Two years to go for James Webbby Jeff Foust

|

| “We’re celebrating the fact that our telescope is finished and we’re about to prove that it works,” Mather said. |

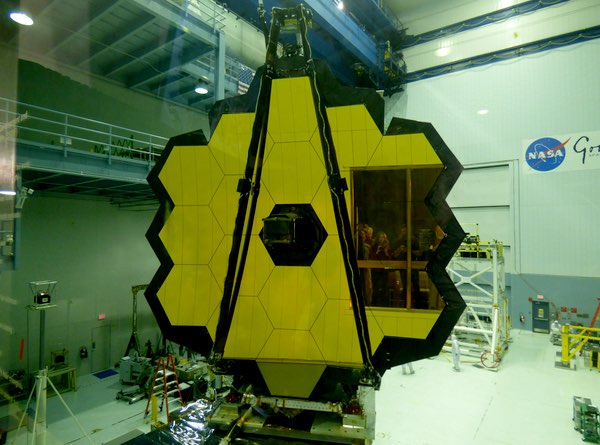

Media arriving earlier this month at an observation gallery at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, overlooking the clean room where elements of the James Webb Space Telescope are being assembled, couldn’t help but notice the mirrors. The telescope’s primary mirror, assembled earlier this year from 18 hexagonal segments of gold-coated beryllium, was in the vertical position, facing the windows. People gravitated to the windows, taking all manners of selfies with the mirror in the background, or simply images of the mirror itself, capturing reflections of themselves in the process.

The reporters at the event were not there to just take pictures. NASA invited them to announce the latest progress in the development of the observatory that, if all goes well, will launch in two years to the Earth-Sun L-2 point, 1.5 million kilometers from the Earth.

“Welcome to our science party here today,” John Mather, the Goddard astronomer who is the senior project scientist for Webb, told the standing-room-only crowd that squeezed into the small observation gallery on the morning of November 2. “We’re celebrating the fact that our telescope is finished and we’re about to prove that it works.”

That statement was a mild exaggeration. What was on display beyond the windows was not the full spacecraft but the business end of the observatory, so to speak: the mirrors and, integrated inside, its science instruments, a collection known as the Optical Telescope element and Integrated Science (OTIS) assembly. They are the most visible, and most scientifically important, part of Webb, but hardly the whole spacecraft.

OTIS, though, is finished, and ready to begin testing. The media event coincided with a test known as “center of curvature” to test the alignment of its optics. The assembly will soon begin a series of tests at Goddard to simulate the rough launch environment it will experience: placed in a chamber and blasted with speakers to model the acoustic environment inside the rocket’s payload fairing, and put on a special table and shaken to reproduce the vibrations of launch. Then, NASA will run the center of curvature test again to ensure that the optics are in good shape.

Early next year, OTIS will travel from Goddard to the Johnson Space Center, where an Apollo-era vacuum chamber has been refurbished. The telescope system will undergo thermal vacuum tests there to ensure the optics work properly in the space environment. From there, it will go to Northrop Grumman’s facilities in Southern California to be united with the spacecraft bus and its giant sunshade, and undergo additional tests before a two-week boat journey in 2018 to French Guiana for launch on an Ariane 5.

Five years ago, there were doubts Webb would ever get this far. The program had long suffered from cost overruns—during his time in office, former NASA administrator Mike Griffin famously said the observatory was “undercosted”—but another overrun and schedule delay in 2011 appeared for many to be the final straw. House appropriators threatened to withhold funding for Webb. “Some of you who have followed JWST know it almost didn’t happen,” said NASA administrator Charles Bolden at the media event.

Only a last-ditch effort by NASA, elevating the telescope to an “agency priority” with revamped management and a dedicated funding line—and spending cap of $8 billion—secured its future. “We made a commitment to the president and the Congress, namely, Sen. Barbara Mikulski,” Bolden said, referring to the Maryland Democrat who was a key figure on the Senate Appropriations Committee and concerned about a project involving facilities in her home state.

NASA administrator Charles bolden and John Mather, the senior project scientist for JWST, speak at a November 2 briefing. (credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky) |

Since that effort, known as the “replan,” five years ago, work on Webb has stayed on track. Scott Willoughby, Northrop Grumman vice president and program manager for Webb, said that the overall program was maintaining the projected schedule margins set by the 2011 replan.

| “We are on plan when it comes to cost,” Ochs said. “We are on schedule.” |

“That line was drawn to maintain more schedule margin than a typical NASA program, because it’s Webb and we knew there would be additional complications,” he said, referring to a chart that showed the projected schedule margin over time for the project. “We’re right in line to where we need to be at this point in time, with two years to go before launch.”

“We are on plan when it comes to cost. We have not exceeded the cost budget,” Bill Ochs, the Webb project manager at NASA said. “We are on schedule. We have held an October 2018 launch date since the replan.” He added that the three major elements of Webb—OTIS, the spacecraft bus, and the sunshield—were all within about a month of being on the critical path for the overall project.

Of course, all that good planning could be upset by problems during that testing process. Better, though, to find those problems while the spacecraft is still on the ground because, unlike Hubble, Webb is not designed to be serviced after launch.

After some confusion at the briefing, though, NASA officials didn’t entirely rule out the possibility that it could be serviced in some kind, but suggested it was highly unlikely. Ochs said that Webb’s launch interface ring, which connects the spacecraft to the launch vehicles, will have targets added to aid in any docking by a future spacecraft.

| “I think the story we have to tell, the record of performance that we have, should stand us in good stead,” Bolden said. |

At the same time, they suggested any servicing would be unlikely. “There’s no plans for anything needing servicing for the mission,” said Eric Smith, the Webb program manager at NASA headquarters. “If the unthinkable happens and we have to do something, it would require an entire design effort for such a mission. At that time, the agency would have to make a decision about whether it’s worth going up there.” It would, he said, depend on exactly what went wrong with the spacecraft and the feasibility, and cost, of repairing it.

“It’s critically important to get it right here on the ground,” Bolden said. He acknowledged, though, that future spacecraft would be designed differently. “This may be the last telescope that we build that is not modular, such that it has a capability to be serviced on orbit.”

But, for now, NASA is confident that all will go well for Webb, given the progress they’ve made in the last five years keeping the mission on budget and on schedule. The event was something of a grand finale for Bolden, who will leave NASA at the end of the Obama Administration in January; he suggested the event came together after he asked Smith about an opportunity to see the telescope one more time.

“We think we have an incredibly good story to tell” the next administration, he said in comments prior to the November 8 election of Donald Trump. “James Webb has stood the test of time. We spent a tremendous amount of money up front.”

“We have done what I have always said about NASA: we told people what we were going to do, we made a commitment of a schedule and time, and we have been on that for about six years now,” he continued. “I think the story we have to tell, the record of performance that we have, should stand us in good stead.”

Missing from the event was Mikulski, who is also leaving Congress at the end of this year. Bolden predicted that, even in retirement, Mikulski would continue to keep tabs on the progress of the space telescope she helped shepherd through Congress. “My guess is, when I am no longer the NASA administrator after the Obama administration and she is no longer active senator Barbara Mikulski, she has my number and she will probably still be calling and saying, ‘What are those guys doing?’” he said.

| “In a couple more years we should be at the launch site in French Guiana, ready to push the button,” Mather said. “Wish us well.” |

Meanwhile, Mather, who shared the Nobel Prize in physics in 2006 for using NASA’s COBE spacecraft to discover minute variations in the cosmic microwave background that provided more evidence of the Big Bang, is looking forward to the science that Webb will ultimately be able to do.

Asked by a reporter what he thought Webb’s “most exciting” observation would be, Mather replied, “If I really knew, I’d tell you. I’m hoping that we’ll find something nobody knows is out there.” The potential discoveries, he said, range from understanding of the early universe to planets in our solar system.

He recalled a mid-1990s committee that examined what science a successor to the Hubble Space Telescope could perform, a process that ultimately led to the development of the James Webb Space Telescope, now approaching launch. “In a couple more years we should be at the launch site in French Guiana, ready to push the button,” he said. “Wish us well.”