Beyond UNISPACE: It’s time for the Moon Treatyby Dennis C. O’Brien

|

| Space commerce is taking off, both literally and figuratively, and the laws of outer space need to keep up. |

That decision, and the underlying political philosophy, were wrong. Forty years later, experience has shown us that, if an activity in space is commercially viable, private industry should be allowed and even encouraged to do it. Not only does such a policy free up the creativity, talent, and resources of free enterprise, it also allows governments to concentrate on exploration and other missions that serve public policy interests.

The Moon Treaty acknowledges a role for private enterprise as “non-governmental” entities. Although it requires all private activities in space to be under the “supervision and control” of their country of origin, it does not specify any further regulations. Rather, it leaves it up to the “Member States”—those nations who have adopted the treaty—to create a framework of laws to facilitate the “safe and orderly” commercial use of space resources, at such time when such regulations become necessary:

Bearing in mind the benefits which may be derived from the exploitation of the natural resources of the moon and other celestial bodies… (Moon Treaty, Preamble)

States Parties to this Agreement hereby undertake to establish an international regime, including appropriate procedures, to govern the exploitation of the natural resources of the moon as such exploitation is about to become feasible. (Article 11.5)

The main purposes of the international regime to be established shall include:

(a) The orderly and safe development of the natural resources of the moon;

(b) The rational management of those resources;

(c) The expansion of opportunities in the use of those resources;

(d) An equitable sharing by all States Parties in the benefits derived from those resources… (Article 11.7) [4]

It is worth repeating that the Moon Treaty does not mandate any specific regulation for space commerce, but does require countries to create such regulations as the need arises. It now appears that the need has arisen, as evidenced by two general trends. One is the explosion of commercial space startups, many of which are targeting the Moon and other space resources. The other is the heightened focus by national and international organizations on the issue of space governance. Some countries have passed their own national laws concerning space commerce, while more international conferences are putting space law on their agendas or even devoting entire conferences to it. Space commerce is taking off, both literally and figuratively, and the laws of outer space need to keep up.

The concerns of private enterprise and others

Article 11 of the Moon Treaty requires and empowers the Member States to create an international framework of laws (“regime”) to regulate space commerce. As with all such regulatory efforts, private enterprise has serious concerns which can be summarized as follows:

- Inadequate or nonexistent private property rights (space as the “common heritage of mankind”);

- An “enterprise”, i.e. a government-owned corporation that would exploit space resources (similar to the one detailed in the Law of the Sea treaty);

- Lack of protection for intellectual property;

- Regulations that would burden free enterprise with public policy concerns:

- Possible payment of fees, royalties, and/or taxes.

- An inadequate decision-making process for determining future regulations, procedures, and funding.

Three additional concerns have been raised by other non-governmental organizations and private individuals:

- A lack of provisions for establishing settlements on the Moon and other celestial bodies;

- An apparent ban on terraforming;

- Lack of protection for individual rights.

Every one of these concerns can be addressed by a proper interpretation of the Moon Treaty through the use of an Implementation Agreement (IA), as was done with the Convention on the Law of the Sea in the 1990s.

The Law of the Sea and the use of an implementation agreement

At this point it will be helpful to review how the use of an implementation agreement revived a similar effort to establish another international framework of laws, the Law of the Sea.

Many critics have compared the Moon Treaty with the United Nations’ Convention on the Law of the Sea (CLOS), claiming that the latter is a failed treaty that has prevented the development of undersea resources and fearing that the former would do likewise. They are especially critical of the creation of an “enterprise,” a government-owned entity that would use the development of undersea resources to assist countries that were adversely affected by undersea development.

If the international regime envisioned by the Moon Treaty takes a form similar to that of the Enterprise, developed nations would be required to relinquish a portion of the resources extracted from the Moon and other celestial bodies. [5]

Such concerns were very reasonable in the 1980s. At that time, many were insistent that governments should own and operate large industries rather relying on capitalism and private enterprise. Even the United States was requiring almost all satellites to be launched on the government-owned shuttle.

| If a company believes it can make money from an activity in space, it should be permitted to make the attempt, so long as other public policy concerns are satisfied. |

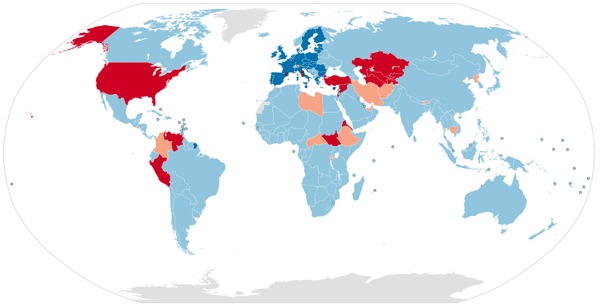

All of that has changed, beginning with the Challenger accident in 1986. By 1991 the Soviet Union had ceased to exist and there was no longer a Cold War battle between capitalist and communist philosophies. The United Nations increased its efforts to broaden support for the CLOS, resulting in the Implementation Agreement (IA) in the early 1990s. The CLOS and its IA came into effect in 1994, one year after Guyana became the 60th country to adopt it. It has now been adopted by 157 countries (see map below). Even the United States almost adopted it. The CLOS had received bipartisan support in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, but in 2012 34 senators signed a letter saying they would not vote for it, denying it the two-thirds majority needed for ratification. [6]

There are now 29 entities who have signed contracts with the newly-created International Seabed Authority for exploration and possible development of seabed resources. [7] A treaty that was once thought dead was given new life through the use of an implementation agreement to address unresolved concerns.

Fig. 1. Map of countries (in light/dark blue) that have adopted the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea. [8] |

The strategy of using of an additional document to make the five space treaties more universal gained support in the COPUOS legal subcommittee at their June conference:

13. The view was expressed that the universality of the five United Nations treaties on outer space should be strongly supported and promoted, and that effective implementation of the treaties required broad adherence due to the increasing number of parties holding a stake in outer space activities.

14. Some delegations expressed the view that the guidance document envisioned under thematic priority 2 of UNISPACE+50 (Legal regime of outer space and global governance: current and future perspectives) and developed within the Working Group on the Status and Application of the Five United Nations Treaties on Outer Space, could offer valuable guidance to States wishing to become a party to the five United Nations treaties on outer space and could thus help to promote the universality of those treaties, greater adherence to them and the progressive development of international space law. (emphasis added) [9]

The Implementation Agreement for the Moon Treaty can be that guidance document. Of course, the devil is in the details. But there can also be many angels there that address the concerns of all stakeholders while maintaining a process that promotes public policy principles. A review of the nine concerns through the filter of a potential Implementation Agreement will reveal some of those angels.

Concern: Commercial property rights

Article 11.3 of the Moon Treaty states:

Neither the surface nor the subsurface of the moon, nor any part thereof or natural resources in place, shall become property of any State, international intergovernmental or non- governmental organization, national organization or non-governmental entity or of any natural person. [5]

But Article 11 also implicitly recognizes the existence or creation of personal property rights by authorizing laws to govern the commercial use and exploitation of space resources. Without such rights there would be no commerce and no need for an international “regime” of laws. This interpretation is bolstered by the qualifier “natural resources in place” in 11.3 above. Once resources are no longer in situ, they become the personal property of whatever entity or person that removed them. [10]

Of course, this begs the question of how someone gets permission to remove the “natural resources in place”. That would be the role of the agency or authority that administers the international framework of laws concerning the “orderly and safe development of the natural resources” that is mandated by Article 11.7. Such authorizations could be in the form of “priority rights,” as recently proposed by The Hague Space Resources Governance Working Group:

6. Access to space resources

6.1 The international framework should enable the unrestricted search for space resources.

6.2 The international framework should enable the attribution of priority rights to an operator to search and/or recover space resources in situ for a maximum period of time and a maximum area upon registration in an international registry, and provide for the international recognition of such priority rights. The attribution, duration and the area of the priority right should be determined on the basis of the specific circumstances of a proposed space resource activity. (emphasis added) [11]

An Implementation Agreement for the Moon Treaty should confirm that the implementing authority can grant such priority rights to those engaging in space commerce.

Concern: A government-owned “enterprise”

The Convention on the Law of the Sea originally called for an “enterprise” that would be owned by the international authority. It would have operated like a private company, with proceeds being distributed to less-developed countries. It relied on the declaration that ocean resources were the “common heritage of mankind.” Although the Moon Treaty does not expressly describe such an enterprise, it likewise declares that outer space is the “common heritage of mankind” and implies that there will be some agency or authority to administer the international framework of laws that the treaty requires. Many have concluded that the treaty thus envisions a government-run “enterprise” for outer space and have criticized it for doing so.

| Rather than viewing such obligations as burdens, commercial interests should embrace them as a way to fulfill their overall obligation to share the benefits of space commerce with all countries. |

But it is not necessary to establish such an enterprise to implement the Moon Treaty. If a company believes it can make money from an activity in space, it should be permitted to make the attempt, so long as other public policy concerns are satisfied. That statement of policy should be part of the Implementation Agreement, along with the declaration that creating a government-owned “enterprise” will not be within the portfolio of any agency that administers the international framework of laws.

Concern: Status of intellectual property rights

The Moon Treaty’s use of the “common heritage of mankind” has also raised concerns about the status of intellectual property rights.

They [developed countries] would also be required to surrender technology developed by private industries under their jurisdiction for extracting extraterrestrial resources so that developing nations could participate in the activity of acquiring those resources as well. This implies that the Moon Treaty’s common heritage view applies not only to extraterrestrial real property and resources but to intellectual property rights as well. [5]

This concern can also be addressed by the Implementation Agreement for the Moon Treaty, based on the language in the IA for the CLOS:

Section 5: Transfer of Technology

(a) The Enterprise, and developing States wishing to obtain deep seabed mining technology, shall seek to obtain such technology on fair and reasonable commercial terms and conditions on the open market, or through joint-venture arrangements;

(b) …States Parties undertake to cooperate fully and effectively with the Authority for this purpose and to ensure that contractors sponsored by them also cooperate fully with the Authority;

(c) As a general rule, States Parties shall promote international technical and scientific cooperation with regard to activities in the Area either between the parties concerned or by developing training, technical assistance and scientific cooperation programmes… [12]

Although such a provision would require private companies to share technology, it would also mandate that they are paid a fair and reasonable amount for its use. An exception would need to be made to the “general rule” for technologies that have been barred from export for national security reasons. The provision would thus protect private economic interests and national security interests while ensuring that less-developed nations have the technical capacity to share in the development of space resources.

Concern: Public policy regulations

Those who engage in free enterprise would like to be free from all government regulation. They argue that society would be best served if everyone acted in their own enlightened self-interest. The “invisible hand” of distributive economics, as popularized by Adam Smith, would be all the guidance that was needed. Those who make business decisions will do so in the public interest because what’s good for the public is good for business.

There are few metaphors that have captured the American economic psyche as powerfully as the “invisible hand” of the market. The term, first coined by Adam Smith in 1759, is used to describe how the self-interested behavior of people in a marketplace leads to the greater good for all. No need to rely on concerted efforts of government or the church to direct commercial activity. If the proper economic and legal institutions are set up, we can all be made better if simply left to our own devices. [13]

Alas, this theory does not work in practice. A prime example is the ever-growing amount of space debris in low Earth orbit. Even now satellites are being placed in orbit without systems that would deorbit them at the end of their lives. In business, the desire to save money in the short term is always stronger than long-term public policy concerns. Paying more to build a satellite with a deorbit system would put a company at a competitive disadvantage to a company that did not. That’s why laws are required to get private enterprise to attend to such concerns. In addition to serving public policy, such laws prevent any company from gaining an unfair competitive advantage over another.

| Although it is the mission of corporations to avoid costs and increase profits, it is too much to assume that there will be no cost for the exploitation of outer space resources. |

What are the public policy concerns that private enterprise would need to honor? Article 11.7 of the Moon Treaty describes the international framework of laws concerning space commerce, stating that their purpose is the orderly and safe development of the natural resources of the Moon, the rational management of those resources, the expansion of opportunities in the use of those resources, and an equitable sharing by all States Parties in the benefits derived from those resources. Any regulations established to further these public policies would need to be honored by private enterprise.

The treaty also describes several obligations concerning “national activities” that can be applied private enterprise as well as governments. Such obligations would include:

- Using space resources exclusively for peaceful purposes (Art. 3.1);

- Providing co-operation and mutual assistance (4.2);

- Informing the public of activities (5.1);

- Informing the public of “any phenomena… which could endanger human life or health, as well as of any indication of organic life” (5.3);

- Protecting the environment (7.1) (this could also include protecting historical legacies, such as early Moon landing sites);

- Reporting any significant discoveries (7.3);

- Not impeding free access to all areas by other parties (9.2);

- Honoring the Rescue Treaty (10.1).

An Implementation Agreement for the Moon Treaty would specify the extent to which the obligations of Member States would also apply to private enterprise. As it currently stands, the Treaty appears to apply such obligations to all “national” activities, which would include private enterprise. This interpretation is bolstered by a bill passed last year by the House of Representatives that seeks to unilaterally exempt nongovernmental entities (NGOs) from such obligations. [14]

Rather than viewing such obligations as burdens, commercial interests should embrace them as a way to fulfill their overall obligation to share the benefits of space commerce with all countries. To the extent that they require the sharing of “proprietary” information, like the discovery of a mineral deposit, they might even be a deductible expense under a company’s national tax laws. Indeed, all money spent meeting public policy obligations would be considered a necessary business expense, whereas without the legal obligation to do so they might not be.

Concern: Assessment of fees, royalties, or taxes

Although the assessment of payment for use or exploitation of space resources is not specified in the Moon Treaty, the declaration that such resources are the “common heritage of mankind” (CHM) implies the authority of any implementing agency to do so. Such is the case with the Convention on the Law of the Sea, which also uses the CHM concept. In the CLOS, governments, NGOs, or individuals can contract with the international authority to explore certain areas of the seabed and exploit the resources found there. The fees that they pay are used to support the administrative work of the agency.

The Authority shall have its own budget. Until the end of the year following the year during which this Agreement enters into force, the administrative expenses of the Authority shall be met through the budget of the United Nations. Thereafter, the administrative expenses of the Authority shall be met by assessed contributions of its members, including any members on a provisional basis,… until the Authority has sufficient funds from other sources to meet those expenses. - Agreement Relating to the Implementation of Part XI Of The Convention [on the Law of the Sea], Section 1.14 [12]

This arrangement was set forth in the Implementation Agreement that was worked out for the CLOS, just as it can be included in an IA for the Moon Treaty. For those who are concerned about a bloated administrative agency [15], the CLOS IA even provides an efficiency clause that could be adopted for the Moon Treaty IA:

Annex Section 1.2: In order to minimize costs to States Parties, all organs and subsidiary bodies to be established under the Convention and this Agreement shall be cost-effective. This principle shall also apply to the frequency, duration and scheduling of meetings. [12]

The payment of fees and royalties for the use of public lands is common on Earth. Although it is the mission of corporations to avoid costs and increase profits, it is too much to assume that there will be no cost for the exploitation of outer space resources. Whether such payments would be used for purposes other than administrative costs would be up to the Member States, using their decision-making process.

Concern: Inadequate decision-making process

The above analysis and proposals only work if there is a decision-making process in place to determine regulations, potential fees, and the use of proceeds. Alas, the Moon Treaty is silent on how such a process should be structured. Once again, the Convention on the Law of the Sea and its Implementation Agreement offer a way forward.

That agreement establishes an entity separate from the United Nations, composed of an assembly made up of all member states and an executive council made up of 36 states who are chosen by the assembly. Membership on the council consists of five subgroups to assure that all interests and interested parties are served. For example, one group is made up of countries who each generate more than two percent of the world’s GDP. Although consensus is preferred, it is possible to make decisions in both the assembly and the council by a simple majority for procedural matters and by two-thirds majority for substantive matters. However, all decisions on financial matters, including the charging of any fees, the administrative budget, and the use of any income must first be made by a 15-member finance committee that is chosen by the executive council. Decisions of the finance committee must be by consensus. [12]

How would this apply to the Moon Treaty? A good example is finances. The Implementation Agreement should specify that the implementing agency has the authority to collect fees for exploration and exploitation permits that are sufficient to cover its administrative costs. It should then state that any additional collection of revenues, and how such revenues are used, will be determined by the assembly and/or executive council after recommendation by the finance committee.

This proposal would kick the can down the road when it comes to the issue of using revenues to share the benefits of space exploitation with all nations. But it would establish a process for making such decisions. Meanwhile, humanity would benefit from other types of sharing (see the section above on public policy regulations) while building confidence in the process for making more difficult decisions.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.