Pondering the future of the International Space Stationby Jeff Foust

|

| “One thing we know with great certainty about the future of ISS is that 2024 will mark the start of a dramatic transition in human presence in low Earth orbit,” said Babin. |

“Today, ISS has hit, really, a very good stride in its research activities,” said Sam Scimemi, director of the ISS at NASA Headquarters, during a panel session at the conference July 19 that included various commercial users of the ISS, from pharmaceutical giant Merck to Made In Space, a startup with 3-D printers on the ISS and, soon, an experiment to produce high-quality optical fibers there.

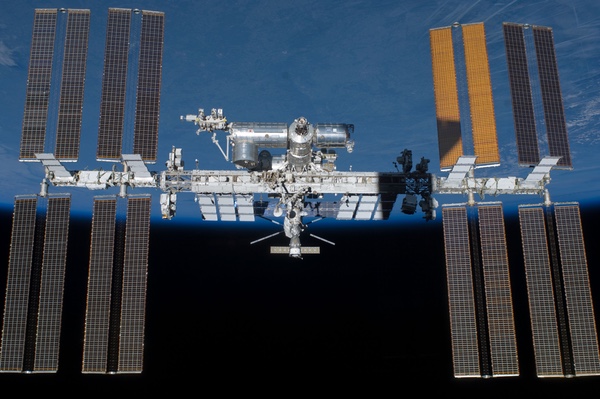

“I don’t think the public realizes how cool ISS is,” Musk said later the same day in an on-stage interview with NASA’s ISS program manager, Kirk Shireman. “It’s a pretty incredible structure that we have orbiting the Earth.”

Throughout the conference, though, during the panel sessions and paper presentations, at breaks and in discussions in a sometimes-congested exhibit hall, there was an undercurrent of uncertainty. Just how long will the ISS, this “incredible structure” in low Earth orbit, be around?

NASA and the other international partners have committed to operating the station through 2024. But what happens after that remains unknown. Some of the commercial partners using the ISS, hailed at the conference, want answers sooner rather than later.

A section of the NASA Transition Authorization Act of 2017, signed into law in March, directs NASA to develop an “ISS transition plan” by December 1, with updates every two years thereafter through 2023. That plan requires NASA to assess both its research on the ISS to support the agency’s exploration objectives as well as development of commercial activities in LEO. It also calls for cost estimates of extending ISS to 2028 and 2030, and an evaluation of the “feasible and preferred service life” of the station, among other requirements.

NASA hasn’t said much about the work on that transition plan, and how interested it would be in another extension. Agency officials have argued in the past that they believe they can complete the research they need to do on the ISS to support its exploration goals, from mitigating human health risks for long-duration spaceflight to developing life support systems for such missions, by 2024.

Robert Lightfoot, the acting administrator of NASA, suggested that decisions about the future of the ISS would go beyond simply determining if NASA has met its research goals on the station. There are also, he said, policy issues, including concerns about another gap in human spaceflight and NASA’s role in fostering economic development in LEO.

“I think we need a vibrant low Earth orbit economy,” he said in a speech at the conference July 19. “If we leave low Earth orbit without that vibrant, established economy, is that the place we want to be?”

Some think the ISS will be around as long as NASA believes it can make use of it. “The idea is that the decision point is one of utility as opposed to calendar,” said Jeff Bingham, a retired Senate staffer who worked on space issues, during a July 19 panel.

| “I think the thing that we have to guard against is this notion that, somehow, we have to make this decision right now,” said Dittmar. |

The emphasis throughout these discussions was on the word “transition.” That is, rather than an abrupt end, an expectation that there will be a glide path from the ISS today to the commercial space stations of tomorrow. No one really knows, though, how that transition might take shape.

“One thing we know with great certainty about the future of ISS is that 2024 will mark the start of a dramatic transition in human presence in low Earth orbit,” said Rep. Brian Babin (R-TX), chairman of the space subcommittee of the House Science Committee, during a speech at the conference July 18.

“No one knows if that transformation will mean deorbiting the ISS, modifying it and extending operations, or establishing a cost-sharing arrangement or distributing human presence to other, as yet unlaunched, habitats,” he added. “These are decisions that will be strongly informed by what people like you can do and learn in the coming years.”

One of those providers of “as yet unlaunched habitats” is Bigelow Aerospace. At the conference, Robert Bigelow reiterated past statements that his company would have two of its B330 expandable modules, each offering 330 cubic meters of volume, ready for launch by the end of 2020. How they will be used, though, remains to be seen.

“With regards to the ISS transitioning, I think that process has begun, in the sense that certainly the discussions have started, the thinking has begun,” he said. He cited as one example of that thinking NASA’s Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships (NextSTEP), which is funding studies of habitation modules that could be used for both NASA’s deep space exploration needs as well as commercial space stations in LEO. Bigelow is one of several companies with NextSTEP awards.

“I don’t look at the ISS as a zero-sum game,” he said. “The transition process ought to be something that’s in parallel, and that the private sector should mature its spacecraft and be able to offer something to NASA that NASA is able to test and to outfit.” That could, he said, result in “multiple platforms doing very diverse kinds of activities, as opposed to having things all aggregate on just one platform.”

A full-scale model of Nanorack’s airlock module on display at the ISS Research and Development Conference. (credit: J. Foust) |

Another company involved in NextSTEP is Nanoracks. It has a study contract in cooperation with Space Systems Loral and United Launch Alliance for Ixion, a concept that involves converting a Centaur upper stage into a commercial space station module. Jeffrey Manber, CEO of Nanoracks, said at the conference July 20 that the company is halfway through its five-month study contract. “Everything is going very well looking at the technical aspects of reusing existing upper stages for commercial habitats,” he said.

Ixion is part of an evolution of Nanoracks from a company that initially provided space for small experiments on the ISS and, more recently, for arranging launches of cubesats from the station, an unanticipated early success for ISS commercialization. Nanoracks is now moving ahead with development of a commercial airlock module it plans to install on the ISS in 2019.

| “I respectfully ask that, by 2019, we know the end date for station services, whether it’s 2024, whether it’s 2028,” Manber said. “The date to me is not as critical as the certainty.” |

Manber, testifying before the Senate Commerce Committee’s space subcommittee July 13, called Nanoracks a “commercial space station company.” The planned airlock module and other work, he said, will “develop the technical expertise and hardware base to own and operate our own space stations, a realistic goal that we've set for ourselves as US policy has matured.”

At the conference, some suggested there was no rush to make a decision on what the transition should look like, including whether and how to extend the ISS beyond 2024. “I think the thing that we have to guard against is this notion that, somehow, we have to make this decision right now,” said Mary Lynne Dittmar, president and CEO of the Coalition for Deep Space Exploration, during a policy panel at the conference July 19. The station, she argued, is a very capable research platform, and research doesn’t always work on set timetables.

“Yes, a decision needs to be made,” she added, “but let’s give NASA at least the chance to finish the transition that it’s trying to work on right now, so we can at least get that information as we start to think about how to do that.”

At the Senate hearing, though, Manber was arguing for a decision to be made, if not right away, then at least fairly soon. “I respectfully ask that, by 2019, we know the end date for station services, whether it’s 2024, whether it’s 2028,” he said. “The date to me is not as critical as the certainty.”

That certainty is vital, he said, in order for him to successfully raise private capital needed for a commercial station that would be ready by the time the ISS is retired. “We in the private sector can then begin to prepare,” he said. “I think we’ll be ready before 2024, but if the station is there to 2026 or 2028, fine, so long as we have certainty.”

Manber also said that he was “pleasantly surprised” with how seriously NASA was taking issues associated with transitioning from the current ISS model to future commercial space stations. “These are complex issues, I recognize that, and I’m very pleased at how much our NASA colleagues are looking into this,” he said.

A NASA official at the same hearing offered a similar view. “I think that it’s important to work together with the government, with Congress and the private sector, to come up with a date that we want to transition from the space station,” said Bob Cabana, director of NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, at the same Senate hearing.

“But,” he added, “we have to ensure that there is something to transition to.”