Loss of faith: Gordon Cooper’s post-NASA storiesby James Oberg

|

| Cooper’s “space treasure map” and “secret military sensor” story is not unusual compared with other late-in-life tales that are easily dismissed as imaginary. |

But the problem in establishing the authenticity of these narratives raises uncomfortable questions over their impact on Cooper’s place in history. His undeniable skill and courage in the early Space Race should be enough to guarantee his honor and fame. All too often, heroes don’t age well, so compassionate historians avert their eyes from the twilight years of such luminaries, as they have with Cooper and his sad fall from grace within the astronaut corps.

The dilemma facing historians is how to react when subsequent writers and publicists bring up the activities and opinions of this declining phase of a hero’s life and seek to validate them based on the person’s original heroism, decades earlier. In such cases, full candor is the distasteful response demanded of history, lest an unwary audience assume the hero’s intellect remained at its peak performance forever.

The material in the following article, then, is information that spaceflight workers and enthusiasts would rather not be widely disseminated, although none of it was actively kept secret. The only justification for reviewing it now is that for whatever reason, a television production company and channel, spearheaded by enthusiastic individuals who could well be sincere, have dredged up late-in-life stories from Cooper and deliberately relied on the fame he deservedly earned in his prime rather than honestly portray his mental state much later, when he made these and other similar claims.

Cooper’s “space treasure map” and “secret military sensor” story is not unusual compared with other late-in-life tales that are easily dismissed as imaginary. He told “I was there” yarns about spaceflight that clearly never happened, such as his account of how his Gemini 5 capsule was peppered by loud meteorite impacts in flight that left deep gouges in the skin (nobody at NASA could see any damage on return to Earth, and the capsule is on public display in Houston.) He recounts in detail a meeting he had with a NASA official to relay a drawing of a shuttle design flaw that a friend of his gave him after making it under the influence of aliens, and he claimed the flaw was found exactly as described and fixed—except there’s no record of such a flaw or such a fix.

The most relevant such story involved a “secret camera” he carried (and it was real) on Gemini 5 for the Defense Department, which took photos so sharp he could read auto license plates when he saw the prints, which he claimed had been sent away to top secret archives. But the photos were never classified, were on file in Houston, and show details at best as big as city blocks: moving at 7,600 meters in orbit, a camera with a 1/50-second exposure is going to suffer a lot of image smear.

One particular note in the NASA archives relates directly to the “Cooper’s Treasure” program. The catalog for the NASA archives lamented that the Gemini 5 pictures were of limited utility because there was little, if any, crew documentation of where the photos were taken. “The astronaut log is sketchy and difficult to use for any data of value,” it said. Yet we are now being told that two years before doing such a poor job at documenting the space photos he was taking on Gemini 5, he had done a much better job on Mercury 9—complete with latitude and longitude readings he had apparently forgotten how to determine on the Gemini flight. If he couldn’t do it on Gemini with better windows, better navigation, longer time, repeated passes over same areas, and a copilot to take real-time notes, it’s a good bet he never would have been able to do it on Mercury.

| Investors, both corporate, government, and individuals, gave companies endorsed or organized by Cooper over $2 million during the 1980s and 1990s, and everybody lost every dime. |

Other events from the dark final years of Cooper’s life give additional insights for properly evaluating the treasure map story. He apparently told some very convincing tales about how he had discovered a map of sunken treasure, based on secret equipment on his first space flight in 1963, and only needed time and a little more money to achieve success. Darrell Miklos was one of those people he told the story to, and appears to totally believe Cooper’s account based on his heroic reputation. “I believed Gordon 100 percent,” he famously told Parade magazine, “I didn’t need proof…”

A long history of questionable ventures

But perhaps space enthusiasts who think that Cooper’s NASA career is adequate grounds to believe all the stories he tells might be advised to read the feature article in the Wall Street Journal for November 7, 1997. The story by staff reporters Ellen Joan Pollack and Carlos Tejada is titled “Down to Earth: An Astronaut’s Fame Draws Desperate Cities into Risky Investments”, with the subtitle “Gordon Cooper Was a Hero In Space but Has Trouble Making His Business Fly.” It’s behind the newspaper’s paywall but summary of it follows.

Investors, both corporate, government, and individuals, gave companies endorsed or organized by Cooper over $2 million during the 1980s and 1990s, and everybody lost every dime. Cooper said it was all their own fault.

Cooper completely trusted his partners in these companies, and he also trusted his own engineering and business instincts. According to Al Bubis, a partner in two of the failed companies, “He doesn’t believe anybody’s going to say things that are not true. You have to believe, if you go up into space in a pillbox.”

For Cooper’s first commercial experience after leaving NASA in 1970, he was hired as a consultant by Dalton Smith, who used Cooper’s name to clinch a number of deals. Cooper was paid not in cash but with a small airplane, which he spent a lot of his own time, effort, and money refurbishing.

Then he was told the aircraft had not even been Smith’s (who was also convicted of fraud for some other business activities), and it was repossessed, leaving Cooper in the hole for his work.

Smith then asked Cooper to take part in a second consulting project with him. Incredibly, Cooper, who thought of Smith as “a nice guy,” accepted.

The deal would sell millions of dollars of helicopter parts to El Salvador. Cooper was sent to El Salvador to supervise the unloading (he had been present in the US when the ship was loaded), but began to feel “queasy,” quit, and left the country.

When the ship arrived, it was loaded with scrap metal, and the valuable parts which had been paid for, were missing. Cooper just couldn’t figure out where the real merchandise had disappeared to, and Smith died before explaining it to him.

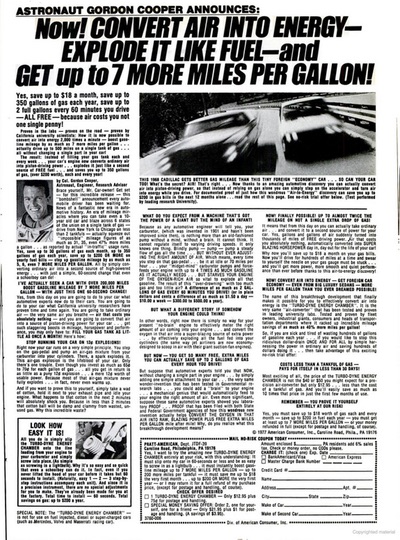

A 1978 ad featured Gordon Cooper selling a product that claimed to enhance gas mileage. |

Next, Cooper was a spokesman for “American Consumer Incorporated,” and appeared in newspaper ads extolling a gasoline-saving device for automobiles. “Astronaut Gordon Cooper Announces: Now! Convert Air into Energy – Explode it Like Fuel,” said the ads, next to a photograph of Cooper in a spacesuit.

The Federal Trade Commission concluded the device was a scam and ordered Cooper to stop endorsing it, and the company collapsed.

| Cooper completely trusted his partners in these companies, and he also trusted his own engineering and business instincts. |

In 1975, Cooper went to work for Walt Disney Productions, and developed a number of ideas on theme park rides, waste disposal, and other technical issues. But when the company decided that not a single idea was worth implementing, Cooper left in frustration.

Next was a plan to develop an ethanol-powered automobile engine, where he first met Al Bubis. The company, Vis-Tec Inc., needed capitalization, so Cooper traveled around telling spaceflight stories to charm investors.

One investor recalled a dinner where Cooper described “electromagnetic concepts,” and told the WSJ reporters, “His theories, which I would have difficulty articulating at this point, seemed to be an intelligent approach.” He went in for $100,000. Within a year it was all gone and Vis-Tec filed for bankruptcy.

Next up was an aviation business idea, where in the early 1980s Cooper flew methanol-powered small airplanes around the country. With his friend Al Bubis, he founded XL Inc. to commercialize the idea, which he claimed was based on his own experience in NASA where he once had to fly a jet back to Houston using methanol.

Aside from Cooper’s version of the story, there is no documentation it ever happened, and an engineer that XL hired to duplicate the performance was unable to get the same results that Cooper remembered.

Investors were eager to hear Cooper’s astronaut stories but less willing to part with money (the experiences of investors in Cooper’s earlier ventures had apparently become widely known), so eventually Bubis and other members of the XL board of directors decided to divert their efforts into projects more likely to make a profit. Cooper felt betrayed and quit in anger.

In 1987, Cooper founded the Galaxy Group, Inc., with the goal of commercially upgrading the engines of small airplanes to more efficient designs. This time he turned to fellow pilots for money, and raised close to a million dollars from private investors, many of them retired aviation workers (he also put in $300,000 of his own money.)

His vice president at Galaxy was a California businessman named G. Pendleton Parrish, who came from an investment firm that had won a $300,000 contract from the state of Louisiana for several state development projects. None was ever built, and a state audit found that much of the money had been spent flying officials back and forth from California.

After another of Parrish’s business deals was aborted, a friend of Cooper’s tried to warn him not to trust Parrish, but Cooper refused to listen. “Gordon even got a little bit mad at me and I just sort of backed off and said, ‘It’s your company,’” the man told the WSJ reporters.

Through Parrish, Cooper hired Michael Franzese, stepson of a crime-family boss who himself had recently been convicted on federal racketeering and tax-conspiracy charges. He spent six months supposedly looking for investors while running up $29,000 on a company credit card before being arrested on an unrelated parole charge and sent back to prison.

Cooper’s next plan for financing was to find a desperate small community in need of jobs that his airplane plans could provide. Over a period of several years he negotiated with five towns, while “regaling local politicians with tales from space” and handing out autographed photographs.

His negotiations with Edinburg, Texas, began in 1991. “Here was this hero, this national hero,” recalled Rudy De La Vina, then the mayor. “We believed in Colonel Cooper,” recalled Alejo Salinas, Jr., then a city commissioner.

| “There was a glimmer of hope for development,” Salinas remembered. Then, he continued, “they took our glimmer, and they took our money.” |

The town decided to loan Cooper’s company $1.3 million, a major chunk of its annual budget, although other local entities were suspicious. The independent Council for South Texas Economic Progress warned that there were “many unanswered questions and huge gaps in Galaxy’s financial statements and bonafides,” but when compared with the reputation of an astronaut hero, these views were ignored.

In 1992, Cooper led the town’s Fiesta Hidalgo parade to celebrate the deal. “There was a glimmer of hope for development,” Salinas remembered. Then, he continued, “they took our glimmer, and they took our money.” Added Charlie Espinoza, the one commissioner out of five who had voted against the deal, “It was too good to be true.”

As Cooper’s company spent the money, it failed to make progress on the project. At one point, to get some operating funds, it cashed in a $325,000 bond which it had listed as collateral for the town’s loan. Cooper says the town gave permission; two Edinburg officials say they never were asked.

Cooper offered to replace the collateral with an airplane, and three town officials flew to California to look at it rather than just take Cooper’s word for it. Rather than show them the plane, Cooper drove them past Hollywood homes, the Santa Monica beaches, and offered to introduce them to John Travolta, before putting them back on their flight without ever showing them the plane they had come to see (Cooper later claimed they weren’t interested in the plane and just wanted to go sightseeing.)

Soon the money was gone and the project collapsed, and the town never got any collateral for the defaulted loan.

By then Cooper was already negotiating with other towns. He went to Macon, Georgia, but his demand to take over existing facilities was rejected. He went to his own hometown, Shawnee, Oklahoma, and promised them 2,000 new jobs within four years, if the city would finance the entire project. His hometown said no.

Then he tried Edwards Air Force Base, California, where aerospace cutbacks had hurt the local economy but where there were many retired pilots who might be expected to like the idea or, at least, like anything that a famous astronaut was proposing. The town of Lancaster decided to give Cooper’s company $300,000 to set up shop; Cooper, meanwhile, also liquidated most of his own holdings, including land in Colorado given to him by his mother, to provide more funds.

Arnie Rodio, who was mayor of Lancaster at the time, told WSJ reporters they hadn’t realized that Galaxy “was operating on a shoestring.” When the project failed to materialize, the town sued Cooper’s company and won a court judgment, which as of the time of the article [1997] hadn’t been paid.

Rodio lost his reelection bid when the Cooper project became a campaign issue in the next town election.

According to court documents reviewed by the Wall Street Journal, Cooper denied any wrongdoing and blamed all of the failures on each of the towns. He also criticized Edinburg for breaking a promise not to sue him for default.

“Certainly I feel bad that we didn’t have a successfully going project down there,” he told a reporter, “but there were valid reasons why we didn’t.”

During the interview for the Wall Street Journal in 1997, Cooper described how it would only take $2 million to get his company back on its feet and making a profit. He believed it was just a matter of time, despite two failed attempts to take the company public and raise funds through stock sales.

| The dramatic aerial maneuvers that Cooper describes having personally witnessed, she writes, never happened, and never could have happened. |

According to the WSJ, Cooper had his eye on a project to build logging helicopters for Fiji, and he had been in touch with an inventor of a new piston engine for small airplanes that is “so simple, you can’t believe it will work.” Investors from Mexico and Taiwan were looking him over, he told reporters. “We don’t have a check in hand,” he admitted in 1997, “but we’re looking very optimistic.”

The flying saucer that didn’t

Another get-rich project Cooper championed in his autobiography Leap of Faith was Wendell Welling’s “flying saucer engine” the Utah rancher had invented and tested on his ranch in Utah. Cooper describes [p. 207] his visit there after Welling had died and the impression the device made on him.

I sat at the control station about ten feet away. The sole ‘flight control’ was an airplane-type stick… The only noise in the room was the slight whir of the generator. I applied gently backward pressure on the stick, and the saucer jumped off the test stand, soundlessly, and rose into the air effortlessly to ten feet or so. I was amazed by the ease with which the bird took flight. Up and down it went as I moved the stick forward and back… I was extremely impressed with the saucer’s lift capabilities. With very little power – the fan wasn’t even powerful enough to move air effectively through a large room on a hot day – this thing flat-out FLEW.

I flew the saucer for about ten minutes, and the experience really opened my eyes to what a vehicle of this configuration would do, specifically, the tremendous lift that could be developed from the saucer shape. BOY, I thought, WE’VE BEEN GOING THE WRONG WAY ALL THESE YEARS WITH WINGED AIRCRAFT…. [p. 266] I’ve never forgotten what I saw … in Wendell Welling’s barn.

The story was the sensation of the UFO internet after the book came out, and its implications were obvious. Wrote one blogger, “It’s too bad some dot-com millionaire in the States isn't interested in this stuff. Apparently there's a barn full of made-in-the-USA, functioning prototype flying saucers just sitting there waiting to take someone and us, to the next level. Steve Ballmer or those Google guys could probably finance the effort out of couch change.” It would just need somebody else’s money.

Curious to track down what had become of this invention, with a few lucky breaks I tracked down Welling’s daughter Gloria. She was amused by his book’s description of the demonstration flight, which she attended, because according to her, it never happened. He was there, all right (and she didn’t even think to take photos, sadly) but the model was covered with dust and had no power connection and hadn’t flown in years. And it didn’t for Cooper.

“Gordon didn't hold any controls and fly a prototype around a warehouse for 10 min,” she emailed me in 2015. The dramatic aerial maneuvers that Cooper describes having personally witnessed, she writes, never happened, and never could have happened. One small motor was turned on and vibrated on the test stand; that is all. “Bless Gordon’s heart,” she had written, “he didn’t write down his memories of northern Utah quite soon enough, and got a few facts wrong. but he was excited and meant well, I think… So no, the plans were never sold to foreign countries, and no there’s no gold mine of saucers in some northern Utah shed.”

These sad stories may provide adequate context for assessing the accuracy of the aerospace tales Cooper was telling in those years, and perhaps insights into speculating on his motivation—a subject beyond the scope of this article.