Albedo 0.06: Vangelis returnsby Dwayne A. Day

|

| There has long been a connection between electronic music and depictions of spaceflight. |

Vangelis achieved his broadest recognition when he won an Academy Award in 1981 for best original score for the film Chariots of Fire. A modern synthesizer score was an odd but inspired choice for a film about runners in the 1924 Olympics, and when the theme was released as a single in 1982 it briefly topped the Billboard charts. Vangelis scored several other movies throughout the 1980s, including Blade Runner, Missing, and Mutiny on the Bounty, and his music appeared in others like The Year of Living Dangerously. Even today some electronic music aficionados still bemoan the fact that he has never released the complete Blade Runner soundtrack.

Vangelis’ work influenced other composers and contributed to wider acceptance of synthesizer music in films. Synthesizers had been used for other movies, notably Tangerine Dream’s score for the 1977 film Sorcerer. But Vangelis’ sound and his success undoubtedly allowed electronic music to reach wider audiences—Tangerine Dream’s ominous score for the 1983 movie Risky Business was also part of this movement, and today is enjoying a bit of a renaissance. Unfortunately, the advent of inexpensive electronic keyboards resulted in a lot of inferior electronic music infecting television programs for the rest of the 1980s. Vangelis contributed the score for the 1992 movie 1492: Conquest of Paradise, but his film collaborations became more sporadic in later years.

There has long been a connection between electronic music and depictions of spaceflight. The ethereal electronic sounds of an early synthesizer called a ring modulator provided background to the 1956 classic Forbidden Planet, and the electronic instrument known as the Theremin was often used as background in both science fiction and horror movies.

Electronic scores have also been used in planetarium shows for decades. Various pieces from Albedo 0.39 were used in planetarium shows as well as Cosmos. Tangerine Dream’s Force Majeure, released in 1979, also became a common choice for planetarium shows. This relationship has to do with many things, including electronic music being perceived as futuristic—musicians often work behind banks of monitors and buttons as if piloting a spaceship—as well as the ability of electronic synthesizers to produce sounds that evoke the mystery and wonder of outer space. Ambient artists themselves have long been influenced by spaceflight and the night sky. French electronic music composer Jean-Michel Jarre befriended astronauts Ronald McNair and Bruce McCandless while preparing for a major concert in Houston. Jarre composed a piece that was to include saxophone played by McNair aboard the space shuttle Challenger while in orbit. The January 1986 accident and McNair’s death almost curtailed the concert, but Jarre was encouraged by McCandless to continue it, with another saxophonist playing McNair’s solo. Jarre retitled the piece Last Rendez-Vous (Ron’s Piece) and dedicated it to the fallen Challenger astronauts.

| Just this past summer the Juno mission arrived at Jupiter shortly after several artists released Jupiter-inspired works via Apple Music. |

There are different genres of electronic music, but Vangelis and similar composers generally fall into what is commonly referred to as ambient music. Starting in the early 1970s, a former architect named Stephen Hill began hosting a weekly late-night radio program in the San Francisco Bay area called Music From the Hearts of Space, which became the most popular contemporary music program on public radio stations in the United States, regularly featuring works by Vangelis. (See: “Cruising through the cosmos on waves of sound”, The Space Review, May 13, 2013.)

Ambient music has evolved over many years. Whereas the space theme has never gone away, some composers, like the mind-blowing Steve Roach, have sought to take their music to deeper places, tribal, even primitive. Some of Roach’s compositions border on primordial, to the point where the viewer feels like they are being transported into the Earth, or back through evolution.

Earlier this year, the Cartoon Network aired an inspired bit of programming poking fun at electronic music and its penchant for seriousness and cosmic visions. Called Live at the Necropolis: Lords of Synth, it was an 11-minute film portrayed as a long-lost videotape recording from a 1986 public television program featuring an epic concert battle between three synthetic music legends: Xangelix (guess), Morgio Zoroger (i.e. Giorgio Moroder), and Carla Wendos (i.e. Wendy Carlos). They meet to compete to score the arrival of Halley’s Comet, with the winner being anointed “The Lord of Synth” and the losers being “banned from music for a period of one hundred years.” Xangelix is billed as “a reclusive genius who has appeared in public only… never.” Zoroger and Wendos are “former lovers,” which occurred sometime after Wendos transitioned from being a man. When the comet changes direction and heads towards Earth, the rival musicians must set aside their differences and battle it with their synthesizers, achieving a higher level of existence in the process. Xangelix is shown prophetically saying that “there is only one hope for humanity: the synthesizer.” (Not quite as good as Zoroger’s introduction: “a devil-may-care playboy who drinks a lot, even for an Italian.”) Like all great parodies, the writers had to love their subject to skewer it so effectively.

In 2001 Vangelis performed his orchestral choral symphony Mythodea. NASA used the music to promote its Mars Odyssey mission. NASA has used music on rare occasions to celebrate its space missions. The final space shuttle mission, STS-135, had a fanfare (which apparently has not been publicly released) composed by maestro Bear McCreary. Just this past summer the Juno mission arrived at Jupiter shortly after several artists released Jupiter-inspired works via Apple Music. These include Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’ weirdly atmospheric Juno and Zoé’s Panspermia and several other works that accompanied the short film Visions of Harmony.

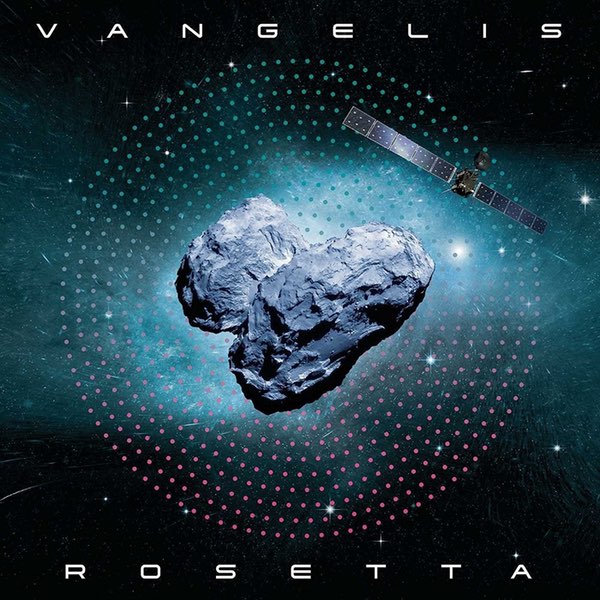

Around the time that the Juno works were released, word of Vangelis’ Rosetta soundtrack emerged. The release date slipped slightly, apparently so that it could debut on the same day that the plucky spacecraft finally ended its mission and set down on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. The European Space Agency’s $1.6-billion Rosetta mission has been highly productive, and scientists will be analyzing its data for years. But the program team also deserves accolades for its public outreach. They kicked off the mission with a clever video, Ambition, showing people of the future discussing the formation of the solar system and the role comets played in it, and then a series of wonderful animated cartoons telling the story of Rosetta and its tiny lander Philae. The NASA/Caltech Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California has long set a high bar for public outreach for planetary missions, but ESA’s Rosetta team has rivaled them. A year ago, ESA released several videos about the comet rendezvous featuring Vangelis’ original music. Later the musician announced he would release an entire soundtrack about the mission. An extended trailer was released in early September.

| The NASA/Caltech Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California has long set a high bar for public outreach for planetary missions, but ESA’s Rosetta team has rivaled them. |

Rosetta the album features thirteen tracks with titles like “Origins (Arrival),” “Philae’s Descent,” and “Albedo 0.06”—the latter an indication that Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko is far darker than Earth. Comets may light up the night sky, but relatively speaking their surfaces are extremely dark. The title track “Rosetta” has echoes of Alpha, which was memorably used in Cosmos to accompany an animated depiction of the development of life on Earth. Considering the theories that comets may have played a role in the formation of life on Earth, that was probably not coincidental. Many of the works are quite descriptive, evoking the spacecraft and its actions. This is certainly true of the final track, Return to the Void. Now that Rosetta has been turned off and its comet heads out into the colder reaches of our solar system, it could have no finer tribute than Vangelis’ electronic sounds, singing to it on its journey back into the dark.