Back to back to the Moonby Jeff Foust

|

| “I believe that we’re on the verge of a new era in lunar science and exploration,” said Neal. |

On October 5, Vice President Mike Pence formally confirmed what most in the space community had long expected: US space policy was being changed to redirect humans back to the Moon. “We will return American astronauts to the Moon, not only to leave behind footprints and flags, but to build the foundation we need to send Americans to Mars and beyond,” he said, leaving the details of how to do so up to NASA.

While hardly unexpected—the administration had been telegraphing such a shift for months—the announcement gave a green light for lunar exploration advocates, in industry, academia, and government, to make a new push for robotic and human missions to the Moon, for science and commerce.

In a fortuitous coincidence, less than a week after that meeting of the National Space Council was the annual meeting of the Lunar Exploration Analysis Group (LEAG) in Columbia, Maryland. The resurgence in interest in the Moon attracted what organizers said was the largest turnout for a LEAG meeting since 2005, when the Vision for Space Exploration—and its call for a human return to the Moon by 2020—was still in its early phases.

“I believe that we’re on the verge of a new era in lunar science and exploration,” said Clive Neal, the outgoing chairman of LEAG, in comments at the beginning of the two-and-a-half-day meeting.

There was enthusiasm about that redirection back to the Moon and the LEAG meeting and a separate “Back to the Moon” workshop that immediately followed. That doesn’t mean, though, that attendees were expecting, or desiring, a return to the days of the Constellation program of a decade ago.

“If a national commitment has been made to return to the Moon, how do we get NASA behind it?” asked Paul Spudis of the Lunar and Planetary Institute during a panel discussion that started the Back to the Moon workshop. He looked back to both the Vision for Space Exploration and the earlier Space Exploration Initiative. “You’d think with a Moon commitment that NASA will be all enthusiastic. But the previous two times that’s happened, NASA was among the least enthusiastic people in the room when it came to returning to the Moon.”

“The main thing that NASA is going to need is sustained funding,” said Apollo 17 astronaut and former senator Harrison Schmitt. “The Constellation program, from my point of view, did not have enough momentum to survive a change in administrations primarily because the projected needs of the Constellation program were not met in terms of financing.”

Tied to that, argued Spudis, was a lack of singular rationale for the program. “We need to develop what I call a mission statement,” he said, “a single, declarative sentence that summarizes why we’re going to the Moon.”

He said he wanted something similar during the development of the Vision for Space Exploration, but was unsuccessful. “NASA didn’t want to hear it. They came up with 186 objectives and six themes. They didn’t want to summarize it in one statement. My argument is, if you can’t state your mission in a single statement, there’s a good chance you don’t know what it is.”

NASA right now doesn’t have that mission statement, or a plan for a human return to the Moon, only the comments by Pence at the council meeting and his call to NASA to submit a plan within 45 days, including identifying the resources needed.

| “You need a continuing human presence in space,” Crusan said. “If you just have a sortie-based program, at any point anyone can end those flights.” |

That plan will leverage work already underway at NASA. “We were already in work doing an exploration report that was actually required by Congress,” said Jason Crusan, director of the agency’s advanced exploration systems division, at the LEAG meeting. That’s a reference to an exploration roadmap, outlining the steps needed to get humans to Mars, perhaps by way of the Moon, required by the NASA authorization act signed into law in March.

That roadmap report is due to Congress in December, shortly after the 45-day report is due to the White House. “We’re using a lot of that work being done for the exploration report to answer this 45-day response time that we have,” Crusan said. “How would we enable human return [to the Moon] given the constraints that we all have?”

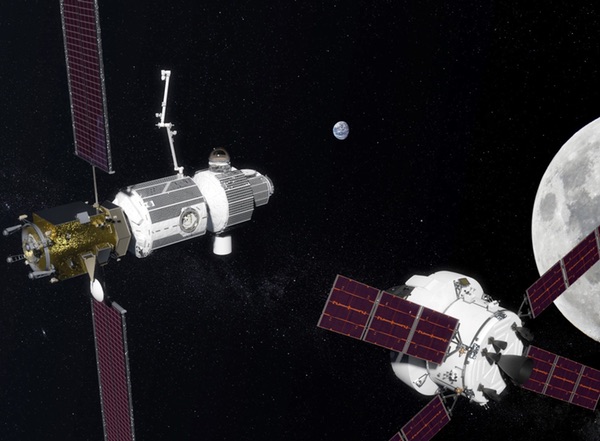

Crusan suggested that the Deep Space Gateway, the outpost in cislunar space first publicly proposed by NASA earlier this year, would play a role in that plan. “Can you enable human return through a gateway-type infrastructure? Can you enable robotic missions that way initially, and fold in human return that way?”

The alternative, he said, would be a direct human return to the Moon, but Crusan cautioned that approach, in his opinion, may not be sustainable. “You need a continuing human presence in space,” he said. “If you just have a sortie-based program, at any point anyone can end those flights.”

He added that NASA’s budget is constrained for the next several years because of the combined development costs of the Space Launch System, Orion, commercial crew vehicles, and flagship NASA science missions. That leaves limited funding for major new development programs needed for a human return to the Moon, including landers and surface systems. The Deep Space Gateway, though, could fit into those budgets and provide the presence to enable later landing missions.

“I’m not a big fan of just going to direct return,” he said. “Because with direct return, we have many, many steps to go before we have permanent presence.”

Moon Express suggested its first mission might not be a lander (above) but instead a lunar orbiter. (credit: Moon Express) |

International and commercial roles

NASA has had talks with other space agencies about the gateway. Robert Lightfoot, the acting administrator of NASA, said at the International Astronautical Congress in Australia last month that there had been discussions dating back to April about the Deep Space Gateway but—contrary to some media reports that NASA and Roscosmos had agreed to cooperate on its development—no deals regarding its construction.

“What we really said in our discussion is, as we move out from ISS, we want to take advantage of that with all our partners, and whatever we do, we do it in a global way,” Lightfoot said at the conference. “There’s no commitment of resources or commitment to a program. It’s all conceptual at this point.”

| The proposed Deep Space Gateway “also, very importantly, provides an onramp for international and commercial partners,” Carpenter added. |

The idea of a gateway as a staging point for both human and robotic lunar missions has support in the international community. “This has become a fundamental part of our architectures,” said James Carpenter of ESA at the Back to the Moon workshop. The gateway, he said, allows for “affordable infrastructure buildup” in cislunar space while the International Space Station remains in operation. “We can start doing something now.”

The gateway, he said, offered other benefits as well. It could be a “safe haven” for crews needing to leave the lunar surface. It could serve as a communications relay, particularly for missions on the lunar farside out of view from the Earth, and support teleoperations of robotic vehicles on the lunar surface.

“It also, very importantly, provides an onramp for international and commercial partners,” he added.

Among those potential international partners is Canada. “We’re in a process right now of defining a new vision for Canadian exploration activities,” said Victoria Hipkin of the Canadian Space Agency at the LEAG meeting. “The Canadian government has asked us to define options for future contributions to deep space exploration.”

One option, she said, is to provide “lunar surface mobility” for future missions, with concept studies of a pressurized rover. “What we understand is that for any contribution that Canada is going to make, the government would be very keen that it will maintain, into the future, a Canadian astronaut program.”

Those increased opportunities for international partners is one difference from NASA’s previous lunar plans. Another, and perhaps bigger, difference is the growth of commercial capabilities to support lunar exploration.

At the LEAG and Back to the Moon meetings, four companies—Astrobotic, Blue Origin, Masten Space Systems, and Moon Express—all discussed their plans for commercially-developed lunar landers, all in varying stages of development.

Moon Express, the only company currently competing for the Google Lunar X PRIZE, emphasized its plans announced earlier this year to develop the MX series of landers, starting with the MX-1E that could attempt to win the prize early next year (see “The Moon is a harsh milestone”, The Space Review, July 24, 2017).

However, Spudis, who is also an adviser to Moon Express, hinted at a change of plans. “We’re actually thinking about flying an orbiter first,” he said at the LEAG meeting. “An orbiter will test out all the different spacecraft systems. It’s a fairly low-risk mission. We have a variety of things that we can still do from orbit around the Moon.” The orbiter would launch next year, followed by a lander “soon after that,” which he acknowledged could slip to 2019. That would put the company out of the running for the prize under the current rules, which require teams to complete their missions by the end of March 2018.

Astrobotic, which dropped out of the competition last year, is focused on developing its first Peregrine lander for launch in 2019. The initial mission will carry 35 kilograms of payload for an eight-day mission after landing, said Astrobotic’s Dan Hendrickson at the LEAG meeting, but could be expanded to up to 265 kilograms on future missions using the same platform.

| “If there’s anything that I know about this new administration, is that they want something that’s bold,” said Pittman. |

Masten Space Systems is working on its XL-1 lander, based on technologies it has been developing and testing on its series of technology demonstration vehicles. “The idea for this lander is to get it there efficiently and as cheaply as possible,” said Masten CEO Sean Mahoney at the Back to the Moon workshop. The design for XL-1, he said, recently completed its critical design review, with a terrestrial demonstrator under construction.

That lander will be relatively limited in performance, with a payload capacity of 100 kilograms, he said, and won’t have the ability to go to the lunar poles. But XL-1, he said, isn’t the only lunar lander on its drawing board. “XL-2 can do it,” he said of missions to the poles.

Blue Origin made another pitch for its Blue Moon cargo lander concept at the meeting, a design that would be able to carry up to 4.5 tons of cargo to the lunar surface and be compatible with a variety of launch vehicles, including the company’s own New Glenn.

Blue Origin’s A.C. Charania emphasized, as other company officials have in the past, that it would seek to develop Blue Moon as part of a public-private partnership with NASA. “We’ve been very explicit publicly over the last few months that we want to go together to the Moon with NASA,” he said. “We don’t view Blue Moon in isolation.”

How those partnerships will develop is another issue facing NASA and the White House as they turn Vice President Pence’s call for a human return to the Moon into an affordable plan. There was consensus, though, that those growing commercial capabilities, plus the ability to, at least in the long term, leverage lunar resources like water ice to sustain activities there more affordability, will have to play a key role in any exploration architecture that comes out of the ongoing studies.

“We need to think bigger and we need to think bolder,” said Bruce Pittman of the Space Portal office at NASA’s Ames Research Center at the LEAG meeting. “If there’s anything that I know about this new administration, is that they want something that’s bold.”