Forces of darkness and lightHow fears of resource depletion and nuclear war influenced American space policy during the 1970s and 80sby Dwayne A. Day

|

| “The perceived threat to human survival galvanized a group of technological optimists to propose outer space not only as a solution to the Malthusian crisis of overpopulation, energy depletion and environmental damage, but also to the possibility of nuclear Armageddon.” |

But by June 1979, Keith Henson had abandoned his ambivalence, stating that the military could fund mass drivers and solar sails, which could be used to deliver asteroids to Earth orbit, where they could serve as “space forts” equipped with lasers and particle beams. Henson then wrote several more articles embracing this idea of using military funding to support space settlement.

In a 1981 article titled “Lase the nukes,” Carolyn Henson endorsed the idea of space-based lasers for defeating ballistic missiles. Her argument was that they were “surgical” and “elegant,” and they promised a solution to the threat of nuclear war. Carolyn also remarked on the irony that an anti-war protestor had now become a space-laser supporter.

Westwick makes several very insightful observations about the L5 Society and the Strategic Defense Initiative. The first is that L5 provided an optimistic vision of space as the solution to resource depletion and space as a solution to the threat of nuclear annihilation. His other observation is that the link between space militarization and space development shifted several times among the space development advocates. Some saw space militarization as the inevitable outcome of space development, whereas others—and sometimes the same people—saw space militarization as a means to achieve their ends of developing space, not an end goal. Finally, Westwick noted that this was an odd development where people on the far-left and the right could end up supporting the same idea of space-based missile defense, in large part because it seemed like a good, if not the only, solution to break out of the straightjacket of Mutual Assured Destruction.

Other L5 Society members also saw a connection between space capabilities and tackling the threat of nuclear war. Lowell Wood, a protégé of hydrogen bomb inventor Edward Teller, was working at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in “O Group,” which developed advanced weapons concepts. One of the ideas that came out of O Group was the X-ray laser that theoretically could use a nuclear explosion to create multiple beams that could destroy many missiles in flight near-instantaneously. There were other O Group members who were also enthusiastic about space and were or had been members of the L5 Society, including Stewart Nozette, who had obtained a Ph.D. in planetary science from MIT and had written articles for L5 News and Future Life about possible asteroid mining missions. Nozette claimed that these missions could avoid gloomy scenarios for humanity’s future. Many years later, Nozette was the program manager for the Strategic Defense Initiative-funded Clementine mission that tested missile detection sensors while also searching for resources on the Moon. (Nozette was smart, but not bright—he is currently serving time in federal prison for selling classified satellite information to an undercover FBI agent who he believed worked for the Israeli Mossad intelligence service.)

| Some saw space militarization as the inevitable outcome of space development, whereas others—and sometimes the same people—saw space militarization as a means to achieve their ends of developing space. |

Herman Kahn, whose 1960 book On Thermonuclear War helped secure his reputation as a cold-hearted nuclear theorist and inspired the character of Dr. Strangelove in the Kubrick film, was also interested in using space resources to solve problems on Earth. In 1976 he wrote to California governor Jerry Brown, and then visited the governor to discuss such topics in a meeting that received considerable publicity. Brown had been a technological sceptic, embracing “appropriate technology” for social problems. Kahn’s influence on Brown is hard to discern, but soon after the meeting Brown was speaking of an “era of possibilities,” whereas earlier he had spoken of an “era of limits.”

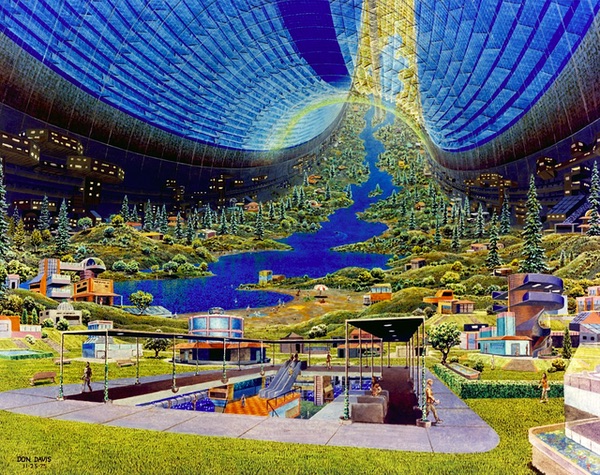

Space-based missile defense concepts from the 1980s, including lasers, has links to the space colony visions espoused in the 1970s. (credit: Lockheed) |

From science fiction to the White House

Science fiction author Jerry Pournelle wrote A Step Farther Out in 1979 as a response to the Club of Rome report. After Ronald Reagan’s election in November 1980, Pournelle, with support from the L5 Society and the American Astronautical Society, formed the “Citizens Advisory Council on National Space Policy.” It had approximately 50 members, including science fiction authors Robert Heinlein and Poul Anderson, and astronauts Wally Schirra and Gordon Cooper. Shortly after Reagan’s inauguration, 30 members of the Council met one weekend at the end of January 1981 at the home of Pournelle’s frequent co-author Larry Niven. They produced a report in spring 1981 titled “Space: The Crucial Frontier” that advocated space as the solution to many of America’s problems, including the threat of nuclear war.

Pournelle claimed that the Council had direct access to Reagan’s national security adviser Richard Allen, who reportedly transmitted the Council’s report to Reagan. In March 1983, Reagan gave a speech announcing the creation of the Strategic Defense Initiative which would seek to use space-based weapons to “make nuclear weapons obsolete.” Robert Heinlein later claimed that the Council’s report led directly to Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative speech in 1983.

In 1999, science fiction author Norman Spinrad wrote about the Council’s influence on Reagan’s space policy and, according to Westwick, “reintroduced the old coat-tails argument” from the 1970s. Spinrad gave Pournelle credit for supporting SDI as a way to attain long-range space development, an argument that Keith Henson had first made in the latter 1970s. As Westwick notes, Spinrad’s claim put a new twist on SDI: some Reagan advisers believed (or claimed after the fact) that SDI was a way to force the Soviets to spend themselves into bankruptcy, but Spinrad’s version was that SDI was an effort to get the American military to spend money “on a chimerical military program that would eventually help humanity populate outer space.” Westwick adds, however, that Pournelle was an avowed anti-communist, so while he might have been deceiving the military about his group’s ultimate goals, he may also have believed that SDI was the right thing to do from the standpoint of national defense.

The fertile ground of the Cold War stalemate

While Jerry Pournelle’s friends liked to credit him and the Council with directly influencing the creation of the Strategic Defense Initiative, the historical record is far murkier. Missile defense had been around for decades, dating back to World War II and the V-2 rocket. Whereas the United States had enjoyed a substantial ballistic missile advantage over the Soviet Union during the 1960s, that advantage had eroded by the 1970s and there was increasing concern about the vulnerability of America’s strategic nuclear arsenal, prompting new ideas about how to protect it. As Steven Pomeroy wrote in his 2016 book An Untaken Road, throughout the 1970s there were numerous proposals for changing the deployment of nuclear weapons to avoid their destruction by Soviet weapons. To some extent, this fertile discussion ground had inspired Keith and Carolyn Henson.

| Westwick claims that SDI and missile defense had a lasting influence on American space policy. Reusable launch vehicles, inflatable spacecraft, and infrared astronomy did not originate as ideas in the SDI program, but they certainly gained momentum from it. |

As Westwick explains, one of the unique values of the space settlement movement of the 1970s may have been its inherent idealism. The L5 Society “injected its utopianism into the missile defense issue,” Westwick writes. Their impatience—they wanted giant space stations now—was similar to the attitude that infused SDI: skipping straight past traditional ground-based intercept missiles directly to a space-based system.

As Westwick explains, “there is no contemporary evidence that [the Council] played a direct policy role in the Reagan Administration’s shift from strategic deterrence to defense. The actual seeds for SDI came rather from technological developments including directed-energy weapons, such as the X-ray laser, but far more so in micro-electronics, phased-array radars and infrared focal-plane arrays; from strategic debates over MX missile deployment and ballistic missile submarine vulnerability, and moral and political concerns about the nuclear arms race, including the Freeze movement and the Catholic bishop’s letter on nuclear weapons.” Many different factors, technological, political, and even moral, led to a search for a radical break from the existing Cold War paradigm of Mutual Assured Destruction.

Westwick does believe that some of the factors that led to SDI resulted from the pro-space development movement: “The L5 Society and space enthusiasts in general, however, were among the groups that prepared the ground for SDI through public arguments for space-based missile defense. And the L5 Society was one of the first, starting with Keith Henson’s article of 1976, and prominent L5 members became important SDI advocates, in particular Lowell Wood, who made the X-ray laser a centerpiece of the public debate over SDI.”

There were also direct connections as well: when retired General Daniel Graham created the High Frontier organization in 1981 to lobby for missile defense, he hired some of his staff from the L5 Society. They had political action experience and mailing lists. Jerry Pournelle wrote that “Dan Graham essentially took the remains of the L5 Society and built his High Frontier out of it.”

Some of the connections between the space settlement movement and Reagan’s SDI also appear to go beyond mere coincidence. J. Peter Vajk’s 1978 book on space settlement, Doomsday Has Been Canceled, stated that space-based lasers “would render ICBMs totally obsolete.” Science fiction author Gregory Benford wrote a 1981 article for Omni magazine titled “Zeus in Orbit” with the subtitle “Particle-beam weapons threaten to scuttle ballistic missiles and make the MX obsolete.” Reagan’s March 1983 speech called for the scientific community to “give us the means of rendering these weapons impotent and obsolete.” Even if these authors did not directly copy each other, clearly they were borrowing from a common lexicon.

The Star Wars legacy

Westwick claims that SDI and missile defense had a lasting influence on American space policy. Reusable launch vehicles, inflatable spacecraft, and infrared astronomy did not originate as ideas in the SDI program, but they certainly gained momentum from it. One question worth evaluating that is beyond the scope of Westwick’s article is the actual legacy, both technological and political, of the Strategic Defense Initiative. The Strategic Defense Initiative Organization spent $26 billion over ten years and launched over a dozen spacecraft into orbit, some of them with sophisticated sensors on board. What was the result of all this effort? Did it improve sensor technology that benefited military and civilian operations in the 1990s and later? How much money was spent on dead-end projects? How can we measure or even identify spin-off technologies? A 1994 Lawrence Livermore paper titled “Legacy of the X-Ray Laser Program” credits the project with numerous technology developments that seem a bit dubious. Unfortunately, there has not been any detailed historical exploration of SDI’s development of improved infrared sensors—which received substantial research funding—and their possible role in astronomy.

One of Westwick’s intriguing observations is that the 1970s represented a time of change in how American politics, and its ideological factions, engaged with technology. Liberals who had embraced John F. Kennedy’s frontier imagery and concepts of technological progress in the 1960s began to turn away from them by the 1970s. “Some liberal commentators for their part came to view the frontier myth as an emblem of imperial conquest, environmental damage, selective government subsidies and corporate profiteering,” Westwick writes. (Although he does not note it, space colonization advocates eventually abandoned the loaded term “colonization” in favor of the far more neutral “settlement”; see “Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true?” The Space Review, May 1, 2017.) Conservatives, who had long been skeptical of “Enlightenment faith in progress and improvability of humankind, became technological enthusiasts,” Westwick claims. But the 1970s were also a time “when far-out ideas—asteroid mining, biofeedback or space-based missile defense—could receive a hearing at either end of the political spectrum. It also demonstrates how the far left and far right could, like a closed universe, bend around and meet at particular points.”

| But the 1970s were also a time “when far-out ideas—asteroid mining, biofeedback or space-based missile defense—could receive a hearing at either end of the political spectrum. It also demonstrates how the far left and far right could, like a closed universe, bend around and meet at particular points.” |

Westwick notes that the L5 Society embraced a kind of secular religion that had humanity ascending, but “when L5 enthusiasts talked about rising up to reside in the heavens, they meant it literally.” That religion spread and morphed in unusual ways. But there was also another side to it: what the Soviet Union might be doing. The L5 News provided its members with the latest information on Soviet space efforts, and somewhat approvingly noted with envy that “scientific bigthink is a fully approved literary genre in the Soviet Union.” Writers like Jim Oberg predicted that the Soviets might have the first space colonies by 2000.

The world has turned out a lot differently than the doomsayers and the visionaries of the 1970s and 1980s predicted. We never experienced the mass famines, resource scarcity, and societal collapse predicted by The Club of Rome. We also found a peaceful way out of the Cold War, leaving behind the threat of global thermonuclear war. But achieving the vision of thousands of people living and working in space remains as elusive today as it did four decades ago.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.