The status of Russia’s human spaceflight program (part 1)by Bart Hendrickx

|

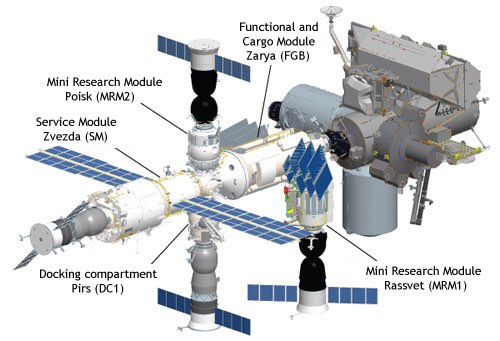

The current configuration of the Russian segment of the ISS (credit: RKK Energia) |

Downsizing the Russian ISS crew

When the Soyuz MS-04 spacecraft blasts off to the International Space Station from the Baikonur cosmodrome this spring, it will be carrying just two crew members (one Russian, one American) instead of the usual three. Taking the place of the second Russian cosmonaut will be additional cargo for the station’s Russian segment. The move results from a decision made last September to temporarily reduce the Russian ISS crew from three to two. Two reasons have been cited for the decision. One is that, due to shrinking space budgets, Russia can no longer afford to launch the amount of of Progress vehicles needed to maintain a three-person crew on a permanent basis. The second is that the current scientific workload on the ISS Russian segment does not justify the presence of three cosmonauts.

| The spacecraft that is supposed to take Russian cosmonauts to lunar orbit and back is years behind schedule and doesn’t have a launch pad yet. The heavy-lift rocket that should eventually enable Russian cosmonauts to land on the Moon hasn’t even left the drawing board. |

In recent years Russia launched an annual average of four Progress vehicles, but in April 2015 the Russian space agency decided to reduce that rate to three while revising its proposed budgets for the next decade. A solution to that problem is in the works, but quite some way off. In December 2015, RKK Energia, the country’s leading manufacturer of crewed space vehicles, was awarded a contract to start work on a new cargo vehicle that will need to fly only three times per year to deliver the same amount of supplies as four Progress ships. Capable of carrying 3.4 tons of cargo, about 800 kilograms more than Progress, it will be orbited by a more powerful version of the Soyuz rocket (Soyuz-2.1b), which made its inaugural flight in 2006. Provisionally called TGK PG (Transport Cargo Ship With Increased Payload Capacity), the vehicle will have a wider cargo section than Progress and will also carry more propellant both for its own engines and those of the station. The preliminary design phase was expected to be completed by the end of 2016, but the vehicle will not be ready to fly until after 2020, leaving Russia to rely on the venerable Progress for the remainder of this decade.

The second problem, the lack of scientific experiments, should be addressed much sooner. Late this year a big science module called the Multipurpose Laboratory Module (MLM) is set to be launched to the station. The module will significantly increase the workload of the Russian crew, so once it is in place, the Russians will expand their crew complement back to three. Russia had always intended to move to three-person crews only after the arrival of MLM, but the launch of the new module kept slipping endlessly. When the station had grown enough to expand the ISS crew to six in 2009, the Russians went along, but, with hindsight, that transition came much too soon for them. Now, with space budgets going down, the three-person crew is a luxury they seemingly can no longer afford. It is not clear if the Russian crew will be reduced back to two once MLM is declared operational. If not, that would be an indication that the low scientific workload has been a much more important factor in shrinking the crew size than the reduced Progress flight rate.

| In a rare case of public dissent with official Roscosmos policy, cosmonauts Oleg Skripochka and Aleksei Ovchinin expressed their reservations about the move shortly after returning from a stint aboard ISS last September, saying that science will exactly be the biggest victim of the crew reduction. |

A man who may well have been instrumental in pushing through the decision on the crew reduction is former cosmonaut Sergei Krikalyov, who in March 2016 was named head of the human spaceflight directorate of the Roscosmos State Corporation, the new entity that officially replaced the Russian Federal Space Agency on January 1, 2016. Krikalyov first spoke out on the need to reduce the crew only weeks after taking up the new post. He says the decision had been under consideration since 2015 and was made with the consensus of the cosmonauts, who are willing to spend more of their time on science if need be.

However, not everyone in the cosmonaut corps seems to think that is possible. In a rare case of public dissent with official Roscosmos policy, cosmonauts Oleg Skripochka and Aleksei Ovchinin expressed their reservations about the move shortly after returning from a stint aboard ISS last September, saying that science will exactly be the biggest victim of the crew reduction. Fyodor Yurchikhin, commander of the upcoming Soyuz MS-04 mission, has said he and his sole Russian crewmate will probably have to sacrifice much of their already limited spare time to keep up with the increased workload.

The downsizing of the Russian crew has forced ISS managers to significantly reshuffle the schedule of crews flying to the station this year. Two US astronauts (Mark Vande Hei and Scott Tingle), who were supposed to fly Soyuz as second flight engineer, will need extra training to perform the role of first flight engineer instead. As a result, their crews needed to be reassigned to missions later in the year. Two Russian rookie flight engineers, Nikolai Tikhonov and Igor Vagner, had to interrupt their training with no immediate prospects of a reassignment. Meanwhile, the vacant seats that will become available on Soyuz this fall and in the spring of 2018 may be occupied by American astronauts, increasing the “Western” crew complement from three to four. NASA will negotiate for these seats with Boeing, which has received them from RKK Energia as compensation for the settlement of a lawsuit involving the Sea Launch venture.

Krikalyov has said that the downsizing of the Russian crew will not affect plans to select a new batch of cosmonauts later this year. It has not yet been decided whether this will be another open selection drive like the latest recruitment in 2012. Only 304 people submitted valid applications at the time, a number that may well be a barometer of the level of interest in spaceflight among the Russian public these days. By contrast, more than 6,000 people responded to NASA’s call for astronauts in 2011–2012, the second largest number of applications the space agency ever received. Russia currently has 31 cosmonauts eligible for flight assignments, compared to 45 in the US.

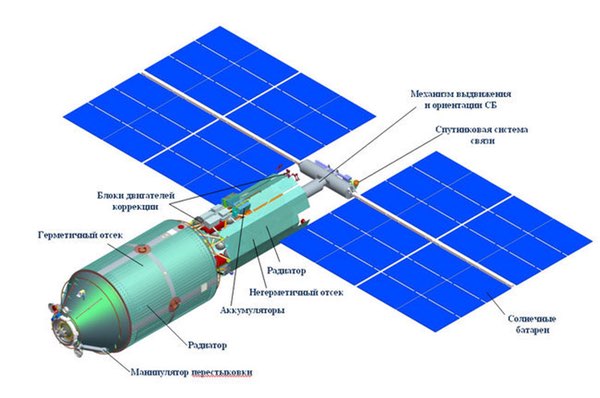

The Multipurpose Laboratory Module “Nauka” (credit: RKK Energia) |

Expanding the Russian segment

While the assembly of the space station’s US segment was completed with the addition of the Permanent Multipurpose Module in 2011, the construction of the Russian segment is only half-finished more than 18 years after the first element was orbited. Plagued by underfunding and mismanagement, the expansion plans have seen enough changes and delays over the years to fill several volumes. The ISS Russian segment has become a classic example of a dolgostroi, a term coined in the Soviet days for construction projects that drag on endlessly.

Up next should be the long-delayed 21-ton Multipurpose Laboratory Module. Also known as Nauka (pronounced “na-oo-ka”, meaning “science”), it will significantly expand the scientific potential of the Russian segment by providing new laboratory space and offering the possibility to expose experiments to the vacuum of space through an airlock.

So far the Russian segment has lacked a dedicated science module. The Zarya (“dawn”) “Functional Cargo Block” (financed by the US, but built in Russia) launched in 1998 is mainly used for storage, the Zvezda (“star”) “Service Module” orbited in 2000 primarily serves as the Russian segment’s functional center and living quarters, and the Pirs (“pier”) module docked to the Zvezda nadir port in 2001 is an EVA airlock with a Soyuz/Progress docking port. Two new small modules called Poisk (“quest”) and Rassvet (“dawn”) linked up with the Zvezda zenith and Zarya nadir ports in 2009 and 2010. Originally conceived as small research modules, they were redesigned for new tasks, leaving little room for scientific experiments. Poisk was turned into a near-copy of the Pirs airlock and opened up a new Soyuz docking port on the Zvezda zenith location. Rassvet is essentially an extension that was needed to give approaching Soyuz and Progress vehicles enough clearance to dock with Zarya after the installation of the Permanent Multipurpose Module on the adjacent nadir port of the American Unity node.

| MLM’s road to space has been unusually arduous. Construction of the vehicle began at the Khrunichev factory in Moscow back in 1995 with the aim of having a spare for Zarya in case the launch of that critical module failed. |

Strictly speaking, not even MLM is a specialized science module like NASA’s Destiny, ESA’s Columbus, and JAXA’s Kibo. Instead, it will perform an amalgam of functions once intended to be scattered over various modules. In addition to its science payload, it will have a third sleeping bunk for the Russian crew (Zvezda having only two), an additional toilet, and carry important new life support systems, such as an oxygen regeneration system and an installation to turn urine into potable water. Having pioneered that water recycling technology on the Mir space station back in the 1990s, the Russians have for some reason not yet introduced it on ISS. With water supply becoming a potential problem after the reduction of Progress flights, they intend to install the recycling device on Rassvet if the MLM suffers more delays. Mounted on the outside of the MLM will be a European Robotic Arm (ERA) developed by Dutch Space that is capable of “walking” over the Russian segment with the help of special fixture points that provide both electrical and mechanical interfaces. In addition to all this, MLM’s engines will be used for roll control of the station.

MLM’s road to space has been unusually arduous. Construction of the vehicle began at the Khrunichev factory in Moscow back in 1995 with the aim of having a spare for Zarya in case the launch of that critical module failed. After Zarya successfully reached orbit in 1998, the Russians floated a multitude of ideas to adapt its backup vehicle for other tasks. The idea to outfit it as a laboratory module originated in 2003, but a government contract to adapt it for its new role was not signed until March 2008. After almost five years of work, the module was shipped from the Khrunichev factory to prime contractor RKK Energia in December 2012 for final outfitting and testing. In late 2013, with just months left before launch, some of the module’s propellant lines were found to be contaminated, after which it had to be shipped back to Khrunichev for repair work that has now been going on for three years.

The whole MLM saga must be extremely embarassing to the Russians, the more so because it has left a major non-Russian component (the ERA arm) in storage for at least a decade. Only scant information on the latest troubleshooting efforts is leaking out from behind the walls of Khrunichev, making it difficult to assess what the current status of the vehicle is. Even a 900-page book recently published by RKK Energia about its activities in 2011–2015 devotes just a single line to MLM’s latest woes. It is a story that begs for a solid piece of investigative journalism, but judging by the lack of reportage even in the Russian aerospace press, reporters have been either unwilling or unable to figure out what exactly is causing the extended delays.

Anatoly Zak, a US-based observer of the Russian space program, writes on his respected RussianSpaceWeb.com website that the latest delays are of a political nature, caused by worsening relations between the leadership of the space industry and military quality control officers in charge of certifying space industry manufacturing operations. Some critics have argued the module has already outlived its usefulness before leaving the ground and should be sent to a museum rather than to the ISS.

Officially, the MLM launch is still targeted for December 2017, but unofficial reports suggest it will likely slip to the first half of 2018 or even later, further delaying the return to a three-person Russian crew complement. Whenever MLM is finally ready to go, its launch will set off a flurry of activity on the Russian segment. That work will actually begin even before MLM arrives, because the aging Pirs airlock will first have to be detached from the station with the help of a Progress resupply ship to free up the Zvezda nadir port for MLM. Four components for MLM—the airlock, a radiator panel, a back-up elbow joint for the ERA, and a portable work platform—were already delivered to the ISS on the exterior of the Rassvet module in 2010 and will be transferred to MLM shortly after its arrival.

At least eleven spacewalks will be needed to prepare the station for the undocking of Pirs and the docking and integration of MLM. In that respect, the repeated delays of the MLM launch may be a blessing because Russian cosmonauts have been unable for a while to perform underwater simulations of EVAs. In December 2014, the hydrolab at Star City near Moscow was drained for maintenance work that was supposed to have taken а year, but the facility is not expected to resume operations until this month. Star City chief Yuri Lonchakov largely attributed the delays to the sanctions imposed on Russia, which have made it impossible to import new components for the facility from the West.

| The repeated delays of the MLM launch may be a blessing because Russian cosmonauts have been unable for a while to perform underwater simulations of EVAs. |

The docking of MLM will set the stage for the launch later in 2018 of the Node Module (Russian acronym UM), also known as Prichal (“berth”). Looking very similar to the spherical docking adapter of the Mir core module, it sports six docking ports—two axial and four lateral—that will make it possible to further expand the Russian segment. The flight model was completed in 2014 and has since been sitting in storage at RKK Energia pending the launch of MLM. Weighing 4.7 tons, the module will be launched by a Soyuz rocket and delivered to the ISS in the same fashion as the Pirs and Poisk modules, using a modified Progress service module as a space tug. It will dock with the nadir port of MLM and act as a docking port for transport ships and future modules.

The Node Module “Prichal” (credit: RKK Energia) |

Although Prichal can receive four more modules, Roscosmos right now has firm plans for only one more, called the Science Power Module (Russian acronym NEM). Weighing more than 20 tons, it will consist of a pressurized and unpressurized section. The pressurized section, which will have about the same volume as Zvezda, will offer additional room for scientific experiments, housing standard payload racks that can easily be replaced. Mounted on the outside will be a mobile robotic system that can relieve cosmonauts of numerous EVA duties, much like the Canadian-built Dextre robot on the US segment.

The Science Power Module (credit: RKK Energia) |

The unpressurized section will be fitted with two big solar arrays that should end Russia’s reliance on power provided by the huge US solar arrays. Right now, the only power generated by the Russian segment comes from the much-degraded solar panels of the 16-year old Zvezda module. The solar arrays of Zarya were retracted in 2007 to make way for a radiator extending from the station’s Integrated Truss Structure. NEM’s solar arrays, along with those of NEM, will make the Russian segment fully self-sufficient in terms of power supply.

NEM has had a beleaguered history not unlike that of MLM. A power module was part of the original plans for the Russian segment formulated in the 1990s, but it has undergone numerous mutations over the years. Testifying to the long delays in the NEM project, the Rassvet module currently docked to ISS was constructed on the basis of a dynamic test model built for an earlier iteration of NEM. Once scheduled for deployment from the space shuttle, NEM was scrapped from the shuttle payload manifest in 2005 when NASA decided to cut back the remaining number of shuttle missions. The agency agreed to compensate for that by supplying US power to the Russian segment from 2007 to 2015 under a barter arrangement.

RKK Energia was awarded a new contract to the build the NEM in 2012 with the goal of launching it in 2015 or 2016. However, four years later there are no signs that the flight hardware is anywhere near ready, and the launch is now expected no earlier than 2019. Some press reports have suggested the project was stalled by bureaucratic infighting between RKK Energia, Roscosmos, and its affiliated TsNIImash research institute, mainly over modifications that need to be made to the Proton rocket that will launch NEM. For reasons that are not entirely clear, RKK Energia outsourced construction of the pressurized module to the Progress Rocket Space Center in Samara, which has until now specialized in building the Soyuz launch vehicle and reconnaissance and remote sensing satellites. It is the first time a Russian human-rated spacecraft is built by another organization than RKK Energia and Khrunichev. A static test model of the pressurized module was delivered to RKK Energia last October. It is not clear how far the production of the flight model has progressed. After launch, NEM will first dock to the nadir port of the Node Module before being relocated to one of the axial ports with a small manipulator arm.

One more module that could eventually join the Russian segment is an inflatable module similar to the ones being developed by Bigelow Aerospace in the US. RKK Energia has been doing research on such modules (which it refers to as “transformable modules”) on its own initiative since 2011. Drawings released by the company show an inflatable structure attached to a Progress service module that can be launched by a Soyuz rocket. The work has so far not been funded by Roscosmos and does not seem to be fully supported by the TsNIImash research institute, which concluded last year that inflatable modules are twice as expensive to develop as rigid modules of equal size and can only become cost effective if they are mass produced. That hasn’t stopped RKK Energia from continuing its research, with company genera director Vladimir Solntsev declaring last November that an inflatable module could be ready to fly to ISS in 2021. Yet another vehicle that the company worked on for many years, a free-flying module called OKA-T that would periodically dock with the ISS for servicing, does seem to have been definitively abandoned as a result of recent budget cuts.

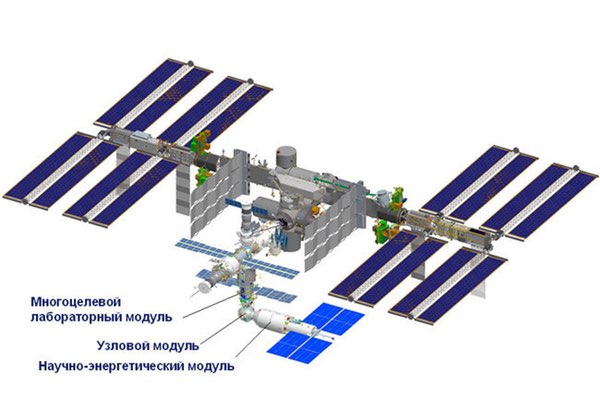

The final configuration of the ISS Russian segment (credit: RKK Energia) |

A new Russian space station

Soon after the Mir space station was deorbited in 2001, Russian space officials began making public statements about the intention to create a new all-Russian space station in the post-ISS era. Early plans focused on what they called a “high-latitude space station” that would fly in a higher inclination than ISS (70° vs. 51.6°) to improve remote sensing coverage of Russian territory. Other than that, the station would be used for the same type of scientific experiments conducted on ISS and also to test technology for future missions to the Moon and Mars. It would be a much smaller station than ISS that might not even be permanently crewed.

| As a result of deteoriorating relations with the West, the Russian space agency weighed the option in late 2014 and early 2015 of not sending the new modules to ISS at all and instead launching them into a new orbit with a higher inclination (64.8°), a return to the idea of a “high-latitude” station. |

Critics argued that it made little sense to place so much emphasis on Earth observation, a task that can better be entrusted to cheaper robotic satellites. Indeed, the remote sensing objective gradually disappeared from official statements on the follow-on station, but not only because of the above argument. As the launch of new add-on modules for the Russian segment kept slipping closer and closer to the expected end of ISS operations, the idea took shape to detach those elements from the ISS to form a new independent Russian space station. That, of course, ruled out the use of a significantly higher inclination.

There are strong indications that changes made to the planned configuration of the ISS Russian segment in 2006 were largely driven by this objective. The clearest evidence for this is the conception of the Node Module, which has more docking ports than are planned to be used during ISS operations. The Node Module is reportedly certified to stay in space for as long as 30 years and could become the permanent hub of the station, with new elements coming and going as necessary.

As a result of deteoriorating relations with the West, the Russian space agency weighed the option in late 2014 and early 2015 of not sending the new modules to ISS at all and instead launching them into a new orbit with a higher inclination (64.8°), a return to the idea of a “high-latitude” station. However, with serious budget cuts looming, the agency decided in February 2015 to extend its participation in ISS until 2024, although it kept open the option of undocking the newest elements to build a Russian space station after the retirement of ISS. That possibility is also specifically mentioned in the Federal Space Program (FSP) for the period 2016–2025, a crucial policy document approved in March 2016 that outlines objectives and planned funding levels for all Russian government-funded civilian space activities over the next decade.

Russian Orbital Station with detached elements of the ISS Russian segment plus an inflatable module and airlock module (credit: RKK Energia) |

The latest drawings of what is now called the Russian Orbital Station (ROS) were shown by RKK Energia head Vladimir Solntsev at the International Astronautical Congress in Guadalajara, Mexico, last September. They show a station consisting of the Node Module, the Multipurpose Module, and the Science Power Module, as well as an airlock module and an inflatable module, two elements that are currently not funded. Whether it will still make sense to include the Multipurpose Module is an open question. Having languished at the Khrunichev factory for over 20 years, the module has a guaranteed on-orbit lifetime of only seven years (until 2024). However, as Solntsev pointed out early last year, that period may well be prolonged. After all, its sister ship Zarya has already been exposed to the much harsher conditions of space for more than 18 years without suffering any significant problems.

Meanwhile, there are indications that Russia may well decide to stay aboard the ISS even if it remains in orbit longer than 2024. Speaking to the Rossiyskaya gazeta newspaper last December, Roscosmos deputy general director Yuri Vlasov said he expects Russia to keep all its elements attached to the station if its life is extended to 2028. He essentially described this as a goodwill gesture from the Russian side inspired by both technical and political motives: “Although we have the means to launch new modules that will allow us to detach the Russian segment and work independently, it is difficult to imagine how the ISS could be operated without our piloted ships and cargo ships. [A decision to stay on board ISS should be seen as] more of a political move: space is a bridge between countries irrespective of what happens on Earth. It unites people and makes us realize that we are one big family.”

Another Russian official, Dmitri Rogozin, has used the US dependence on the Russian segment to utter more provocative statements. In his capacity as Deputy Prime Minister for the defense and space industry, Rogozin is the highest government official in charge of the Russian space program. One of the first Russian citizens to be blacklisted by the US following the Crimea crisis in 2014, he is most notorious for having tweeted that US astronauts may one day find themselves flying to the ISS on a trampoline. In a television interview early last year he poured more oil on the fire by reminding the US of its precarious position in the ISS program: “If we want, we can undock our segment from the ISS tomorrow and continue to operate it in orbit. The Americans don’t have that possibility. They are totally dependent on us. Without us they are nothing.”

What both Vlasov and Rogozin are alluding to is the fact that the US is totally reliant on Russia for crew transportation and re-boost capability. Although the US commercial crew vehicles should soon put an end to the crew transportation problem, the US segment will remain devoid of propulsion systems capable of raising the station’s orbit. Such burns are performed either with the engines of the Zvezda Service Module or attached Progress cargo ships. Progress is also the only vehicle capable of refueling the station. Unless the US develops a dedicated vehicle for that purpose, Russian propulsion systems will also be needed to eventually deorbit the ISS. As reported last year, the new cargo ship currently under development to replace Progress is being designed to handle that task. Any decisions on the future of ISS and continued Russian participation in the station will have to take these factors into account.

| Whatever goal a new Russian space station might serve, Russian space officials realize that maintaining a human presence in Earth orbit (whether that be on the ISS or a Russian station) and sending people into deep space at the same time is something the nation can hardly afford. |

With its 45-year expertise in operating space stations, there is no doubt that Russia is perfectly capable of establishing another space laboratory in Earth orbit. The only question is what benefit such a station would have, apart from upholding the nation’s prestige in human spaceflight. Some Russian space analysts have expressed skepticism about the need for another Earth-orbiting space station. As one of them, Yuri Karash, put it several years ago: “Why should we launch another space station? We could of course use one mission to grow peas, another to grow garden pansies and subsequent ones to fly quails, newts and ladybirds… However, the fact of the matter is that all goals that needed to be accomplished in Earth orbit have already been achieved on earlier stations. Earth orbit is not a goal in itself but only a stepping stone to deep space. In that respect it has fully exhausted itself.”

At present, NASA intends to leave piloted operations in Earth orbit in the hands of the private sector, assuming that is deemed to be a commercially viable enterprise. So far, there are few signs that Russian private companies are interested in entering the manned spaceflight business. A Moscow-based consortium called “Space Technologies” recently announced plans for a space station dubbed Mir-2 that would be assembled in orbit between 2027 and 2032. Shaped like a wheel, it would allow its passengers to live in conditions of artificial gravity. However, the sources of financing for the project are not clear and few in the Russian space community seem to be taking the initiative seriously.

Whatever goal a new Russian space station might serve, Russian space officials realize that maintaining a human presence in Earth orbit (whether that be on the ISS or a Russian station) and sending people into deep space at the same time is something the nation can hardly afford. Roscosmos’ manned spaceflight chief Sergei Krikalyov summed up the dilemma in a recent interview: “Does it make sense to detach the Russian segment or should we stay on ISS? Will it be a periodically visited or a permanently manned station? The need to have humans in low Earth orbit will, of course, remain, but we are still discussing in which form this should be. The main disadvantage of keeping ISS operational in the future is that it will divert resources from lunar exploration.”

An ultimate decision on a Russian space station may at least partially depend on the scientific return from experiments conducted on the ISS Russian segment. During a meeting with space officials last November, President Vladimir Putin stressed that the scientific output of the Russian segment should be higher considering the amount of money invested in ISS. The latest word on the fate of the follow-on station came this January from Dmitri Rogozin, who said a final decision, based on both political and technical factors, may be made next spring.