British launch plans finally lift offby Jeff Foust

|

| “In terms of civil engineering, this is not overly complex,” said Kirk of the planned launch site. “It’s not Cape Canaveral.” |

Less than 24 hours after the World Cup ended in Moscow, the British space industry got a double dose of good news. The British government, through the UK Space Agency, announced the long-awaited selection of a launch site in the country, followed by the selection of two companies that will receive funding to support operations there. The selection brought to an end a years-long effort to support a launch industry in the country, one that evolved from suborbital spacecraft taking off from airports to small launch vehicles tapping into the growing interest in smallsats.

The British government took an unusual two-step approach to the announcements, made just as the Farnborough International Airshow was getting underway outside London. The first announcement, made late July 15, formally selected a site in Sutherland, in northern Scotland, as the location of the country’s first orbital launch site.

The site in question would host small, vertically launched orbital rockets. Launching to the north, such launches could support payloads going to Sun-synchronous and other high-inclination orbits, with limited downrange concerns, as well as easier access to airspace.

Leading development of the Sutherland launch site will be the Highlands and Islands Enterprise, an economic development agency, which received £2.5 million (US$3.3 million) to start work on the facility.

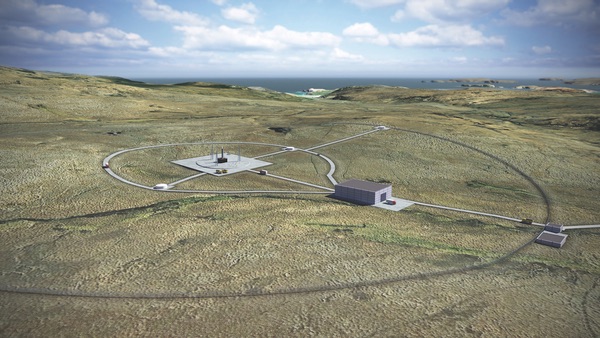

Illustrations of the site show a simple pad with limited infrastructure, similar to other facilities developed in recent years for small launchers, like Rocket Lab’s site in New Zealand. “In terms of civil engineering, this is not overly complex,” said Roy Kirk, the spaceport project manager for Highlands and Islands Enterprise. “It’s not Cape Canaveral.”

An illustration of the planned UK spaceport in Sutherland, Scotland. (credit: Perfect Circle PV) |

The design of the facility, he suggested, is secondary to dealing with public relations and regulatory issues for the site. Public outreach efforts are planned to convince local residents of the limited risks of the launch site and the economic benefits, such as the creation of several hundred highly skilled jobs.

| “We just announced yesterday, so there are a lot of details to fill in,” said Ambrose of Lockheed’s launch plans. “Now that we have announced, we can go ahead and go finish up a lot of our deliberations.” |

Planning for the facility has quietly been in progress for some time, Kirk said, including discussions with Scottish national heritage and environmental agencies. “There are undoubtedly challenges in the planning process, as there is for any project,” he said. “The critical thing here is to understand what are the issues, what are the opportunities, what’s the local feeling.”

The government waited until the next morning, though, to announce who would be the first to launch from Sutherland. The UK Space Agency said that it was providing $31 million to Lockheed Martin, the American aerospace and defense giant, and $7 million to Orbex, a British-headquartered startup, to use the site for launches of small vehicles.

“The countdown to the first orbital rocket launch from UK soil has officially begun,” said Patrick Wood, Lockheed Martin’s UK country executive for space, in a statement. But beyond the fact that both companies planned to use the Sutherland site for small launch vehicles, the two had little in common.

In the case of Lockheed Martin, the company was not developing its own launch vehicle. The money would go towards establishing launch operations at Sutherland, as well as developing an upper stage called the Small Launch Orbital Maneuvering Vehicle that will be built by Moog in the UK, as well as a technology demonstration cubesat built in cooperation with Orbital Micro Systems, a startup planning a fleet of such satellites to collect weather data.

In the days leading up to the announcement, the rumor was that Lockheed Martin would partner with Rocket Lab to use that company’s Electron rocket from Scotland. Lockheed Martin made a “strategic investment” in Rocket Lab in 2015, and Electron would be the right fit for a spaceport like Sutherland.

However, Lockheed Martin declined to confirm that the Rocket Lab was the company they were working with, not disclosing the vehicle it planned to use. Illustrations released by the company showed a vehicle that looked superficially like the Electron, including its distinctive black paint job, but the rocket shown looked more generic than the Electron and sported only the Lockheed Martin logo and the Union Jack.

At a Lockheed Martin briefing during the Farnborough air show last week, company officials strongly suggested that they planned to use Electron, but declined to commit to it when asked directly about it. “We just announced yesterday, so there are a lot of details to fill in,” said Rick Ambrose, executive vice president of Lockheed Martin’s space business. “Now that we have announced, we can go ahead and go finish up a lot of our deliberations.”

“We’ve worked very close with that particular organization. We understand their launch vehicle very well,” Wood said. “We are a strategic investor in Rocket Lab and that’s where we’re focusing at the moment.”

They even appeared to leave the door open to using a different launcher. “We’re working across all of our supply chains,” Ambrose said. “We have a lot of details to work out across the board.”

In the case of Orbex, it’s very clear what vehicle they will use: their own Prime vehicle under development. It’s intended to be similar in performance to Electron, able to place about 150 kilograms into a standard Sun-synchronous orbit.

An illustration of Orbex’s Prime launch vehicle lifting off from Scotland. (credit: Orbex) |

One aspect of Prime’s design that sets it apart from other vehicles is the use of an uncommon fuel: propane or, more specifically, bio-propane, which is made from renewable biomass and has a carbon footprint of about one tenth that of kerosene. It has the advantage of remaining liquid at the cryogenic temperatures of its oxidizer, liquid oxygen.

That, in turn, simplifies vehicle design, said Orbex CEO Chris Larmour. The vehicle uses a “coaxial tank” design where a central tube of propane is surrounded by an outer tank of liquid oxygen, resulting in structural mass savings. He added propane also has a slightly higher specific impulse than kerosene: a good combination for a small launch vehicle, he argued.

“The entire vehicle has been built around that core starting decision,” he said. “That fuel drives a lot of benefits for a small launcher. It’s kind of overlooked.”

| “There are a lot of competitors in the United States of America,” said Larmour. “We’re happy for them to compete with each other, and we’ll focus on Europe.” |

At the same time the UK Space Agency announced funding for Orbex, the company announced it had raised about $40 million for its launch vehicle effort. That total included the UK government funding as well as other grants from ESA and the European Commission, as well as private investment from venture funds and Spanish technology company Elecnor Deimos.

That funding is more than half of the $70–75 million Larmour estimated it would take to get to the first launch of Prime. “It gets us a good way along the track to first launch,” he said.

It also means, he believed, that Orbex—operating largely in stealth mode prior to now—should be taken seriously amid the dozens of efforts around the world developing small launch vehicles, with varying levels of technical achievement and financial backing.

“There are about 80 projects out there talking about building a small launcher,” he said. “But when you filter them on who has assets to do something, who has experience and understanding of the problem, who’s making progress, it’s a much smaller number: a handful of companies. I think Orbex, with this announcement, has joined that family.”

Orbex also plans to stand out by not competing head-to-head with many of the American-based small launch vehicle ventures, instead focusing on European companies that may find it easier to launch on a European vehicle from Europe rather than exporting their satellites to the US or other countries. (Britain’s impending exit from the EU could complicate that, he acknowledged, but added that the company, which has subsidiaries in Denmark and Germany, is also considering a second launch site, possibly in the Azores.)

“There’s willingness to look at solutions that are a little bit easier to access in time and space, and the price point may not be as sensitive an issue,” he said of European launch customers. “There are a lot of competitors in the United States of America. We’re happy for them to compete with each other, and we’ll focus on Europe.”

One challenge for Lockheed Martin and Orbex to share the same launch site is the differences in their vehicles: Electron uses RP-1, the rocket-grade version of kerosene, as fuel, while Prime uses propane. Larmour said there may end up being two separate launch pads at the site with vehicle-specific utilities, but sharing the same general infrastructure, from security to range management.

“We’ll spend the next few months talking to all kinds of stakeholders involved,” he said. “Where it’s helpful to work in common, we’ll do it.”

The overall effort has what officials acknowledge is an ambitious schedule: completing the launch site in 2020 and supporting first launches from there in 2021. “There is a slight time pressure on this,” Kirk said. “I think we’re all aware of that.”

Besides the spaceport construction, the UK government needs to develop regulations for licensing such launches, building on legislation approved earlier this year. “From our point of view we’re comfortable with a 2020 schedule,” Wood said. “We understand it’s challenging, and our job is to really support the UK Space Agency on how to support that regulatory framework.”

Larmour said that, for now, development of Orbex’s launch vehicle and development of the spaceport are neck-and-neck for being in the critical path for supporting a first launch in 2021, a timeline he said assumes the launch site it completed in 2020.

| “This is a business,” Kirk said. “There are three reasons this will work, and it’s money, money, and money.” |

While there are regulatory and technical risks, they are not necessarily the biggest ones. Building a launch site is not, as Kirk mentioned, a major civil engineering feat, with the bigger hurdle being winning the necessarily environmental approval and other permits and winning the support of local residents. And, with the large number of small launch vehicles in development, there may be options for other users should Lockheed Martin and Orbex both fall through for some reason.

The biggest one is whether the spaceport makes sense economically: can it win business, in the form of launches by Lockheed Martin and Orbex, and possibly others, given all the competition from launch sites and launch systems around the world? Kirk stressed the economics of the site in his comments at a Lockheed Martin briefing about its launch plans.

“We believe the site can make money but also offer a really competitive rate for the launch service providers,” he said. “This is not going to be an expensive option. If we do that, we will have failed.”

“This is a business. There are three reasons this will work, and it’s money, money, and money. The state will pump-prime it, but after that it’s got to make money.”

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.