The new era of heavy liftby Jeff Foust

|

| “We still have a range for our launch window between September and November” of 2018 for the first SLS launch, NASA’s Hill said. |

That performance may soon be matched by China’s Long March 5, slated to make its inaugural launch late this year from the country’s new spaceport at Wenchang, on Hainan Island. However, by the end of the decade both may be eclipsed by no fewer than three vehicles, under development by NASA and two American companies, with much greater payload capacities. But the development of those vehicles raises questions about how much demand exists for such massive vehicles.

The best-known of those upcoming heavy-lift vehicles is NASA’s Space Launch System. Announced five years ago this month, after significant congressional prodding (see “A monster rocket, or just a monster?”, The Space Review, September 19, 2011), the initial Block 1 version of the SLS is now scheduled for launch in late 2018.

“We still have a range for our launch window between September and November” of 2018, said Bill Hill, NASA deputy associate administrator for exploration systems development, at a July meeting of the NASA Advisory Council’s human exploration and operations committee. “We have some challenges but we believe we can get there.”

Those challenges involve not just the SLS but also the Orion spacecraft and the ground systems needed to support SLS and Orion. Those working on SLS alone sounded more optimistic about being ready for launch. “The SLS is a rocket that is going to be ready in less than two years,” said Boeing’s Benjamin Donahue in a talk last week at the AIAA Space 2016 conference in Long Beach, California. “It’s well on its way to first flight.”

NASA and its contractor team are working to make that 2018 flight the only one of the Block 1 version. They hope to have ready for the next SLS mission—and the first to carry a crew—the upgraded Block 1B version, with a payload capacity to LEO of more than 100 metric tons. That version will replace the interim upper stage used on the Block 1 with a new, and more powerful Exploration Upper Stage (EUS).

Design studies of the EUS are underway now at Boeing, Donahue said, with the current design using four RL10 engines versus the one RL10 in the Block 1 upper stage. “That much larger upper stage is really going to optimize the capability of the core stage” of the SLS, he said. “It’s going to capture much more missions because of its increase in capability.”

The Block 1B is shaping up to be a workhorse for cislunar exploration in the 2020s (assuming, of course, that the SLS program survives the upcoming transition in presidential administrations.) The extra capacity offered by the Block 1B, plus volume provided by a stage adapter between the Orion and the EUS, will allow those launches to “co-manifest” additional hardware, like modules for a cislunar habitat that figures into NASA’s current “proving ground” plans for human missions in the next decade.

Ultimately, NASA plans to develop the SLS Block 2, with advanced boosters, capable of placing 130 metric tons into LEO. But while both NASA and Congress have deemed the Block 2 version of SLS essential for human missions to Mars, its development remains uncertain. “The big Block 2 would be available maybe in the 2030s,” Donahue said.

But before the SLS makes its first flight in its Block 1 configuration, another heavy-lift vehicle is set to finally make its debut. SpaceX has been working for several years on its Falcon Heavy, which, analogous to the Delta IV Heavy, uses three first stage cores with a single second stage. The vehicle will be able to place up to 54 metric tons into low Earth orbit, making it the “the most capable rocket flying,” SpaceX says on its website—at least until the SLS flies in late 2018.

| “Sorry we’re late,” SpaceX’s Shotwell said of the Falcon Heavy. “This is actually a harder problem than we thought.” |

Of course, Falcon Heavy needs to start flying first. When SpaceX announced the Falcon Heavy in 2011, the company planned to deliver the first vehicle to Vandenberg Air Force Base in California by the end of 2012 for launch in early 2013. That launch date has slipped significantly because of technical issues as well as a focus on ramping up the Falcon 9 flight rate—particularly after the June 2015 Falcon 9 launch failure. The launch also moved to Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Complex 39A, which SpaceX is renovating for Falcon Heavy and commercial crew Falcon 9 missions.

“Sorry we’re late,” said SpaceX president Gwynne Shotwell in a speech last month at the AIAA/Utah State University Conference on Small Satellites in Logan, Utah. “This is actually a harder problem than we thought.”

SpaceX now says its Falcon Heavy will make its first launch no earlier than the first quarter of 2017. (credit: SpaceX) |

At the time, SpaceX was still planning to make the inaugural Falcon Heavy launch before the end of the year. But the September 1 pad explosion that destroyed a Falcon 9 rocket prior to a static fire test has put those plans on hold, as the company continues to investigate the cause of the accident.

“We plan to fly the Falcon Heavy as soon as the first quarter of 2017,” Lars Hoffman, senior director of government sales at SpaceX, said at AIAA Space 2016 last week. That launch, he said, would include an attempt to land all three booster cores, most likely back at the Cape Canaveral “Landing Zone 1” the company used for landing Falcon 9 first stages last December and again in July. The company, he said is building additional landing pads at the site to accommodate multiple landings.

That schedule, though, depends on the outcome of the ongoing investigation, about which SpaceX has released few details since shortly after the accident. “It’s too early to tell, honestly, whether or not it’s going to impact the Falcon Heavy schedule,” Hoffman said.

Then there’s the latest entrant in the heavy-lift sweepstakes: Blue Origin. Last week, company founder Jeff Bezos sent out a newsletter announcing the orbital launch vehicle the company has been talking about developing for more than a year: New Glenn.

“Named in honor of John Glenn, the first American to orbit Earth, New Glenn is 23 feet [7 meters] in diameter and lifts off with 3.85 million pounds of thrust from seven BE-4 engines,” Bezos wrote, adding that the first stage would be designed to land for reuse. The rocket’s second stage would use a single BE-4 engine, while an optional third stage would use the BE-3 engine that currently powers the company’s New Shepard suborbital vehicle.

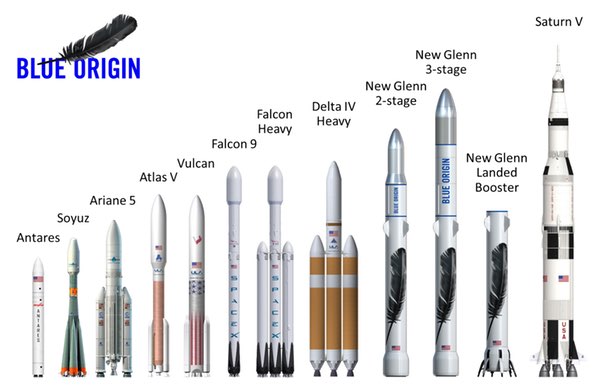

The announcement played up the physical size of New Glenn, noting that its three-stage variant would be 313 feet (95.4 meters) tall. An illustration provided by Blue Origin showed the New Glenn standing alongside a gallery of other vehicles, towering over all but the Saturn V (although noticeably absent from the lineup was any version of NASA’s SLS.)

Also missing from the announcement was any discussion of “how much,” either in how much a New Glenn launch would cost or how much payload it could carry. Engineers scrutinizing the limited details about New Glenn provided in last week’s announcement estimate it could place 50 to 70 metric tons in low Earth orbit. Blue Origin president Rob Meyerson, in a brief interview during the AIAA Space 2016 conference last week, declined to give details about its performance, saying the company would release more details about New Glenn later this year.

New Glenn will be ready for its first launch by the end of the decade, Bezos said in his announcement. That means that, before the SLS can make its second launch (no earlier than August 2021 but perhaps as late as 2023), there will be two other heavy-lift vehicles with payload capacities approaching the initial SLS Block 1 vehicle. Just who needs that kind of performance?

| “I’m not a big fan of commercial investment in large launch vehicles just yet,” Bolden said. |

Both Bezos and SpaceX’s Elon Musk are motivated by long-term visions of space exploration and settlement, but both presumably desire to generate revenue in the near term with their heavy-lift vehicles. What sort of demand might exist for these vehicles, and at what prices, ventures into uncharted territory.

There’s also some government skepticism about commercial development of such vehicles. “We believe that our responsibility to the nation is to take care of things that normal people cannot do or don’t want to do, like large launch vehicles,” NASA administrator Charles Bolden said during an AIAA Space 2016 panel session. “I’m not a big fan of commercial investment in large launch vehicles just yet.”

That statement, just a day after Bezos’ announcement, raised eyebrows. But Blue Origin’s Meyerson downplayed any sense of a rift between the company and NASA about its launch plans, saying he felt NASA supported their efforts despite Bolden’s statement.

In another panel session at the conference two days later, Bill Gerstenmaier, NASA associate administrator for human exploration and operations, mentioned the rocket positively. “That’s another piece that potentially maybe gives us another way to get crews to space,” he said of New Glenn.

And New Glenn won’t be the last heavy-lift launch concept to appear from industry. At next week’s International Astronautical Congress in Mexico, Musk is scheduled to give a long-awaited talk outlining his Mars exploration architecture. That’s expected to include a heavy-lift vehicle that’s been dubbed “BFR”: “B” for “big” and “R” for “rocket.” (The meaning of “F” is left as an exercise for the reader.) That will likely make use of the Raptor methane engine that SpaceX is developing.

But Blue Origin isn’t done, either. “Our vision is millions of people living and working in space, and New Glenn is a very important step. It won’t be the last of course. Up next on our drawing board: New Armstrong,” Bezos wrote last week. “But that’s a story for the future.”