Reviews: Brief Answers to the Big Questions and On the Futureby Jeff Foust

|

| And why leave Earth? “The obvious answer is because it’s there, all around us,” Hawking argues. “Not to leave planet Earth would be like castaways on a desert island not trying to escape.” |

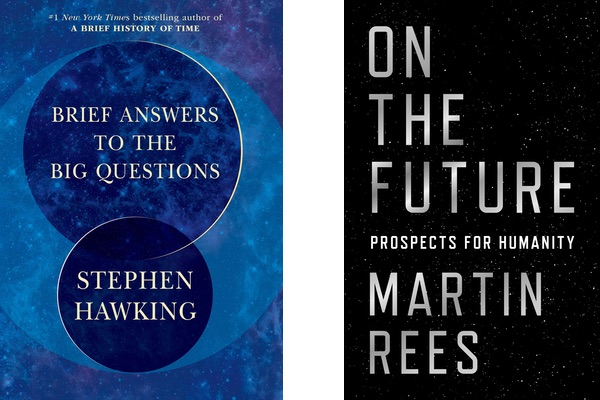

Both Hawking and Rees have recently published new books that discuss issues far afield from astrophysics. (Hawking was working on his book at the time of his death; the publisher notes that it was completed “in collaboration with his academic colleagues, his family and the Stephen Hawking Estate.”) Both cover a wide range of topics, extending far beyond the origin and the fate of the universe. However, in the case of spaceflight, an issue both discuss, their thoughts are not particularly novel.

In Brief Answers to the Big Questions, Hawking frequently harkens back to the early days of the Space Age, which he sees as a golden era without mentioning the geopolitical roots that drove those early accomplishments. “To leave Earth demands a concerted global approach—everyone should join in,” he writes. “We need to rekindle the excitement of the early days of space travel in the 1960s.”

And why leave Earth? “The obvious answer is because it’s there, all around us,” he argues. “Not to leave planet Earth would be like castaways on a desert island not trying to escape.” Except, of course that, despite all its problems, that desert island appears to be far more hospitable than other islands far away across the sea. “It won’t solve any of our immediate problems on planet Earth, but it will give us a new perspective on them and cause us to look outwards rather than inwards.”

He supports human missions to the Moon and Mars, at one point calling for a base on the Moon by 2050 and a “manned landing on Mars by 2070,” deadlines that don’t seem to offer much in the way of urgency and excitement. (Both Hawking and Rees refer to “manned” spaceflight rather than the more inclusive “human” or “crewed.”) Such goals “would reignite the space programme, and give it a sense of purpose, in the same way that President Kennedy’s Moon target did in the 1960s.”

| “The practical case for manned spaceflight gets weaker with each advance in robots and miniaturisation,” Rees concludes. |

Rees, like Hawking, was inspired by the early Space Age and seeks to recapture it in some way. “If there were a revival of the ‘Apollo spirit’ and a renewed urge to build on its legacy, a permanently manned lunar base would be a credible next step,” he writes. But, as he has argued in the past, he’s not fond of governments doing such missions—or, at least, NASA. “If I were an American, I would not support NASA’s manned programme—I would argue that inspirationally led private companies should ‘front’ all manned missions as cut-price high-risk ventures.” (He does give an exception to China, believing that country will seek “footprints on Mars” as a way of demonstrating its superiority over the US.)

To Rees, human spaceflight is primarily for adventure, hence his desire to have the private sector take the lead. “The practical case for manned spaceflight gets weaker with each advance in robots and miniaturisation,” he concludes after recounting the achievements of robotic spacecraft, from large space observatories to the fleet of Earth imaging cubesats operated by Planet. He said he thinks humans will establish bases on Mars by 2100, but argues against large-scale space settlement; it’s not clear, then, what the people on Mars at the end of the century will be doing beyond, well, adventuring.

Spaceflight is just a small part of each book. Rees devotes far more attention to climate change, artificial intelligence, and biotechnology in his book. Hawking’s book lives up to its title: chapter titles include “Is There a God?”, “How Did It All Begin?”, and “Is There Other Intelligent Life in the Universe?”—and those are just the first three chapters.

In the end, neither Hawking nor Rees break much new ground about, or offer strong arguments for, human spaceflight. The two have different approaches—Hawking with his “concerted global approach” and Rees with his reliance on the private sector—but neither man proposes much in the way for rationales for doing so, beyond adventure and “because it’s there,” arguments that have in the past been insufficient for most governments and private investors.

Rees, in that passage in his book about the perils of aging scientists moving outside their disciplines, says that scientists “need continually to absorb new concepts and new techniques if they want to stay at the frontier—and that’s what gets harder as we get older.” In spaceflight, there’s certainly a need for new concepts and new techniques, and new rationales, that perhaps only the next generation of scientists, engineers, and others can provide.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.