Reviews: The (counter)cultural influences on NASA in the Space Ageby Jeff Foust

|

| Maher decided against a relatively narrow history in favor of a broader one, examining how NASA affected, and was affected by, the broader political forces at work in the 1960s and 1970s. |

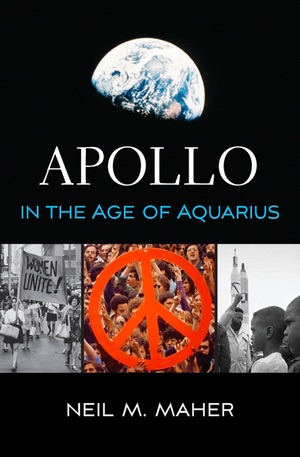

That anecdote—representative of the clash of cultures of the era—opens Apollo in the Age of Aquarius, a book by Neil Maher that attempts to put the space race of the 1960s, and its aftermath in the 1970s, into a broader perspective. That race to the Moon took place during one of the greatest eras of upheaval in America since the Civil War, and one that influenced NASA in ways often overlooked by other historians, he argues.

In the book’s introduction, Maher, a professor of history at the New Jersey Institute of Technology and Rutgers University, said he originally planned to write a very different book: an “environmental history” of the original space race that examined the links between nature and space technology, from the environmental control systems developed for spacecraft to the portrayal of space as “the ultimate wilderness.” As he did the research for the book, though, he decided against such a relatively narrow history in favor of a broader one, examining how NASA affected, and was affected by, the broader political forces at work in the 1960s and 1970s, from civil rights to Vietnam to women’s’ rights.

The book explores those issues, which also include environmentalism and both the counterculture and new conservative movements of the era. Some of those topics have been the subjects of entire books, in particular civil rights (see “Review: We Could Not Fail”, The Space Review, June 8, 2015) and women’s rights through the selection of the first female astronauts (see “Review: Integrating Women into the Astronaut Corps”, The Space Review, December 19, 2011). Others, like NASA’s largely behind-the-scenes role supporting development of technologies for potential use in the Vietnam War, are far less known.

| But as NASA achieved that goal of men on the Moon, it demonstrated it could not achieve escape velocity from societal forces, which pulled at the agency’s budget and ultimately its mission. |

NASA, hailed for landing men on the Moon as the 1960s came to a close, was also facing criticism from many quarters. Civil rights advocates not only considered such programs a waste of money, they argued NASA itself wasn’t doing enough to hire people of color. Women’s right advocates made similar complaints about NASA’s workforce. NASA also faced anti-war protests for even its study of potential ways—largely never implemented—that space-related technologies could aid the war in Vietnam (one proposal would have placed a giant Mylar balloon in geosynchronous orbit to reflect sunlight over parts of Vietnam at night, depriving the Viet Cong from moving under the cover of darkness.)

NASA’s original mission, of course, was not racial or gender integration or supporting a war in Vietnam. It was born of broader geopolitical conflict between the US and USSR, and given the goal of landing a man on the Moon to demonstrate US technological superiority. But as it achieved that goal, it demonstrated it could not achieve escape velocity from societal forces, which pulled at the agency’s budget and ultimately its mission: NASA, to remain relevant in the post-Apollo era, looked inward, supporting Earth science missions and spinoff applications of space technology, such as the energy crises of the 1970s. (It’s clear from some of the discussions in the book where research from Maher’s original plan for an environmental history of the space race survived.)

Maher’s analysis sometimes seems to push NASA’s influence a bit too far. The agency gets blamed for contributing to suburban sprawl by developing its space centers on campuses on the outskirts of cities, like Johnson Space Center in Houston or Goddard Space Flight Center outside Washington, DC. These followed the trend for corporate centers located in suburbs, like GM’s Technical Center outside Detroit, but also had practical reasons as well. These centers were more than just office complexes, but also charged with developing and testing space hardware, including, in the case of Marshall Space Flight Center on the edge of Huntsville, Alabama, testing rocket engines—not something you’d want to do in a city center.

|

Another, more focused look at the interplay between NASA and society from that era is in an episode of the CNN documentary Soundtracks. That series, whose executive producers include actor Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, is intended to show the relationship music has with key historic events, from the 9/11 attacks to the fall of the Berlin Wall. One of episodes, slated to air at a date to be determined later this spring (the shows were scheduled to air Thursday evenings, but have been shown only intermittently), is titled the “Space Race.”

| Both the book and the documentary show the importance of viewing space history in a broader context: not just an examination of particular programs or missions, but how they fit into a broader cultural and political picture. |

The episode, screened earlier this month at the National Air and Space Museum, starts with the Apollo 11 landing, but then goes both backwards, to the beginning of the space race, and forward, though the 1970s and up to the Challenger accident in 1986. The show is a history of those events through a filter of the music of those eras: David Bowie’s “Major Tom,” of course, but also Sun Ra and Parliament-Funkadelic in the ’70s. Interspersed throughout the 45-minute episode are interviews with a wide range of people: musicians like David Crosby and Billy Bragg, former astronauts and mission controllers, historians, and even the seemingly ever-present Neil deGrasse Tyson.

A panel discussing the show after its screening praised it for bringing together the history of the Space Age with the culture of the era. “One of the interesting things I find about the relationship between music and space is there’s a little bit of a tension,” said historian Asif Siddiqi, who also appears in the show. Both can be “mind-expanding,” he said, but the counterculture was also critiquing the establishment of the era, including space exploration, something that comes through in the show.

Both the book and the documentary show the importance of viewing space history in a broader context: not just an examination of particular programs or missions, but how they fit into a broader cultural and political picture. At the screening, Margaret Weitekamp, a historian at the museum, noted in the panel discussion that space history is often treated as a “separate track” from the broader history of the era, and that she was pleased to see that tension between space and some aspects of society “recontextualized” in the show. Maher, in the introduction of his book, is critical of many space historians for not doing more to examine cultural and other influences in their studies.

There’s certainly more to be done to put spaceflight in the broader cultural context, be it during the race to the Moon a half-century ago or today. Take, for example, the anecdote that leads off Maher’s book about the astronauts walking out of Hair: why were two astronauts, denizens of what then-NASA administrator Tom Paine called the “Squareland” of mainstream America, attending a play that had become symbolic of the counterculture? Maher writes that Lovell named the Apollo 13 lunar module “Aquarius” in honor of the musical, but in Lost Moon, the book Lovell wrote about the mission with Jeffrey Kluger in 1994, they state that the connection was erroneous: Hair was “a musical Lovell had not seen and had no intention of seeing.” And yet, a month and a half after that famous mission, he and Swigert were in New York to see it—or, at least, part of it, a temporary connection between spaceflight and counterculture.