense Agreement with Russia,” The Cable, January 12, 2012

- Press Statement: Hillary Rodham Clinton on International Code of Conduct for Outer Space Activities. January 17, 2012

- According to Webster’s dictionary, Consensus means “a general agreement about something: an idea or opinion that is shared by all the people in a group.”

- National Security Space Strategy. U.S. Department of Defense. 2011. P. 11

- AFSPC White Paper: Resilient and Disaggregated Architectures.

- See the book Reversing the Tao: A Credible Framework for Space Deterrence by Christopher Stone for more analysis on NSSS view on space deterrence and its ineffectiveness.

- For further information on this, my previous article Security Through Vulnerability, provides some background on how this does not actively protect our capabilities.

- “Toward a New National Security Space Strategy: Time for a Strategic Rebalancing”. Atlantic Council. June 2016. pp. v