Space lawmakingby Lucien Rapp

|

| Where new markets emerge, new regulations and laws soon follow. |

Given the international state responsibility for the undertaking of national activities in outer space (Outer Space Treaty (OST), Article VI, first sentence), resort to domestic lawmaking is a way of crafting a legal framework to ensure compliance of the domestic space activities with the international embedding principles, obligations, and commitments, such safety standards and debris mitigation and prevention.

Also, as states comprise the obligation to authorize, supervise, and control activities of non-governmental entities in outer space (OST, Article VI, second sentence), national regulation is seen as the plausible devised mechanism to regulate individually commercial space activities, inherently risky, pursued by private actors (prescriptive function).

Furthermore, national regulation is drafted to clarify and densify provisions on activities that were not directly addressed in the OST, but do not appear to be explicitly prohibited, and provisions that are vague, imprecise, or very broadly formulated, open to interpretation (interpretative/teleological function).

Finally, enacting special domestic legislation is a strategic tool for securing foreign investments, positioning as an attracting location for launching of space objects, and regulating national space activities2 (strategic function).

National regulation also contributes to a greater legal certainty,3 better predictability, and assessment of risks. Legal certainty and transparency are essential enablers for private investors, insurers, and business rational decisionmaking. As such, the proliferation of regulations governing national activities in outer space is a growing phenomenon, and the number of countries adopting such legal instruments has quadrupled in the last 25 years.

Pursuant to the overarching objective of legal certainty to promote commercial extraction of space resources, some sovereign states have been issuing national legislation on resources use. The 2015 US Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act includes provisions4 establishing a precedent on the commercial exploitation and ownership over space resources extracted by American citizens. The 2017 Luxembourg Law on the Exploration and Use of Space Resources endows companies with property rights to trade and sell mined resources they extract. This law was considered the mechanism to boost the legal confidence of private commercial operators and the first one in Europe covering this domain.

Coming back to recent controversial discussions about asteroid mining, the OST provides for a mere foundational framework for governing space law. It is still fitting and applicable as it intends to maintain the “light touch” and a “non-burdensome regulatory oversight,”5 enabling companies to proceed with their commercial exploitation projects while providing room to mature other conceivable uses. This is why international policy efforts address the current legal uncertainty concerning space resource mining through recent studies, including:

- the 2015 position paper on Space Resource Mining6 issued by the IISL;

- the “Draft Building Blocks for the Development of an International Framework on Space Resource Activities”7 issued by the Hague Space Resources Governance Working Group; and,

- the COPUOS report8 on potential legal models for activities in the exploration, exploitation and utilization of space resources.

| The very vagueness in the drafting of the treaties gives states flexibility while devising national space-dedicated legislation. |

More generally, where new markets emerge, new regulations and laws soon follow. Indeed, the space sector has been marked in recent years by the appearance of a considerable number of different activities no longer falling solely within the scope of space commercial applications. It is a completely new set of activities, all as promising as each other. They offer a new segment of space activities, no more confined to only the Earth-space (launching) or space-Earth segments (telecommunications, imagery, navigation, and weather.) They encompass the space-space segment, which is primarily concerned with in-orbit servicing, reduction of space debris, asteroid mining, and, eventually, tourism, new forms of space transportation, and finally the development of fully private commercial stations that, whether inhabited or not, will provide new services.

These markets are of interest to an increasing number of new players—henceforth, actor—in the space sector, such as NewSpace companies, service providers, agencies, federations, manufacturers, operators, financiers, and insurers, which all call for space regulation.

Modeling space regulations

Remarkably, the Outer Space Treaty contains deliberate omissions with respect to several fundamental issues, including economic exploitation and use of outer space resources. The very vagueness in the drafting of the treaties gives states flexibility while devising national space-dedicated legislation, accomplishing the functions mentioned beforehand. Hence, national space regulations inherit a highly technical burden (coming from the Outer Space Treaty, the Registration Convention, the Liability Convention, and ITU) covering crucial mechanisms and obligations such as registry and licensing, supervision of space activities, mandatory insurance, responsibility, liability, space debris mitigation, and environmental matters.

An analysis of some of the most significant space legislation immediately confirms that what is known as a “spatial law” does not necessarily embody a unified single text of legislative value, as it is for example, the case in France with the LOS (Law on Space Operations, 2008), or the forthcoming laws in Australia or New Zealand.

Conversely, other states choose to adopt a combination of scattered normative texts that do not all enclose the same legal value, operating simultaneously and next to each other. This legal fragmentation or decentralization may be the result, as in the case of the United States, of the accumulation over time of successive texts, each one complementing the other. Ultimately, it may still derive from the fact that the state in question, without belonging to the very exclusive club of space nations, is a user of satellite systems whose interest relies on radiofrequencies, and hence, their space legislation rests on provisions of the law or regulation that sets the frequency regime. Some countries choose to adopt a text by sector of activity, which provides a better readability. Enacted legislation frequently uses the referral technique, i.e., they refer to regulatory texts that must complement the legislative provisions. Further, some countries have made some necessary modifications to existing general laws in order to extend their application to space activities, while still drafting their bill on space activities, as it is the case of India.

| The material scope is closely related to the maturity of the state space industry and the emanations of their private operators. The greater the mastery of space technologies, the wider the field of application. |

In general, the space sector is permeable to the recent observed trend of a new form of normativity, commonly referred to as “soft law.”9 Soft law instruments have become also a form of defining and refining norms for space activities and include, for example, the guidelines of an international organization, codes of conduct for space activities, resolutions, declarations, programs, a technical regulation drawn up by a space agency10 or even standards. Although lacking a binding legal value, soft law instruments shape the operator´s behavior and can be directed towards both states and private actors, for their compliance to best practices determines the granting of a license, or abidance by peer pressure.

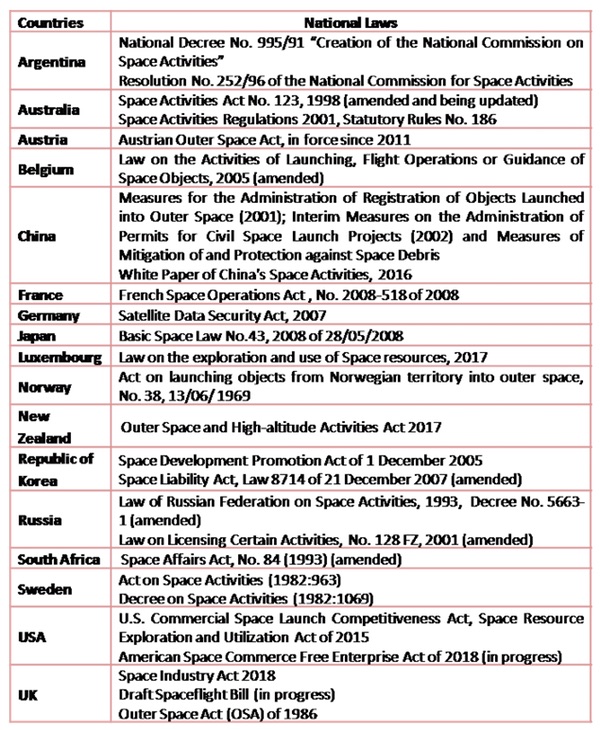

Table 1. Regulations of space activities by state |

Alongside the heterogeneity of forms and contents of national texts—reflecting at the same time the legal traditions of each state, their degree of involvement in the economy of the space sector and, more and more often, their willingness to differentiate themselves from other nations by offering more favorable conditions for space traders (forum shopping)11 —what appears as distinctly striking feature are the convergences that brings them closer together.

These convergences relate to the architecture of the legislation in force, which comprises eight sets of subject provisions, unavoidably regulated in each jurisdiction. These sets include:

- authorization and licensing,

- continuous supervision of non-governmental activity,

- liability and insurance,

- insurance ceiling,

- environmental protection and space debris removal,

- state strategic interest,

- registration process or registry, and,

- transfer of ownership in space or space objects control.

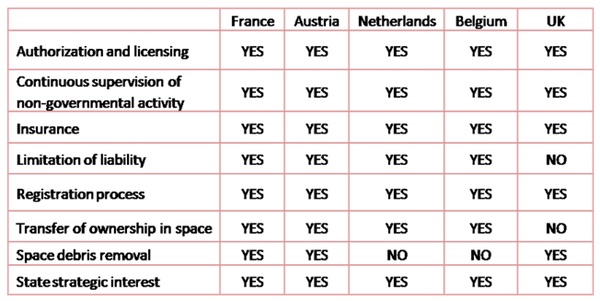

A comparative analysis of space regulations can aid in understanding the similarities and differences between states on these eight legal mechanisms, with the view of detecting common jurisdiction standards. The comparison prevailed over primary and subsidiary legislation, and other government developments, such as the adoption of policy documents and space programs.12 Of the 22 members of the European Space Agency (ESA), only seven members have adopted an internal legal framework governing space operations.13 Except for Norway, the other states have laws regulating all the mechanisms related to space operations. It is noticeable that English law does not provide for limitation of liability of private operators. They incur a priori unlimited liability for damages caused on land or in airspace. The tables below offer a comparative survey within and outside ESA countries.

Table 2. The content of the space laws of the member states of ESA |

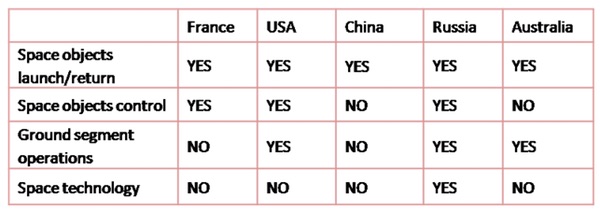

Outside ESA, the states with sufficiently comprehensive space legislation is similar to those in Europe. These laws do not differ significantly in structural terms. The most in-depth legislation belongs to the United States due to its significant involvement in modern space activities, pushing the US government to adopt a large variety of normative texts covering a wider scope of space activities. Following the US example, a reform is underway in most of the spacefaring nations to ease the obligations upon private operators.

Table 3. The content of space laws of States outside the ESA |

Grasping the legislation’s reach

The scope of national legislation sets out the territorial, material, and personal application of the law, i.e. to where the legislation is applicable geographically, to which types of space activities the legislation is applicable, and to whom the legislation is applicable. Therefore, the scope of application is an essential element for any national space legislation.

The definition of the material and personal scope of space legislation is a particularly delicate operation for the concerned states, as well as for other states and their nationals, as a state will exercise any possible jurisdiction concerning particular categories of activities in respect of which it can be held accountable internationally. For the state concerned, it is all about covering the maximum number of operations that could expose it to international liability, in line with the relatively broad definition of the launching state in international treaties. However, under the pretext of protecting their national interests, a state could also seek to attract the operations of nationals of other states.

| Commercial activities are exerting a bottom-up influence in the contemporary lawmaking of states. |

The material scope is closely related to the maturity of the state space industry and the emanations of their private operators. The greater the mastery of space technologies, the wider the field of application. Some states, such as Austria, give their laws a scope that goes beyond the actual level of national activities. In general, the material scope of national laws covers four-fold criterion as depicted in Table 4: the launch of space objects and their return from outer space, space objects control, ground segment operations, and application of space science and technology (Earth observation, space communication, etc.)

Major space powers with proper launch capabilities extend the material scope to launch activities. It must be reminded that a state is considered a launching state if it proceeds or has launched a space object. However, none of the states has transposed this last condition into its legal framework. This leaves a great legal void as to whether the subscription of a launching contract, by a national of a state, engages the latter under the state who has operated the launch. To date, it is therefore difficult to provide a precise answer, as the collision between the satellite of the American company Iridium and a deceased Russian satellite has shown in a recent past. Moreover, UK´s law conveys that the state cannot be regarded as a launching state if its nationals resort to a foreign launch operator.

The majority of space laws apply to control of space objects. Some states, such as Russia or Ukraine, use a very broad definition of space operation. They extend physical competence to the design, testing and use of space technologies.

Table 4. The material scope of space laws |

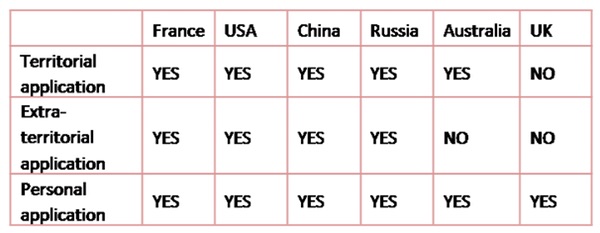

National legislation defines an operating area initially confined to the boundaries of the state’s territory. Treaties require the presence of a link between a state and a space activity. In other words, the state must be able to exercise its full sovereignty over all citizens and assets involved in a space operation occurred in its jurisdiction. Unless expressly authorized by another state, state sovereignty is exercised over the entire territory of the state and over its nationals, natural or legal persons. Hence, the space activities conducted in the national territory or through infrastructure will be considered as national, which fully extends state sovereignty.

Beside the territoriality and extra-territoriality criteria,14 laws also apply to the nationals of the state. The nationality is the jurisdiction link through which a state enforces its legislation upon activities undertaken by its nationals. The major space powers jointly use the three-fold criteria to have a greater number of cases subsumed to their national legal framework. Other states choose to use only certain connecting criteria. The UK´s Space Operations Act applies only to its nationals and hence the criterion of territoriality is not foreseen.

This analysis reveals that space laws have an extremely wide field of application, which target a very large number of hypotheses. A state shall authorize and control an activity on which it has originally exercised state sovereignty. However, states changed this restrictive conception. In the hypothesis of a cross-border space activity, all the involved states are implicated in this activity, but they are only involved to the extent of the level of their national activity. In fact, the states extend their jurisdiction over the whole activity.

In general, space laws do not define the intensity of the connection that must exist between an activity and the state, so that the latter becomes empowered to control it. The personal and territorial scope of national space laws are shown in Table 5.

Table 5. The personal scope of space laws |

Racing with space activities

Commercial activities are exerting a bottom-up influence in the contemporary lawmaking of states. A convergent regulatory policy is thus currently being set, both at a national and global level, as states adopt national space legislation in connection with the activities they are and will be engaged with. Recent examples include the New Zealand Outer Space and High-altitude Activities Act, 2017; suborbital flights (UK Draft Spaceflight Bill, 2017; draft of the American Space Commerce Free Enterprise Act, H.R. 2809, 2017); the regulation of nanosatellites (Netherlands Unguided Satellites Decree); mega-constellations; space mining (with the recent business-friendly laws on space resource mining from the US and Luxembourg); and space travel and tourism (the UK Space Industry Bill 2018).

For now, domestic legal frameworks regulate prospectively the most imminent practices until commercial projects like space tourism and mining operations begin, and if commercial interests can continue to foster and engage the national governments to act and be involved within space activities, the space race can continue.

In the future, enacting modern national space law needs to keep up with a dynamic reviewing process to avoid the potential risk of being out of date at an accelerating rate and becoming obsolete. This risk suggests the fallibility of regulating too far in advance and thus lacking on practical experience. In fact, space-related technologies at the service of NewSpace commercial activities are changing and evolving over a relatively short timeframe, demanding an ongoing review of the issued domestic legal norms. Consequently, either within the initial drafting, or in the subsequent review process, it is desirable to balance “the need for regulation of the economic and technical elements, so as to minimize the risks to an acceptable level, and the facilitation of research and innovation to allow for greater and more efficient access to space, and the potential for commercial returns, on the other.”15

What industry envisions is an adaptive, light, and relatively permissive rulemaking process that would further enable the rapid efficient and predictable permitting of commercial activities. The financiers and entrepreneurs behind these operations wish for assurances that regulations will not stifle the nascent industry: “What the space industry wants is regulatory certainty without regulatory burdens that are going to strangle innovation.”16

| What industry envisions is an adaptive, light, and relatively permissive rulemaking process that would further enable the rapid efficient and predictable permitting of commercial activities. |

How, then, is it possible for legislation to keep up with space activities? There are three possible venues: the principle of adaptive governance ,17 the “Telecommunications Packages” instance, and the mechanism of interdependency of regulatory policies. The principle of adaptive governance means that space activities should be incrementally regulated at the appropriate time on the basis of contemporary technology and practices, instead of attempting comprehensive regulation, thus promoting consistency and predictability among domestic frameworks of states.

Governments could hold on the example of the moratorium of Telecommunications Packages to adjust the regulatory framework to the market dynamics. The proposal seeks to make the access rules more focused and legally certain. It limits the conditions under which market access obligations can be imposed (only to address the shortcomings of markets) and gives regulators the possibility to review markets every five years (currently every three years). See the Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing the European electronic communications code.18

Finally, it could be worth to point out that regulatory policies of countries are interdependent19 in three modes: the competitive, the coordinative, and the informational. Bearing that in mind, a government could act in furtherance of a coherent regulatory framework and maintain the race between regulations and space activities. In the competitive mode, policymakers attempt to have distinctive policies that provide some advantage, ensuring their domestic industry’s competitiveness over other countries. In the coordinative mode, there is a tenable advantage for all countries to adopt the same policy. Coordination plays in pushing jurisdictions to have compatible adherent converging rules or standards, which is best for all. In the informational mode, the choices and experiences of countries produce informational externalities, pointing the way for other countries for regulatory decisions and convergence.

The homogeneity of regulations between countries would provide a repertoire for future policy responses among jurisdictions. In this view, the SIRIUS SpaceLegalTech Observatory will soon reflect the upcoming legal changes, offering new opportunities for comparative studies to space lawmakers in a changing international context, now dominated by the states and which, because of the magnitude of the upheavals that affect it, calls for global space governance.

Endnotes

- We understand “regulation” in a broad comprehensive sense, referring to the setting of norms that govern conduct by public and/or private actors, whereas “legislation” connotes legally binding and enforceable legislation promulgated by a legislative authority.

- Fabio Tronchetti, “The Future Challenges of Space Law and Policy”. In: Fundamentals of Space Law and Policy. SpringerBriefs in Space Development. Springer, New York, p. 83, 2013.

- “(…) Space law is therefore made more certain by the intelligent adoption of appropriate national provisions”, Francis Lyall, Paul B. Larsen, “Space Law: A Treatise”, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., p. 37, 2009.

- The two most relevant sections: (Sec. 402) “facilitate the commercial exploration for and commercial recovery of space resources by US citizens; discourage government barriers to the development of economically viable, safe, and stable industries for the commercial exploration for and commercial recovery of space resources in manners consistent with US international obligations; and promote the right of US citizens to engage in commercial exploration for and commercial recovery of space resources free from harmful interference, in accordance with such obligations and subject to authorization and continuing supervision by the federal government. A US citizen engaged in commercial recovery of an asteroid resource or a space resource shall be entitled to any asteroid resource or space resource obtained, including to possess, own, transport, use, and sell it according to applicable law, including US international obligations. (Sec. 403)(…) United States does not, by enactment of this Act, assert sovereignty or sovereign or exclusive rights or jurisdiction over, or ownership of, any celestial body”.

- Cristin Finnigan, “Why the Outer Space Treaty remains valid and relevant in the modern world”, The Space Review, 2018, accessed on 14/06/2018.

- See this link.

- See this link.

- See this link

- Irmgard Marboe, (Ed.) “Soft Law in Outer Space. The Function of Non-binding Norms in International Space Law”, Wien, Köln, Weimar: BöhlauVerlag, 2012.

- Space agencies also have regulatory power; it is noteworthy that both Argentina and Brazil’s space agencies regulate their space operations by issuing regulations. They are also thinking of using a legislative mechanism to adapt to new realities.

- Fabio Tronchetti, “The Future Challenges of Space Law and Policy. In: Fundamentals of Space Law and Policy, SpringerBriefs in Space Development. Springer, New York, p.83, 2013.

- Although some states appear rather inactive presently, it is worthwhile to keep them on our radar for any future evolution.

- For the moment, Germany has limited itself to a system that only controls the dissemination of data obtained by remote sensing.

- “Quasi-territorial” jurisdiction is available for space objects registered within a certain state.

- Steven Freeland, Kirsty Hutchison, Val Sim, “How Technology Drives Space Law Down Under: The Australian and New Zealand Experience”, vol. 43 Air and Space Law, Issue 2, pp. 129–147, 2018.

- Jason Krause, “The Outer Space Treaty turns 50: can it survive a new space race?” ABA Journal. 103.4, 2017, retrieved on 14/06/2018.

- See this link

- See this link

- David Lazer, “Global and Domestic Governance: Modes of Interdependence in Regulatory Policymaking”, European Law Journal, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 455-468, 2006.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.