SpaceX prepares to eat its youngby Dick Eagleson

|

| The most surprising thing, to me, was the flat declaration by Musk that SpaceX's entire current—and imminent—product line is now on track to be sunsetted in an orderly fashion over the next few years. |

I have been quite public in maintaining that SpaceX would keep the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy in service for an extended period as cash cows. I was also publicly of the opinion that Falcon Heavy, and perhaps even Falcon 9, would get new Raptor-powered upper stages and bigger payload fairings. I was, additionally, an advocate of the notion that Dragon 2 would eventually get its landing legs back in order to better serve upcoming commercial low Earth orbit platforms and serve as the basis for, if not Red Dragon to Mars, then a “Gray Dragon” aimed at hosting intrument payloads to land on airless solar system bodies.

All wrong! Turns out I had more of a sentimental attachment to the Falcon family than Elon Musk does. Like Messrs. Martin, Benioff, and Weiss, Elon Musk is also perfectly willing to “kill Sean Bean” in service to a larger cause. To my detractors on these points, I can only say, “You got me.” Mr. Musk is going all-in with BFR and doing so at the best speed he can manage.

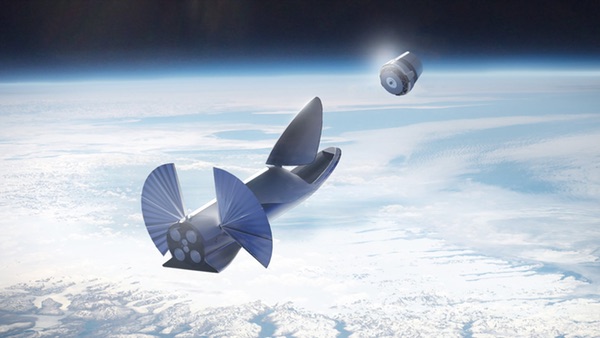

And he is doing so in “run what you brung” fashion. Many of the changes to BFR from the Interplanetary Transport System (ITS) seem aimed squarely at minimizing the time to reach initial operational capability. The decrease in diameter from 12 to 9 meters allows fabrication of BFR in SpaceX's existing Hawthorne factory, so scratch the time needed to build a bespoke factory elsewhere. The Raptor engine version slated to power BFR seems likely to be either the same as, or only a modest upgrade of that which has already been tested at McGregor. The 42 Raptors of ITS would have produced 685,000 pounds-force each at sea level. The 31 Raptors of BFR will produce 385,000 pounds-force each. So a smaller BFR powered by smaller Raptors is intended to allow a first Mars mission of twin BFR's by 2022 in place of now-cancelled Red Dragons.

Looking at the economics of the newest BFR, absent the haze of sentiment, I see why Elon is, in essence, announcing the coming phase-out of Falcon 9, Dragon 1, and even of Falcon Heavy and Dragon 2 before the latter have made their first flights. All will still fly and do useful work, but BFR is an even more productive cash cow than the Falcons and Dragons could have been if kept in indefinite production and service. With BFR there is no non-recoverable second stage, no problematical payload fairing, no time-consuming ride back to port on drone ship for the first stage. For ISS crew and cargo there is no comparable ride back to port for a capsule splashing down in an ocean. BFR is 100 percent recoverable, 100 percent “feet-dry,” and, literally, gas-and-go.

The variable cost per mission of BFR is dominated by propellant. Given that LNG is cheaper than RP-1, a full propellant load for BFR may not cost a lot more—maybe not even as much—than one for an Falcon Heavy. The Falcons already provide SpaceX with very handsome gross margins per mission. BFR will considerably improve those numbers.

Not that everything will be smooth sailing. The logistics of getting assembled BFR's out of the Hawthorne factory and to any of SpaceX's launch sites, for instance, should be, well, interesting.

| BFR booster stages will be even bigger than the shuttle’s external tank. Just how SpaceX will go about moving these behemoths is something I will be eagerly waiting to see explained. |

My wife and I were two of thousands who lined the route of march as a Space Shuttle External Tank was moved from its landfall at a marina to the California Science Center over ten or so miles of Los Angeles surface streets last year. The progress was glacial and the trip took most of a day as signs, wires, and traffic signals had to be moved out of the way and then replaced as the tank wended its way to where it will become part of a massive Shuttle exhibit in a couple more years.

BFR booster stages will be even bigger than the shuttle’s external tank. The BFR's “aspirational” schedule, as announced in Australia, doesn't seem to allow for the Boring Co. to push a giant tunnel from Hawthorne to the Port of Los Angeles docks, so just how SpaceX will go about moving these behemoths is something I will be eagerly waiting to see explained. Living, as I do, just a few miles from Elon's Friendly Neighborghood Rocket Factory, my interest is more than academic.

But that's all SpaceX inside baseball. The impacts external to SpaceX of BFR's pell-mell advent will be many and even more consequential.

For the rest of launch services industry: A propellant-dominant mission variable cost structure provides margin to keep launching and making some money even in the face of anything but outright giveaway levels of subsidy by any foreign government or private launch services competitor. I don't see any governments or private operators being likely to actually try such a thing, but BFR’s economics serve pretty effective notice that there would be no point in making the effort.

For NASA: SLS is now certifiably toast. Elon slit its throat in Adelaide. How long it will take the shambling corpse to notice it is dead and actually fall down is now a matter for the Vegas oddsmakers. Aside from the sporting question of whether the first BFR test flies before SLS EM-1 gets off the ground, BFR will provide the capability to put 20 metric tons more payload at a whack into LEO than even the decade-distant-at-best SLS Block 2. That’s over twice as much LEO throw weight as the anemic SLS Block 1 and almost half again more than the SLS Block 1B. Oh yeah, SLS costs $2 billion a copy, is production-limited to two missions per year, max, and is expendable. BFR, once built, will fly for close to the cost of propellant, will be able to do so on an extremely short turnaround, and will be 100 percent reusable. Did I mention that BFR's payload volume will also be bigger than SLS's? Somebody play Taps already.

Also for NASA: The Deep Space Gateway is now certifiably toast. When a 2-BFR mission can put 150 tonnes on the Moon and bring 50 tonnes back many times per year, it becomes straightforwardly possible—if I may indulge an American West analogy—to quickly and cheaply put as many Ponderosa main houses as one cares to on the actual lunar surface (or subsurface). By that standard, the notional DSG is just a “line shack” out in the middle of nowhere.

| The twin changes of SpaceX's message at this year's IAC compared to last year’s are those of speed-up and autarky—going it alone—regarding BFR. |

Yet again for NASA: Space-borne astronomy and planetary science could be a lot cheaper if sponsoring groups could take advantage of BFR’s ample Earth-escape throw weight to not build probes that are prodigies of light weight. More savings yet could accrue from making maxium use of the cavernous payload bay of the freighter version of BFR’s upper stage to avoid all the origami engineering needed to get probes inside existing payload fairings. Such projects, when BFR's many advantages make them cheap enough, are increasingly likely to originate outside of NASA's ambit.

The next major space telescope after the James Webb Space Telescope, for example, might cost as little as two to five percent of the Webb's $9 billion budget. This could also allow it to have a sizable family of siblings. BFR can put things almost 9 meters across and massing up to 150 tonnes into LEO. Refueling allows such a payload to be dispatched from LEO to pretty much anywhere. The Steward Mirror Lab at the University of Arizona has been making one-piece, 18-ton (16.4 tonne) 8.4-meter telescope mirrors for two decades. Each one costs in the low tens of millions of dollars. I’m sure the folks at Steward could make some consortium of academic institutions, foundations, and philanthropists who like their names on things a nice quantity discount deal on enough mirrors to pepper the whole solar system with instruments each having over a dozen times the light-gathering power of Hubble. Need I say more?

For Blue Origin: Elon has seen Jeff Bezos his 7-meter payload fairing and raised him 2 meters. And, in addition, done away with the fairing entirely in favor of a door that comes back along with the rest of the freighter version of the BFR spaceship. He's also rendered the economics of New Glenn’s non-reusable upper stage(s) problematical by, in essence, doing with BFR what Blue Origin doesn't plan to do until New Armstrong. “Gradatim” may simply not be fast enough to keep up.

For Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic: Elon’s Adelaide presentation about point-to-point suborbital service on Earth is more problematical of accomplishment than the purely space-related aspects of BFR. But if SpaceX establishes this service on even one such route, it pretty well kills the nascent sub-orbital space tourism business as currently envisioned by both Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin. Even at Concorde-like ticket prices, an antipodal BFR flight would cost a small fraction of what both Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin seem set to charge. The flights would also last much longer and involve much more zero-G time than the flight profiles planned by Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin. Plus, you'd actually get to go somewhere instead of just up and back. But the real killer is that the space tourists might well be outnumbered by in-a-hurry businesspeople who are willing to pay for speedy transort and might see also getting a set of astronaut wings as just a nice souvenir of the trip.

The twin changes of SpaceX's message at this year's IAC compared to last year’s are those of speed-up and autarky—going it alone—regarding BFR. Last year, I think, Elon was still hopeful that he could convince NASA into joining his ITS-based Mars crusade and bring some non-trivial government cash to the marriage too. Over the intervening year, though, SpaceX's relations with NASA have, on net, appeared to deteriorate.

The ISS people have thrown in with SpaceX and seem to be increasingly embracing practical reusablity. SpaceX has friends other places within NASA as well.

| The revised BFR plans are, in part, a way of minimizing future NASA and congressional leverage over what SpaceX does. The BFR revisions showcased in Adelaide are, in addition to being a roadmap, also a battle plan. |

Elsewhere in NASA, not so much. For the last couple years, there has been a surly sort of truce in place about CRS and Commercial Crew vs. SLS/Orion. But I think the Falcon Heavy-Dragon 2 “tourist” flight around the Moon announced in February put the noses of both the SLS/Orion crew and other Deep Space “territorialists” within NASA seriously out of joint. The most visible result of NASA’s internal divisions over SpaceX, and commercial space more generally, has been the hard line taken about propulsive landings for Dragon 2.

Musk now realizes, in my opinion, that there is no significant NASA money in prospect for his Mars project and also that there is still a sizable bloc in NASA and Congress alike that still cherish hopes of smacking down SpaceX and restoring the status quo. The revised BFR plans are, in part, a way of minimizing future NASA and congressional leverage over what SpaceX does. They are also a way of simultaneously holding a numberof traditional NASA and congressional “rice bowls” at risk. The Old Boy Network has long been used to being able to squish troublemakers pretty much at will. SpaceX, though, is not only willing, but quite able, to fight back. The BFR revisions showcased in Adelaide are, in addition to being a roadmap, also a battle plan.