Review: The Final Missionby Jeff Foust

|

| LC-39A, Kennedy Space Center director Bob Cabana said in a pre-launch briefing, would have “rusted away in the salt air” without a new user for the pad. |

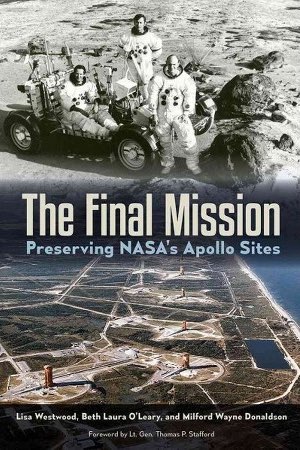

LC-39A is hardly the only piece of space history whose future is in jeopardy, or has already been lost, over the decades. Preserving that historical record, on Earth and on the Moon, is the subject of The Final Mission, a book by a group of archeologists who specialize in space history.

Part of the book recounts the history of the American space program, in particular the heritage created by the Apollo program. (The book is subtitled Preserving NASA’s Apollo Sites, so the historical record of the Soviet/Russian and other national program is beyond its scope.) This includes not just launch sites, like Launch Complex 39, but also testing and other facilities, involved in NASA and predecessors like NACA, and even sites that the Apollo astronauts visited in geology field trips to train for the lunar landings. For those already familiar with the history of the space program, much of this can feel a little repetitive.

The second part of the book examines the challenges of protecting those historical sites. On Earth, the problem is the difficulty getting a site just a few decades old recognized as “historic”: such sites typically have to be at least 50 years old before being eligible to be a National Historic Landmark under current law. The law does include exceptions for particularly historic sites younger than that, but that can clash with concerns from agencies and companies that the designation might restrict changes to such facilities that are still in use today.

On the Moon, the issue is one of jurisdiction. Under the Outer Space Treaty, the United States cannot claim the landing sites of the Apollo missions or other spacecraft as US territory, and thus they cannot be protected by the same laws used for historic sites within the US. Two House members proposed legislation in 2013 that would designate the Apollo sites as a national park, but it failed to win passage in part because of legal concerns. The authors suggest that the US take the lead in international discussions on ways to protect historic sites beyond Earth, perhaps based on the model used in Antarctica.

| The authors suggest that the US take the lead in international discussions on ways to protect historic sites beyond Earth, perhaps based on the model used in Antarctica. |

Such a solution will likely take years to develop, given the slow pace of international negotiations and the low priority preserving space heritage has compared to more pressing concerns. NASA has developed guidelines for how its lunar sites should be preserved, developed in anticipation of Google Lunar X PRIZE teams potentially landing and roving in their vicinity, but those teams, or other companies or government agencies, are not bound to abide by them. So far, though, teams have shown a willingness to follow those recommendations.

The Final Mission offers an interesting perspective on the challenges of preserving artifacts from an effort that is still fairly young, and one that is—or, at least in its early years, was—fast moving. They note in the end of the book that no one would doubt that Launch Complex 39 would be considered a historic site. But that site today is different from how it existed when it hosted the launches that made it historic. Is it better to modify those sites to keep them active, or let them lie fallow in their previous condition, and rust away in the salt air?