Fallen star: John Gresham, 2016by Dwayne A. Day

|

| He told me how the Air Force’s Manned Orbiting Laboratory program was canceled one day and, the following Monday, three houses went up for sale on his street. He finally knew what his neighbors did for a living—they had been building the expensive and mysterious manned intelligence satellite. |

I first met John in the late 1990s through a mutual friend who had served as an engineering fellow on the House Science Committee advising on space issues. But we didn’t really become friends until about six years ago when we started going out to sushi dinners every couple of months, where we would endlessly discuss space and military subjects. John was incredibly well-read and well-informed, although health issues affected his mobility in the past decade and prevented him from traveling much. He was whip smart, and although he was not a space expert and did not regularly read and research that subject, he had an ability to connect issues even if they were new to him, which made him very good at interviewing people. He had good stories to tell, and some of the best ones were how his life had intersected with the space program.

John was a young boy living in southern California in the late 1960s and several of his family members were in the aerospace business, including an aunt who worked for NASA public relations and a father who, I think, worked for North American Aviation. Because of these ties, he was able to meet many of the Apollo-era astronauts as a kid. He told me how the Air Force’s Manned Orbiting Laboratory program was canceled one day and, the following Monday, three houses went up for sale on his street. He finally knew what his neighbors did for a living—they had been building the expensive and mysterious manned intelligence satellite. He had also learned a lesson about how fickle the aerospace engineering field could be.

John took some college classes, but never obtained a degree. Like many people, he taught himself computer programming and managed to get a job in the early 1980s in the computer field. He told me a story about how one of his first jobs was as a contractor maintaining computer systems that were operated by various companies. I cannot remember if these were early personal computers running basic engineering software or a step down from mainframe computers used for checking out electronics systems.

He recounted how one day he was sent to a big aerospace company with a balky computer. I really don’t remember the details of his story, like where he went, but I think it was to Lockheed’s satellite facility in Sunnyvale, California. According to John, the computer was in a classified facility, but he did not have a security clearance. He was blindfolded and escorted into a large room and, when he was allowed to remove the blindfold, he found himself in an area that was surrounded by portable curtains, the kind you might see in a hospital room. They blocked the view on all four sides. In the center of this temporary structure was the malfunctioning computer. John sat down at the terminal and did his magic and got it fixed. He was then blindfolded again and escorted out of the facility, never having seen what was on the other side of the curtain. All he could guess was that it was big.

| John got to drive an M-1 tank, which he used to knock over trees at an Army base. He said that perhaps the neatest thing he did was fly the simulator for the stealthy Comanche helicopter. |

When John told me this story several years ago, he said that he suspected that what was behind the curtains was a HEXAGON reconnaissance satellite under construction. I think he had read that the HEXAGON was assembled at the location where he had been sent, and his visit in the early 1980s was at a time when the last HEXAGONs were being built. I didn’t know the answer, and suggested that he talk to my friend Phil Pressel, who had designed the HEXAGON’s sophisticated camera system for Perkin-Elmer Corporation. But John never called him, and I doubt that Phil would have known without more details.

John was always reading, always acquiring books, and he told me a story about another early job he had. He had been hired by a defense contractor to work on the Tomahawk cruise missile that was then being mounted on US Navy battleships. Tomahawk came in several variants, including conventional and nuclear. After being hired, John had to wait for his top secret security clearance before he could take on more substantive work. He waited and waited and waited. Finally, it was approved, and he went to his boss and said, “Okay, what is the vital piece of information that I needed the clearance to know about?” The boss opened up a safe, took out a booklet, opened it and showed John: the thing John had waited so long for his clearance in order to learn was the yield of the Tomahawk’s W-80 thermonuclear warhead. John laughed, and the next day he brought in a book from his home library, opened it up, and showed his boss the exact same information, already in the public domain. As it turned out, John’s work never involved the warhead, so he could have done the job without ever knowing that information.

At some point John gave up being a defense contractor to become a writer and editor. He wrote an article about the Soviet Yak-38 Forger vertical takeoff aircraft for the US Naval Institute’s Proceedings magazine. Tom Clancy read the article and contacted John about it. By the early 1990s Clancy had become a brand, producing numerous books and branching out into video games—all Clancy had to do was put his name on something and it turned to gold. I don’t know for sure, but I think that John was essentially Clancy’s ghost writer for a series of non-fiction books in the 1990s such as Carrier, Submarine, and Armored Cav. Clancy’s name on the cover made the books best-sellers, and John got access to all kinds of things because Clancy made a phone call and the military opened the gates. John accompanied him to take notes. John got to drive an M-1 tank, which he used to knock over trees at an Army base. He said that perhaps the neatest thing he did was fly the simulator for the stealthy Comanche helicopter.

He told me a few stories about Clancy, such as his falling out with his original publisher, who had been cheating him on royalties for the bestselling The Hunt For Red October—and had apparently sent Clancy a big fat check to prevent a lawsuit and negative publicity. But Clancy had a reputation for being mercurial, and I never really asked about their working relationship. After all, I had plenty of time to do so, right?

| I have found numerous titles that I never knew existed—books on obscure aircraft, or foreign titles you would never find at a Barnes & Noble. Each time the purchase is somewhat bittersweet—I wish that I could have discussed that subject with John. |

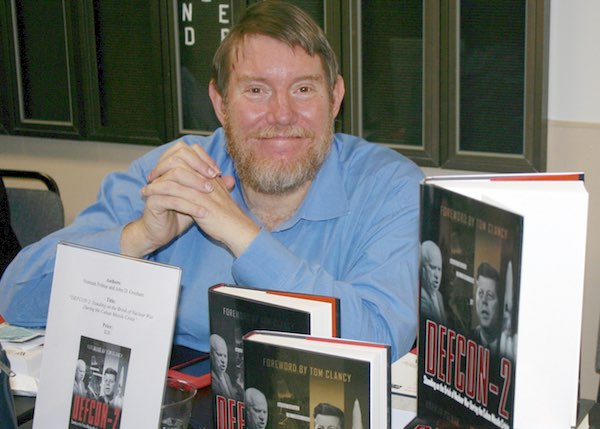

For the fiftieth anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis, John co-wrote a book with Norman Polmar called DEFCON-2, on the high state of readiness adopted by the US military during the incident. In the 1990s, when numerous facts about the crisis were declassified in the United States, Russia, and Cuba, I read about the subject extensively and found it fascinating. Some of the new information was startling, such as the fact that the Soviets already had tactical battlefield nukes in Cuba and would have used them to repel any American invasion of the island.

After the publication of John and Norman Polmar’s book, we were discussing various aspects of the time when the world was on the brink of nuclear war. John wanted to know if I was aware of any satellite operations that were relevant to the crisis. I didn’t know of anything substantive, and I skeptically asked John if there was much left to tell about the Missile Crisis after all the revelations and the publication of dozens of books. Without skipping a beat John rattled off several major aspects of the Missile Crisis that still remained classified, including many of the military mobilizations and operations that had occurred, and some of the high-level political discussions. There are a lot of things about the Cuban Missile Crisis that we still do not know despite all the scrutiny.

It’s funny how you can know somebody for years and suddenly learn something new about them. A couple of years ago I mentioned in a Facebook post that I had a collection of interview transcripts of people associated with the first satellite reconnaissance program, named CORONA. They had been produced for a pair of 1996 documentaries called “Secret Satellite” and “Spies Above.” A film crew had conducted the interviews, and then they had commissioned transcripts that the writing team used to assemble the narrative for the two documentaries. After the programs had aired (I think on The Discovery Channel) somebody had passed the unneeded transcripts to me.

Within minutes of making my post I got an excited phone call from John. Apparently he had worked on the production of numerous documentaries over the years, primarily ones with military themes, but also some about space. Often he would appear as an expert in shows that he had helped write. It turned out that he had worked for Arcwelder Films, which produced the satellite documentaries, and he remembered the transcripts they had produced. He said that he remembered how disappointed he had been at the time that so much valuable information was destined to be tossed in the trash. He was thrilled to learn that they had been preserved, and in fact had ended up in the hands of somebody he trusted to use them well.

| You may have noticed that 2016 has been a pretty awful year nationally and globally. I’m no pessimist, but unfortunately, there’s no reason to believe that 2017 will be better than 2016. No reason to believe it will be more stable and people will be more civil to each other. |

And even though John is gone, I’m still learning things about him. I never visited his apartment, but friends told me that his library included more than 3,000 books. After his death, his massive collection of mostly military books went to a used bookstore, and I’ve been visiting there and looking through and buying a number of them. I have found numerous titles that I never knew existed—books on obscure aircraft, or foreign titles you would never find at a Barnes & Noble. Each time the purchase is somewhat bittersweet—I wish that I could have discussed that subject with John. Very early this year John had loaned me his copy of Mike Jenne’s novel Blue Gemini (see “Review: Blue Gemini”, The Space Review, March 28, 2016), making me promise to return it after I read it. John had recently interviewed Jenne on his Internet program, and wanted to know what I thought of the book. I never got the opportunity to tell him. I still have the book.

You may have noticed that 2016 has been a pretty awful year nationally and globally. It’s been bad for me personally. Two people that I worked with in the space field, Patti Grace Smith and Molly Macauley, died this year, Molly under particularly disturbing circumstances. Even though the calendar is just the way we mark time and does not affect events, we all look forward to the end of a bad year. I’m no pessimist, but unfortunately, there’s no reason to believe that 2017 will be better than 2016. No reason to believe it will be more stable and people will be more civil to each other. It would be good to sit at a table eating sushi and talking about the space program with John, but he was another casualty of this wretched year. Adios, 2016, and good riddance.

My friend Mike Markowitz, who knew John far better than me, told me that John could at times be irresponsible (he apparently never met a deadline he didn’t miss), but he also had an unfailing optimism and a big heart. After John’s death, many people told him that John had saved their lives at some point in the past. Mikey noted that his rabbi teaches that saving a life is the way you save the world, and John did that many times over. At Thanksgiving we’re supposed to reflect upon and give thanks for the important things in our lives. I’ll have to give a toast to John Gresham. He’s not here anymore, but I’m thankful that I knew him.