Three ways to the Moonby Jeff Foust

|

| “They are becoming part of the catalog,” Zurbuchen said of the winning CLPS companies. “They will compete for tasks that we’re going to put out there weeks and months from now.” |

And that was indeed what NASA announced Thursday, although it could be hard at times to figure that out during the hour-long event. Students from local FIRST Robotics teams got to show off their projects, then pepper NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine and Thomas Zurbuchen, the associate administrator for science, with questions. The event shifted for a time to the Johnson Space Center in Houston, where astronaut Stanley Love bounded across a floor in a harness intended to simulate the Moon’s one-sixth gravity. Eventually, halfway into the event, there was an opportunity for reporters in the room and on the phone to ask questions, interspersed with more questions from students in the room and from social media.

There was, also, the announcement itself: NASA selected nine companies for its CLPS program, making them eligible for future awards to deliver NASA payloads to the lunar surface. Representatives from the companies walked up on stage, shook hands with Bridenstine, posed for pictures… and then walked off stage, seen but not heard. “What an odd event,” a representative of one of the companies said afterwards.

While NASA played up the fact that the contracts are worth up to a combined $2.6 billion over ten years, the winning companies only got small amounts of NASA funding to develop payload users’ guides. Those companies will have to compete at a later date for task orders under those contracts to deliver payloads to the Moon, with no guarantee that any of the companies will win anything.

“They are becoming part of the catalog,” Zurbuchen said. “They will compete for tasks that we’re going to put out there weeks and months from now.” NASA suggested those missions could start flying as soon as next year, but most industry observers don’t expect the first mission with a CLPS payload to fly until 2020, given the state of development of the landers. NASA has yet to identify any specific payloads it wants to fly on those missions, beyond small laser retroreflectors.

The nine winners can be split into four categories. One category consists of three companies long considered frontrunners for CLPS: Astrobotic, Masten Space Systems, and Moon Express. The three had been part of NASA’s Lunar Cargo Transportation and Landing by Soft Touchdown (CATALYST) program, where the agency provided technical support. Astrobotic and Moon Express were also former competitors in the now-defunct Google Lunar X Prize (GLXP), while Masten had shown an interest in lunar landers for years, including winning more than $1 million in the Northrop Grumman Lunar Lander Challenge in 2009, part of NASA’s Centennial Challenges program.

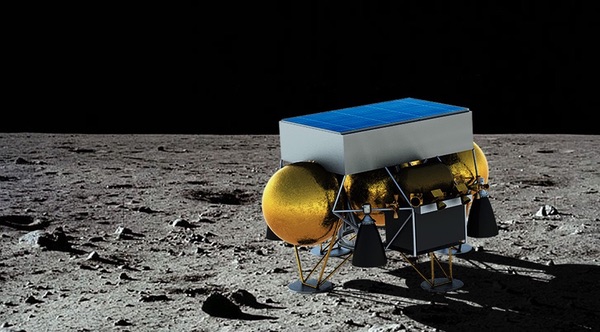

Astrobotic and Moon Express are continuing development of previously announced lunar landers, while Masten said it’s developing XL-1, a lander capable of placing 100 kilograms on the lunar surface. “We are eager to apply our capability-driven approach refined over the last decade as we go to the lunar surface,” said Masten CEO Sean Mahoney.

A second group consists of companies that teamed with foreign competitors for the GLXP. (NASA’s required that, under CLPS, the prime contractors be US companies, with the assembly and integration of spacecraft done inside the US.) Draper, one of the CLPS winners, announced in October that its team included Japan’s ispace, which competed as Team Hakuto for the GLXP and is now developing its own lunar landers.

Orbit Beyond a New Jersey-based company, is working with India’s Team Indus, which has continued to work on lunar lander designs after the end of GLXP. “The design is really mature now,” Jeff Patton, chief engineering advisor for Orbit Beyond, said of Team Indus’ design.

One company stands out in a group of its own: Lockheed Martin, the only large aerospace company to win a CLPS award. Lockheed said it will offer NASA the McCandless Lunar Lander, named after the late astronaut Bruce McCandless and based on the designs the company has developed for Mars missions such as the just-landed InSight spacecraft.

| “Think of it like venture capital. Our investment is low because we have other people who are investing,” said Bridenstine. |

“Lockheed Martin has built more interplanetary spacecraft than all other US companies combined, including four successful Mars landers,” Lisa Callahan, vice president and general manager for commercial civil space at Lockheed Martin, said in a statement. “We can maximize the value of CLPS for lunar science operations as well as the path forward to tomorrow’s reusable human lander.”

The remaining three are a miscellaneous lot. Deep Space Systems is a small Colorado company that has primarily worked in systems engineering for various spacecraft. Firefly Aerospace is a launch vehicle developer that promises an “integrated lunar surfaces offering” with its lander launched on the company’s planned Beta rocket. Intuitive Machines is an engineering company that developing a lander using technology from NASA’s Project Morpheus. (Intuitive Machines is working with other companies, like Firefly; it previously worked with Moon Express but that arrangement fell apart, leading to lawsuits that Intuitive Machines have won, pending appeal.)

Bridenstine implicitly acknowledged that many of these companies may never fly their landers because of technical or financial issues. Many of these companies still have to raise significant amounts of funding for their landers, which in most cases are not beyond the critical design review level of maturity. Even a company like Lockheed Martin, with the technical and financial resources in house to do lunar landers, still has to decide if it’s worthwhile.

“Think of it like venture capital. Our investment is low because we have other people who are investing,” said Bridenstine. “But we have more providers. In other words, the portfolio is larger, so we can take risk.”

Representatives of the nine companies that won CLPS awards stand with NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine (far left) and NASA associate administrator for science Thomas Zurbuchen (far right) at NASA Headquarters last week. (credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls) |

Larger and larger landers

It’s likely that a CLPS lander will be the next American spacecraft to make a soft landing on the Moon, be it in 2019, 2020, or later. But NASA is looking ahead to future, larger spacecraft it expects to need in the next decade to implement Space Policy Directive 1, the year-old space policy that directs NASA to lead a sustainable human return to the Moon.

A next step up from CLPS is a “mid-sized” lander capable of placing 300 to 500 kilograms on the lunar surface. That would enable more ambitious science missions and feature capabilities such as direct-to-Earth communications, a lifetime on the surface of months and the ability to deliver, and later recharge, small rovers, said Steve Clarke, deputy associate administrator for exploration in NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, during a meeting last month of the Lunar Exploration Analysis Group (LEAG).

| A fully-fueled single-stage lander, like that proposed by Lockheed, would be so heavy that it would be difficult to transport to the Moon, NASA argued. |

Many of the details about how those landers will be developed have yet to be determined, though. “We’re in the process of looking at all the various trade options that we have as we build up this strategy,” Clarke said. NASA does have a goal of flying the first of those mid-sized landers in 2022, which means those details will need to take shape soon. “I hope to be able to talk more about this as we develop this and narrow down some of the trade spaces.”

Beyond the mid-sized landers are larger “human-scale” or “human-class” landers that, as the name suggests, would be able to carry people. Studies of those landers are just beginning, but industry hasn’t been shy to provide their own ideas.

Lockheed Martin, for example, unveiled its concept for a crewed lunar lander in October. It offered a giant, single-stage vehicle leveraging Orion technology as well as earlier work on Mars landers, and capable of supporting a four-person crew on the lunar surface for two weeks.

The Lockheed concept would weigh 62 metric tons when fully fueled with liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen, but 22 tons when empty. Lockheed offered a vision for the lander where it could be launched empty and they fueled at a propellant depot in lunar orbit, perhaps in the same orbit as the lunar Gateway, with that propellant eventually coming from lunar resources.

NASA, though, is leaning away from such large landers. A fully-fueled single-stage lander would be so heavy that it would be difficult to transport to the Moon, argued Jason Crusan, head of NASA’s Advanced Exploration Systems division, at the LEAG meeting. “They’re actually in excess of what our SLS is capable of,” he said.

Crusan said that NASA has also looked at two-stage landers, with ascent and descent stages. The mass of the descent stage in particular—which he estimated to be 32–38 metric tons—would still be so heavy as to limit launch options, he concluded.

What NASA appears to favor, though, is a three-stage approach, which includes a tug along with ascent and descent stages. “What’s interesting about this is that your per-element mass drops to 12 to 15 metric tons,” Crusan said. That enables each stage to be transported on a number of different launch vehicles as well as be co-manifested on SLS missions, in much the same way much of the Gateway will be transported to lunar orbit.

Crusan noted that NASA had planned to solicit concepts for lunar landers over the summer, then put that on hold. That will be reopened by the end of the year to get industry ideas on human-class lunar landers.

NASA’s goal is to be able to test the descent stage of that human-class lunar lander as a standalone mission in 2024. That approach would allow a full-scale lander, with people on board, make a lunar landing in 2028.

| “This comes across as having no sense of urgency,” said Schmitt of NASA’s plans to return to the Moon. |

That approach depends on the funding the agency receives in fiscal year 2019—the agency is still operating under a continuing resolution funding the agency at 2018 levels even though the new fiscal year started two month ago—and beyond. “This is all budget dependent,” said Tom Cremins, NASA associate administrator for strategy and plans, at a meeting of the National Space Council’s Users’ Advisory Group (UAG) last month. “This is notional planning.”

Cremins got pushback from UAG members at that meeting, not because of the specifics of lunar lander development but rather because of the pace of the program. “This comes across as having no sense of urgency,” said Apollo 17 astronaut Harrison Schmitt. “I think there should be a sense of urgency.”

“Personally, I think 2028 for humans on the moon, that’s ten years from now. It just seems like it’s so far off,” said another former astronaut, Eileen Collins. “We can do it sooner.”

That criticism is focused more on the development of the Gateway as an intermediate step towards the lunar surface than any questions about NASA’s lunar lander plans. Later in the UAG meeting, former NASA administrator Mike Griffin, now undersecretary of defense for research and engineering, weighed in on NASA’s lunar plans, calling a 2028 human return “so late to need as not even to be worthy of being on the table” and the Gateway a “stupid architecture.”

How those lander plans would change in the absence of the Gateway isn’t clear. Bridenstine has frequently likened it to Apollo’s command and service modules, providing an infrastructure around the Moon to support operations on the surface, be it crewed missions or teleoperated rovers.

But when those plans for larger lunar landers are eventually sorted out, with or without the presence of a Gateway supporting them, perhaps NASA can hold a more conventional briefing to describe them.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.