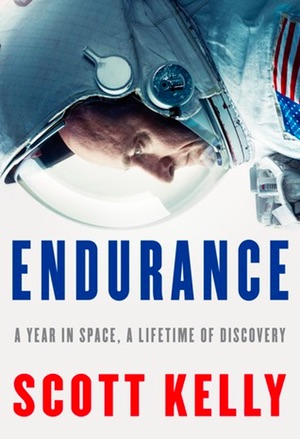

Review: Enduranceby Jeff Foust

|

| Reading Wolfe’s book “had given me the outline of a life plan” he intended to follow. |

But, as he describes in his memoir Endurance, that’s not really true. What inspired him instead was reading Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff as a college freshman. “I’d never read anything like it before,” he recalls. “I felt like I had found my calling. I wanted to be like the guys in this book, guys who could land a jet on an aircraft carrier at night and then walk away with a swagger.”

At that time, he acknowledges, that career path seemed unlikely. He did poorly in high school, uninterested in his classes, and was continuing that trend in college (he spent his freshman year at the University of Maryland Baltimore County, having applied there by accident instead of the main campus in College Park.) He was more likely to be partying then to be studying. But, he says, reading Wolfe’s book “had given me the outline of a life plan” he intended to follow.

Of course, we know he successfully followed that path: he transferred colleges, became a naval aviator and then a test pilot, and was selected to NASA’s astronaut corps in the mid-1990s at the same time as his twin brother Mark. His NASA career involved two shuttle missions and then two expeditions to the International Space Station, including his nearly one-year in space in 2015–2016.

In Endurance, Kelly takes a dual-track approach, alternating chapters telling his life story leading up to that year-long mission with the mission itself. The former set of chapters follows a familiar trajectory of military flight experience, test pilot training, and then the astronaut selection process, albeit with his unconventional origins. The other set of chapters follows Kelly in detail through his year in space in great detail. That ranges from the day-to-day life on the station to dealing with its various ups and downs, such as arrival and departure of crews, arrival of cargo ships (and the loss of cargo ships—he was on the ISS when both a Progress and a Dragon suffered failures), and walking in space.

Those chapters are, perhaps, the most thorough examination in a book to date about life on the station. He takes readers through both the mundane and exceptional aspects of life in space, from repairing the station’s toilet to doing research, as well as getting along with Russian, American, European, and Japanese crewmates. There are also the challenges of keeping touch with loved ones on Earth, with frequent calls and emails with his partner (now fiancée) Amiko and his daughters from a previous marriage.

| “People often ask me why I volunteered for this mission, knowing the risks,” he writes in the opening. “I have a few answers I give to this question, but none of them feels fully satisfying to me. None of them quite answers it.” |

Kelly, who left NASA not long after returning to Earth last year, is not hesitant to criticize the agency for some aspects of ISS operations. He is particularly critical of its perceived lack of attention to carbon dioxide levels at the station, which he says it allows to be higher than they should, resulting in symptoms ranging from headaches to reduced cognitive abilities. He writes that he tried to get NASA to follow lessons from the Navy’s submarine experience in maintaining lower carbon dioxide levels, without success. Discussing one call with Amiko, he says she can tell when those levels are high on the station based on his mood in those calls. “She is the only person on planet Earth who seems to care,” he concludes.

Kelly doesn’t write much about the aftermath of his long-duration spaceflight, beyond a dramatic opening about feeling ill a couple days after landing, including rashes and swollen limbs. “People often ask me why I volunteered for this mission, knowing the risks,” he writes in the opening. “I have a few answers I give to this question, but none of them feels fully satisfying to me. None of them quite answers it.”

At the end of Endurance, though, he argues the mission was worth it, not just for the medical data collected during the flight but also what he calls the “practical issues” for a long-duration mission. (NASA, he says, is now willing to manage carbon dioxide at the lower levels he desired, and is developing scrubbers that improve upon the balky units on the station that Kelly often found himself repairing.) That makes human missions to Mars feasible, he said, if there’s the will to do so. “I know now,” he writes at the end of the book of such missions, “that if we decide to do it, we can.”