The emerging field of space economics: theoretical and practical considerationsby Vidvuds Beldavs and Jeffrey Sommers

|

| Markets do not exist for products produced from space resources. There are no plausible scenarios for widespread sale of space resources to existing markets on Earth. |

Economics is a social science that studies the operation of systems involving decision-making by actors often in competition with each other regarding production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services under conditions of limited resources and competing interests.1

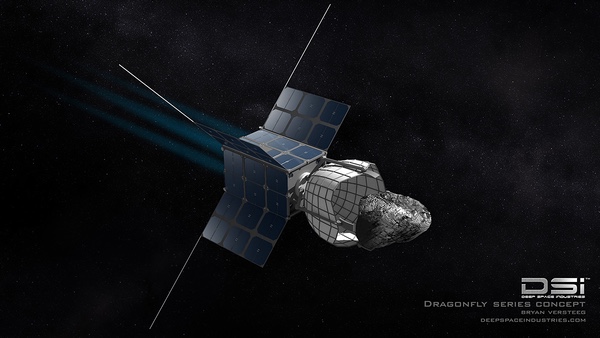

Outer space is often described as a realm of boundless, widely distributed resources spread across great distances and outside of the gravity well of Earth. While there are millions of asteroids and comets with resources of significant value on Earth, some with potential values in the trillions of dollars,2 space resources are extremely difficult to reach and transform into saleable products. As a result, no outer space economy has emerged thus far outside of satellite services provided to users on Earth.

Markets do not exist for products produced from space resources. There are no plausible scenarios for widespread sale of space resources to existing markets on Earth. The very high cost of acquisition and transport to Earth and the time required for transportation would make sale of all but extremely valuable materials to Earth markets unviable. However, even in the case of highly valuable materials, such as platinum group metals and diamonds, the sale of large quantities of highly valuable materials would drive down their price. Significant sale of rare space materials could potentially destroy markets, lessening the allure of the trillion-dollar asteroids containing rare materials.

While the emergence of terrestrial markets for some space resources cannot be excluded and remains a topic of economic analysis, the emergence of such markets cannot be assured, even if production capacity were to be developed. In the early stages of the space economy the most likely value, therefore, of extraterrestrial resources will be in the on-site efficiencies derived from the savings of transportation costs from delivery of materials from Earth. In the longer term, as increasingly large facilities are developed in outer space, particularly if they house and employ large numbers of people, the space economy can become self-sustaining.

Utility of space economics

A field of study can be sustained if it has use and meets needs of society. A utilitarian goal of space economics is to show conditions under which a self-sustaining outer space economy could emerge, despite multiple questions that arise if outer space resources appear to have little market potential in terrestrial markets:

How could the huge investments required for development of infrastructure and enabling technologies needed to develop a self-sustaining space economy be justified unless investors on Earth can realize returns that are competitive with other investments?

If an investment cannot lead to rights to realize economic returns from the investment, it would be irrational. Rights to economic returns from investments, or property rights, or use rights, are a necessary pre-condition of rational investment decisions. If the Outer Space Treaty (OST) excludes economic rights to resources in outer space, how can a space economy even emerge?

| If known technologies can reduce the market value of a resource to a small fraction of its initial value in a defined period, how would this influence decision-making regarding a resource like lunar water? |

Article I of OST states: “The exploration and use of outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development, and shall be the province of all mankind.” How can this statement be interpreted as an economic assertion with operational implications for economic actors rather than just a principle of political philosophy granting opportunities and benefits to humankind as a whole?

If known technologies can reduce the market value of a resource to a small fraction of its initial value in a defined period, how would this influence decision-making regarding a resource like lunar water? Alternatively, massive investments applying known technologies could reduce the acquisition cost of metals such as titanium, iron, and aluminum from lunar regolith significantly below acquisition costs from terrestrial sources. This could enable the creation of large solar arrays and megastructures in near Earth orbits that could deliver electrical power to Earth at highly competitive prices and have the potential for very large returns on investment. However, the timeframe to realize such returns may be in the decades. How can decision-systems be structured to analyze and potentially justify such investments?

Economic actors are implicitly understood as being individual humans or corporations formed by humans endowed with corporate personhood that can make economic decisions. Insofar as outer space activities may be dominated by robots and other artificial entities that may be involved in economic decision-making largely independent of human actors due to extreme distances, space economics need to address what is the role of robotic economic actors in the analysis of economic systems in outer space?

Architecture of space economics

Assuming a space economy emerges and that the issues, challenges, and barriers identified above can be overcome, what are principles and architecture that will define the field of space economics?

OST is viewed as the legal foundation for space law and, by implication, for the rules that will govern space commerce and the functioning of the space economy. But OST defines outer space as a commons3 belonging to all humanity. Sovereign ownership of the Moon and other bodies in the solar system is excluded. The rights to economic benefits resulting from investment is fundamental to market economies. If rights to economic benefits cannot be guaranteed, there will be little if any investment.4 Property rights are one example of rights to economic benefits of an investment. Mining rights and land use rights are other examples. Internationally accepted rules have not been developed for assigning mining or use rights to resources on the Moon or elsewhere in outer space. Domestic laws of many countries largely fail to even reference outer space.

Space economics must address the challenge of ownership rights in outer space in view of the condition that ownership of the Moon and other celestial bodies in the solar system is excluded by OST, and that outer space is the province of all mankind. If this issue cannot be resolved, then needed multi-billion-dollar investments cannot be justified and no space economy can emerge.

The emerging field of space economics potentially includes multiple subdisciplines that draw on analogous disciplines in the terrestrial realm: economics of space development (developmental economics), space resource economics (resource economics), economics of human/autonomous-robotics systems (information economics), lunar economics, Martian economics, multi-planetary economics (macro-macroeconomics?), and more. The range of economics issues to address is considerable and includes political economy. The guarantee or assignment of rights to the benefits of investment in assets is fundamentally a political decision, and as a result a point of discussion in political economy.

Successful economies such as China (and historically when Britain ruled Hong Kong) exclude private ownership of land in urban areas,5 yet millions of individuals have developed great personal wealth and Chinese corporations have become successful global competitors. It appears that a functioning and growing economy can be constructed in the absence of real property rights as understood in some countries. Nevertheless, the recognition of the lawful right to economic benefits from investment in assets is a fundamental condition of a functioning economy.

| Can a functioning and growing economy be constructed based on the principles of the OST? |

Proposals have been advanced to build a solar system civilization6,7 based on the exploitation of the vast resources of the planets, moons, asteroids, comets, and other bodies present in the solar system. How the economy of this solar system civilization is to be built will be determined by the policies negotiated among the participating states and defined in the founding documents covering its formation. Thus far, there is no agreed to process or even a forum to negotiate the rules to govern the emerging outer space economy.

Outer Space Treaty

The Outer Space Treaty (OST)8 is recognized as the foundation of international law pertaining to outer space. Article 1:

The exploration and use of outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development, and shall be the province of all mankind.

Article 2:

Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.

These and other principles embodied in OST define outer space as an international commons. They differ radically from principles followed by states in the Age of Empires when France, Britain, and other European states seized control of territories in Asia, Africa, and the Americas to multiply the benefits to the colonial powers, their national elites, and the commercial businesses therein domiciled. Additionally, if states cannot appropriate territory on the Moon or other celestial bodies, then leasing rights would appear precluded in outer space.

Can a functioning and growing economy be constructed based on the principles of the OST? A functioning and growing economy can be understood as an economy where economic agents can invest financial and other resources to create productive capacity that can process material resources into higher valued products that can be sold at a profit to generate wealth for the owners of the means of production. If the benefit from the use of space accrues to states irrespective of their degree of their economic or scientific development, national laws are needed to translate rights and benefits granted to states to benefit the economic agents, which conventionally are not states but rather are individuals or firms. National space laws in Luxembourg and the US attempt to cover this, but the issue remains that OST language does not recognize the rights of economic agents. Attempts to interpret OST to allow recognition of the rights of economic agents have been criticized most recently by Russia, which claims to “protect the independence of the asteroids.”9

Without an international regime that defines how OST principles can be interpreted to enable a functioning economy, such an economy cannot be constructed. In the absence of an internationally agreed-to process to negotiate rules to govern the emerging space economy, it is useful to consider the Moon Treaty, which was negotiated specifically to provide such a process.

Moon Treaty

The Moon Treaty10 was unanimously accepted by the UN General Assembly on December 5, 1979. It represented an attempt of UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space to attempt to define general principles for the use of the resources of the Moon and other cosmic bodies in outer space. The Moon Treaty is widely considered a failed treaty because only 17 states have ratified it, with an additional four signatories that have not ratified it. No spacefaring power capable of reaching the Moon has done so although two of the signatories, France and India, essentially have such capability.

Like OST, the Moon Treaty defines the Moon and other cosmic bodies in outer space as an international commons. Article 4, par. 1:

The exploration and use of the moon shall be the province of all mankind and shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development. Due regard shall be paid to the interests of present and future generations as well as to the need to promote higher standards of living and conditions of economic and social progress and development in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations.

Article 11:

1. The moon and its natural resources are the common heritage of mankind, which finds its expression in the provisions of this Agreement, in particular in paragraph 5 of this article.

2. The moon is not subject to national appropriation by any claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.

3. Neither the surface nor the subsurface of the moon, nor any part thereof or natural resources in place, shall become property of any State, international intergovernmental or non- governmental organization, national organization or non-governmental entity or of any natural person. The placement of personnel, space vehicles, equipment, facilities, stations and installations on or below the surface of the moon, including structures connected with its surface or subsurface, shall not create a right of ownership over the surface or the subsurface of the moon or any areas thereof. The foregoing provisions are without prejudice to the international regime referred to in paragraph 5 of this article.

The Moon Treaty explicitly calls for the negotiation of an international regime in Article 11, par. 5:

States Parties to this Agreement hereby undertake to establish an international regime, including appropriate procedures, to govern the exploitation of the natural resources of the moon as such exploitation is about to become feasible.

Par. 7 sets forth principles guiding the negotiation of the international regime:

7. The main purposes of the international regime to be established shall include:

- The orderly and safe development of the natural resources of the moon;

- The rational management of those resources;

- The expansion of opportunities in the use of those resources;

- An equitable sharing by all States Parties in the benefits derived from those resources, whereby the interests and needs of the developing countries, as well as the efforts of those countries which have contributed either directly or indirectly to the exploration of the moon, shall be given special consideration.

While at this time the Moon Treaty can be considered as having no effect in matters concerning space development, the principles proposed to govern the international regime offer a starting point that is absent in the OST.

Space economics will consider issues involved in the construction of a functioning and growing space economy made possible by a suitable international regime. How the international regime should be framed is a relevant concern of space economics and will be addressed in Part 2. The pathway to development of such an international regime is a political question that lies outside of the economic issues addressed in space economics.

Endnotes

- Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economics">“Economics”

- Asterank

- Wikipedia, “Commons”

- Hernando de Soto is economist who has shown that the absence of clear property rights for much of the population in poor developing countries is a primary reason for their poverty.

- Urban land in China is owned by the state but usufructuary rights are granted to developers to develop urban land.

- Metzger, P.T., Muscatello, A., Mueller, R.P., and Mantovani, J., (2011), “Affordable, rapid bootstrapping of space industry and solar system civilization”, preprint.

- O'Neill, G. K., (1974) “Colonies in Space”, Physics Today, archived copy.

- Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (1967).

- The Russian foreign ministry told the publication Izvestia “that Russia will offer to make mandatory for all countries the requirement about the impossibility of assigning minerals in space. This initiative will be introduced in April 2018 in Vienna at a meeting of the UN COPUOS Legal Subcommittee.”(Machine translation).

- Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies. Retrieved 2017-07-26