Virgin Galactic, Richard Branson, and Finding My Virginityby Jeff Foust

|

| “Richard always poses a challenge, he likes to push us pretty hard,” Moses said. “Sometimes I wish he wouldn’t talk so much.” |

When that happens depends on whom you talk to. Virgin Galactic officials are very circumspect when talking about schedules, emphasizing that they will fly the second SpaceShipTwo into space, and begin commercial flights, only when it is safe to do so. “We’re now right at the edge of powered flight,” company CEO George Whitesides said at the Mars Society’s annual conference in Southern California last month. Asked when commercial flight would begin, he responded, “When we’re done with the test flight program. We’ve got to wait until we think it’s safe.”

Virgin Galactic founder Richard Branson, though, has often been willing to give schedules, even those that those in the company itself might consider unrealistic. Interviewed recently by the Nordic edition of Business Insider, he declared, “We will hopefully be in space in three months, maybe six months before I’m in space.”

Asked about those comments at last week’s International Symposium for Personal and Commercial Spaceflight in New Mexico, Virgin Galactic president Mike Moses offered a response. “Richard always poses a challenge, he likes to push us pretty hard,” he said, according to a local newspaper. “Sometimes I wish he wouldn’t talk so much. We hope to be in space by the end of this year. We’ll take our time with it. We’re going to fly when we are ready.”

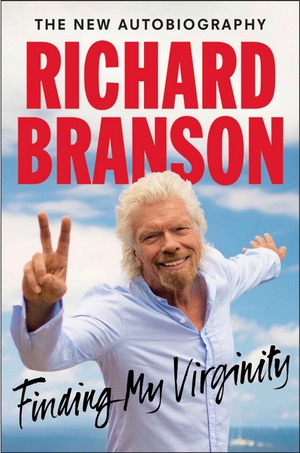

Into this exchange of views comes Branson’s latest autobiography, Finding My Virginity (Portfolio, 480 pp., $35.00), published last week. The book, a sequel of sorts to his earlier autobiography Losing My Virginity, focuses on the last two decades of his life, in particular his wide range of business ventures in aviation, trains, banking, and, yes, spaceflight.

Branson’s recollections about the development of Virgin Galactic are spread out over several chapters in the book, interspersed with others about his various other ventures or personal life. Those chapters trace the development of Virgin Galactic from the discovery of SpaceShipOne at Scaled Composites (during a visit to check on the progress of the Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer airplane) through the Ansari X PRIZE and then the extended development of SpaceShipTwo, including the 2007 test stand accident that killed three Scaled employees and the 2014 crash of the first SpaceShipTwo.

| “With so much riding on our space program,” Branson writes, “we had to control costs tightly elsewhere, manage our cash carefully and be very stringent with other investments.” |

Branson, according to his recollection, convinced Paul Allen, the Microsoft co-founder who funded the development of SpaceShipOne, to continue development once the vehicle won the prize. “The government isn’t going to start sending people to space again—it’s up to us,” he recalls telling Allen, apparently oblivious to the ongoing human spaceflight programs of several countries. “If you put SpaceShipOne in a museum, we’re losing the chance of a lifetime—of many lifetimes.”

SpaceShipOne, of course, did end up in a museum—the National Air and Space Museum in Washington—but Allen did agree to license the technology, leading to the development of SpaceShipTwo under a deal that included Scaled. “We debated ships big enough for four, six, even ten people,” Branson recalls, before settling on the design of six passengers and two pilots. Scaled “came back confident they could scale up SpaceShipOne’s smaller design into a beautiful, functional, safe aircraft.”

The day of the 2007 engine test accident “should have been a great day for Virgin Galactic,” Branson said, as the company planned to announce the winner of the design competition for Spaceport America in New Mexico. The book doesn’t provide any additional insights into that cold-flow test incident, but Branson describes Burt Rutan as “literally broken-hearted” afterwards, thinking the stress of the accident contributed to a cardiac condition. Branson, though, “concluded we should press on.” The changes caused by the accident investigation, including replacing a carbon fiber oxidizer tank with an aluminum one, set development “back a long, line time, and cost a huge amount of money, but it was obviously the right thing to do.”

The accident and other development issues put a strain on Virgin, though, as Branson alludes to on several occasions in the book. “With each breakthrough, however, new costs arose, and we really needed an investment injection to maintain momentum,” he writes of the progress the company had made as of 2009. That led to the $280 million investment by Aabar, which he said came out of a meeting he arranged on little notice with the deputy prime minister of the United Arab Emirates.

“Until this point the company had been wholly owned and funded by Virgin Group, which put a strain on our wider operations,” he said. “With so much riding on our space program, we had to control costs tightly elsewhere, manage our cash carefully and be very stringent with other investments.”

A couple of chapters are devoted to the 2014 SpaceShipTwo accident and its aftermath. A good chunk of that section is devoted to criticizing the media for its handling of the accident, jumping to conclusions that the engine on the vehicle exploded. (It was, in the hours after the accident, the most likely cause; it wasn’t until more than 48 hours after the accident that investigators noted the premature unlocking of the vehicle’s feathering system, something even Scaled and Virgin didn’t foresee when designing the vehicle.)

| “On the day we started, if I had known it was going to take twelve years I suspect I wouldn’t have gone ahead with the project either—we simply couldn’t afford it.” |

“In my opinion, 99 percent of the press are very good,” he writes, but that doesn’t stop him from criticizing everyone from the Associated Press to British television journalist Jon Snow to “a local blogger [who] falsely claimed to have seen SpaceShipTwo’s engine sputter and fail to perform.” Only after venting about that coverage does Branson turn his attention back to the human loss from the accident—the death of copilot Mike Alsbury—and the implications to the business.

“Back at Virgin HQ I knew I was in a minority in wanting to continue,” he writes of the deliberations within the company about whether to keep developing SpaceShipTwo. “But that didn’t stop me—I believed in the project, believed in the team and believed in the vision.” Virgin, of course, did decide to continue work on SpaceShipTwo, with the second spaceplane soon expected to begin the same powered flight tests that the first one was when it was lost.

Branson does sound chastened by the accidents and setbacks. “I felt the company would be unlikely to survive another accident,” he writes of his feelings after the 2014 crash. “If I hadn’t owned the company, I think the program would have been knocked on the head some years ago. On the day we started, if I had known it was going to take twelve years I suspect I wouldn’t have gone ahead with the project either—we simply couldn’t afford it.”

He adds, though, he’s not giving up on Virgin Galactic now, regardless of the business case. “It’s never been just a business to me,” he says. While commercial human spaceflight can be profitable, that’s not the main point for him. “I believe that putting our faith in space travel serves, quite literally, a higher purpose.”

Finding My Virginity offers those and other interesting insights about Virgin Galactic and his other businesses. He’s not, though, a stickler for accuracy on facts like dates. In the passage where he writes about how a Virgin employee stumbled upon SpaceShipOne under development, he states the event took place in “mid-2003,” but that is off by at least a year: Scaled unveiled SpaceShipOne publicly in April 2003. Later, he writes that Virgin was ready to reveal the design of WhiteKnightTwo in January 2008; while the company may have been ready then, the plane was formally rolled out in an event in Mojave in July of that year.

Near the end of one chapter, he recounts seeing the first glide flight of the second SpaceShipTwo last December alongside Brian Cox, the physicist and television personality who, Branson recalls, became convinced he wanted to fly in space on that vehicle. And when might he, Branson, or the 700 other current customers of Virgin Galactic get that chance? This time Branson doesn’t give a specific timetable. “Hopefully that moment will come very, very soon.”