Review: Space Odysseyby Jeff Foust

|

| “I remain the most successful writer in the world who’s never had a movie made,” Clarke lamented to a writer friend before starting work in 2001. |

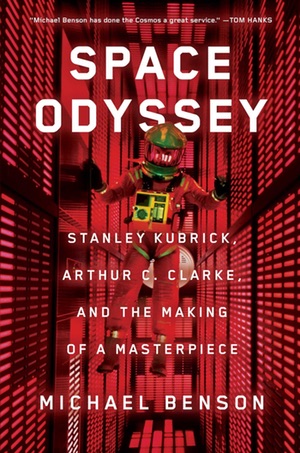

Those initial strong negative reactions to the movie, in Washington and in New York the next day, are well chronicled, as was the sweeping change in opinion in the weeks that followed as lines of moviegoers drowned out the critical reviews (see “Fifty years after the future arrived: the astronauts of 2001: A Space Odyssey”, The Space Review, this issue.) What’s less well known, but superbly chronicled in Space Odyssey, is the effort to make 2001, an epic in and of itself.

While 2001 hit theaters in April 1968, work on the movie started four years earlier. In early 1964, Clarke was living in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), writing science fiction and essays about the new Space Age, but lamenting that none of his work had been adapted for the big screen (his novel Childhood’s End had been optioned by a studio, but never produced.) “I remain the most successful writer in the world who’s never had a movie made,” he lamented to a writer friend. At the same time, nearly halfway around the world in New York, Stanley Kubrick, fresh off the success of Dr. Strangelove, was thinking about his next work, and wanted to tackle science fiction, a genre at the time associated with B-movies. “I want to make the first science fiction film that isn’t considered trash,” he told a friend.

Kubrick became aware of Clarke’s work and the two met in April 1964 in New York, part of a visit Clarke had already planned for other writing. The two hit it off and agreed to collaborate on a science fiction epic—but what that epic would be about took a long time to come together. Indeed, the plot for 2001 continued to evolve even after filming began, much to the consternation of Clarke, MGM, and just above everyone else but Kubrick. “This improvisatory, research-based approach was practically unheard of in a project of this scale,” Benson writes.

Benson provides a detailed and thorough study of the making of 2001 over the four years from Kubrick’s meeting with Clarke to the film’s premiere. The book explains how many iconic aspects of the film came into being, such as the development of the monolith. Originally, Kubrick envisioned a transparent pyramid as the symbol discovered on the Moon, and sent a film designed to a trade fair in London to look into getting it made in Perspex, what Plexiglas was called in England. A company there said they could make it, but it would better as a big slab.

Kubrick later agreed, and the company provided that slab—only to find that, in its completed form, it had a greenish tint, rather than being “magically ultraclear” as Kubrick envisioned. “So, let’s just make a black one,” the designer then suggested. “Okay,” Kubrick responded.

| “Benson states that “2001’s influence remains so pervasive that it’s hard to overestimate.” It’s hard to disagree with that assessment. |

The movie is known for its limited dialogue, although the book notes that there was much more dialogue planned but later cut, and even a mini documentary of interviews with scientists that Kubrick at one time planned as a prelude to the film, only to cut it later: part of what Benson describes as a “calculated ambiguity” that ultimate led people to love, or hate, the film. Benson cites as one example the scene were Lockwood’s character, Frank Poole, is lying on a tanning bed, listening to a happy birthday message from his parents and dismissing it with a “numb flatness” that many considered emotionless. That scene, Benson writes, “transmitted a quietly excoriating message about the desensitizing effects of technologically mediated communications,” one that rings as true today as it did a half century ago.

In the book’s conclusion, Benson states that “2001’s influence remains so pervasive that it’s hard to overestimate.” It’s hard to disagree with that assessment, and this is an ideal book for anyone who has seen the movie and wants to appreciate how it was made and how challenging a project it truly was. This book is extensively researched, and Benson talked with many of the people involved, including Clarke before his death a decade ago (Kubrick passed away in 1999, but Benson did talk with his widow.)

Fifty years later, the Uptown Theater is still in operation in Washington, now formally called the AMC Loews Uptown 1 but just the Uptown for locals. However, on this 50th anniversary of the premiere of 2001 it is not screening that movie but instead another film set decades in the future and made by a famous director: Steven Spielberg’s Ready Player One, depicting a future where cyberspace, rather than outer space, is preeminent. Each era, it seems, gets the cinematic future it deserves.