Asteroid Discoveryby Jeff Foust

|

| “These small bodies really are the fossils of planet formation,” Levison says of the Trojan asteroids. |

Those five finalists couple be grouped into two classes. Three of the missions were devoted to asteroids of various types: Lucy and Psyche would travel to asteroids, while NEOCam would observe near Earth asteroids from the vicinity of Earth. The other two missions, known by the acronyms DAVINCI and VERITAS, would travel to Venus, a planet not visited by NASA since the early 1990s.

With two missions to be picked, the conventional wisdom was that NASA would pick one asteroid mission and one Venus mission. That was particularly heartening to the community of Venus scientists, given the long drought in missions (see “For planetary scientists, Venus is hot again”, The Space Review, December 12, 2016).

So much for conventional wisdom. Instead of that expected split, NASA instead doubled down on the asteroids, selecting Lucy and Psyche for development. It also kept hope alive for NEOCam, extending a Phase A study of the mission by a year to revise the spacecraft concept.

Meet Lucy and Psyche

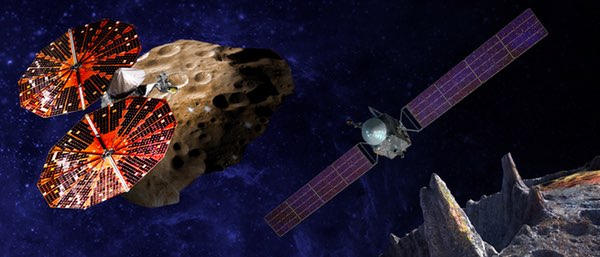

The first of the two new missions to fly will be Lucy. Scheduled for launch in October 2021, it will head out to a group of asteroids known as Trojans located at the L-4 and L-5 Lagrange points on either side of Jupiter. Lucy will be the first mission to explore these asteroids, which may be unaltered remnants from the formation of the solar system.

“One of the really surprising aspects about this population is its diversity,” said Harold Levison, principal investigator for the mission at the Southwest Research Institute. “We believe that’s telling us something about how the solar system formed and evolved. These small bodies really are the fossils of planet formation.”

His use of the term “fossil” was deliberate: the name Lucy, he said in a press briefing about the Discovery mission selection, is not an acronym but is instead taken from the famous human ancestor fossil.

Lockheed Martin will be the prime contractor for Lucy, and will borrow from a number of previous NASA missions it has developed, including the OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample return spacecraft and Juno misson to Jupiter. That includes experience with large solar arrays needed to generate power at Jupiter’s distance from the Sun.

| With the Psyche mission, said Elkins-Tanton, “we can literally visit a planetary core, the only way that humankind ever can.” |

Getting there, though, is novel to Lucy. “This trajectory is amazing,” said Tim Halbrook, Lucy flight systems deputy program manager at Lockheed Martin, in an interview. Lucy will use three Earth gravity assists and five deep space maneuvers to get into a six-year heliocentric orbit that takes it through one set of Trojans in 2027 and another in 2033. That trajectory requires a launch in a three-week window from mid-October to early November 2021, with a backup window about one year later.

Psyche, the other mission, will launch in 2023 and make flybys of the Earth and Mars in 2024 and 2025, respectively, before arriving at the asteroid the spacecraft is named after in 2030. The asteroid, the largest metallic body in the asteroid belt, is thought to be the core of a planet that broke apart during the formation of the solar system.

“We have never seen a metal world,” said by Lindy Elkins-Tanton of Arizona State University, the principal investigator for Psyche. Studying Psyche has obvious scientific interest—“we can literally visit a planetary core, the only way that humankind ever can” with the mission, she noted—but could also provide insights for future asteroid miners.

The Psyche spacecraft will be built by Space Systems Loral (SSL), a company that only recently has turned its attention to the US government market after, for years, focusing primarily on building large communications satellites for commercial customers.

Having SSL involved on a NASA mission is an additional benefit, argued Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA associate administrator for science, in an interview the day after the Discovery announcement at the 229th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Texas. “It brings another industrial partner into the mix,” he said. “I think that’s really good for us as a nation.”

The curious case of NEOCam

While the selection of two asteroid missions was surprising to many who expected an asteroid-Venus split decision, what was just as puzzling was NASA’s decision to offer a one-year extension of a Phase A study to NEOCam, a mission to look for near Earth asteroids that could pose an impact risk to the Earth.

| NEOCam’s future might lie outside of the Discovery program, said Zurbuchen. “I’m trying to see what the opportunities are.” |

“It is really an acknowledgement that even though it was not selected for a full, complete implementation, we want them to address issues that were identified in the Discovery evaluation process,” said Jim Green, head of NASA’s planetary science division, at the NASA briefing announcing the Discovery awards. He did not elaborate on what those issues were.

Zurbuchen, in the later interview, said there were two objectives behind his decision to extend the NEOCam study. One was to address those issues with the proposed spacecraft, and the other was to see how NEOCam might fit into NASA’s broader planetary defense efforts.

He suggested that NEOCam’s future might lie outside of the Discovery program, saying that changes the new administration might make to NASA could give another chance for NEOCam. “I’m trying to see what the opportunities are.”

Green offered a similar assessment a week later at a meeting of NASA’s Small Bodies Assessment Group (SBAG). The extended study, he said, “enables it to get near ready for selection,” although the planetary science program would have no funding for it at the end of the study. “It basically allows us to look for the funding and see what happens within this next administration.”

Discovery’s future

Many people in the planetary science community, after hearing the NASA announcement, continued to wonder why the agency went all-in on asteroids, picking two asteroid mission proposals and funding a third for additional study, shutting out the Venus proposals.

Green, in the briefing announcing the awards, argued that NASA chose Lucy and Psyche based on the science they offered. “The Discovery program is a competition,” he said. “In that competition, we’re looking for top science, top scientific implementation, minimizing our technical risk.” He didn’t elaborate on what specifically set the two winning missions apart from their competitors.

Zurbuchen, who formally made the selection of Lucy and Psyche, said he looked at various combinations of other missions before settling on those two, including picking one or both Venus missions. He said budget and schedule issues kept him from doing so. “That was not possible. I tried,” he said.

“Unfortunately, these missions did not receive the level of evaluation that the top two missions that we selected,” Green said of the Venus missions at the Discovery award briefing. He added, though, that the call for proposals released in December for the New Frontiers program does include a Venus mission as one of six options.

The Venus missions could also wait for the next Discovery round. Green said that with this selection place, they now plan to resume future selections about every three years. Prior to these two awards, the last Discovery mission selection came in August 2012, when NASA selected the Insight Mars lander mission, whose 2016 launch was postponed to 2018 because of problems with an instrument.

“We’re going to try and get the program back into a cadence that’s much like what was recommended in the planetary decadal,” Green said, referring to the once-a-decade assessment of planetary science mission priorities. “We’re probably on the order of a 32- to 36-month cadence.”

But for now, asteroids reign supreme in the Discovery program. “You guys can kind of feel like you cleaned the table,” said Lindley Johnson, the head of NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office, said at the SBAG meeting. “But don’t gloat around your Venus colleagues too much, because they’re certainly feeling down these days.”