There is no space raceby Roger Handberg

|

| While the United States labored through a number of iterations in future directions for its human space exploration effort, China moved forward in a systematic manner. |

In the 1950s, after the launch of the first two Sputniks, the United States and the Soviet Union embarked on the great space race with its multiple firsts that culminated in the Apollo program and the Eagle landing on the lunar surface in July 1969. That success did not signal a continuation of the space race but rather its winding down to the point that, by the mid-1970s, the United States was out of space with regards to human space exploration until the Space Shuttle first flew in 1981.

Wandering in the desert

Space advocates then entered a period of great frustration as the shuttle did not match up to the excitement and anticipation of the Apollo era. Instead, the shuttle flew to orbit and went round and round. In 1989, President George H.W. Bush tried to rekindle the enthusiasm and pride of the earlier era with his Space Exploration Initiative. That noble effort disappeared in a cloud of congressional and public indifference. The odyssey of the Space Station Freedom, now the International Space Station (ISS), was a lesson in patience and false starts before it got underway in the late 1990s.

The United States spend the 2000s working on ISS completion and recovery from the second shuttle disaster in 2003. In the aftermath of that accident, there was another effort by a Bush presidency to pursue human space exploration in the Constellation program. Unfortunately, the program was underfunded while the space shuttle was put on a path to retirement. With the shuttle’s impending shutdown, the initial choice was to close down the ISS soon thereafter, but that decision was reversed under pressure from the international partners who had committed comparatively large parts of the space budgets to the station only to see it close soon after completion in 2011.

President Obama sought a more measured approach to human space exploration with the goal of moving out into the solar system in stages beginning with a trip to an asteroid, although later the asteroid was to be moved closer to Earth. There was not a return to the Moon despite its proximity and prior visits. Mars appeared even more distant while the near-Earth problem of reaching the ISS was farmed out to the Russians, who were fine with doing so for the cash. Meanwhile NASA contracted with several private companies to develop and operate launch systems and vehicles capable of carrying first payloads and ultimately crew to the ISS. The result is that the ability to access the ISS without dependence on the Russians is close to being resolved. There have been more recently proposals to extend the ISS out to perhaps 2030 or later, but no funding decisions yet. This new termination date rejects the Trump Administration’s drop-dead date of 2025, although this assumes the ISS partners still support the extension. Some may wish to end their contribution to the ISS so that they can move on to other projects for which funding would not be available if the ISS persists.

For the United States, human space exploration in terms of moving beyond low Earth orbit has been delegated to the Space Launch System (SLS) and the Orion spacecraft. The destination has changed several times but now appears to be Moon first, and then Mars at some indefinite point in the future. How soon appears to reflect political rhetoric at different points in time: whether sooner or later depends on the speaker. The reality, though, is that there will not be an Apollo-type infusion of funding into the program, which is why the administration capped ISS funding at 2025 in order to free up funding for the Moon missions. This approach mirrors the earlier Constellation program, whose funding assumed that the space shuttle and ISS would be closed and their funding transferred to the new endeavor.

| Today, there is considerable concern about China economically, but that has not appeared to have bled over into concern about a space race. |

New goals have been set for when Americans will return to the lunar surface for—hopefully—permanent residence. All this depends on technological developments and funding, the latter never being assured from fiscal year to fiscal year. The intention is to do great things, but the fiscal commitments may turn that into a lengthy affair unlike Apollo, which went from announcement in 1961 to landing in 1969. Constellation was announced in 2004, followed in 2010 by the Obama-modified approach moving into deep space first to an asteroid. President Trump in 2017 changed direction again, back to the Moon first.

While the United States labored through a number of iterations in future directions for its human space exploration effort, China moved forward in a systematic manner, launching humans—or taikonauts—to space in its Shenzhou spacecraft starting in 2003. After several missions, China launched a small space station, Tiangong-1, in 2011. The space station was visited by two crews of taikonauts and returned to Earth in 2018 in an uncontrolled reentry.

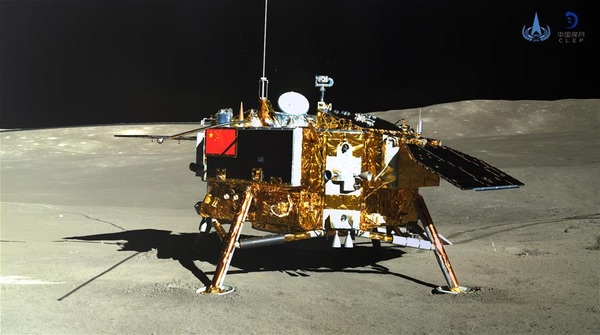

At the same time, China sent landers and rovers to the lunar surface, the most recent being Chang'e-4, landing on the far side of the Moon this month. For China, this was a “space first” in that no other spacefaring nation had landed on the far side before. For the event to occur, China had to also launch a communications satellite so that the Chang’e-4 could communicate back to Earth. China is also developing a space station to be assembled in orbit, completed by 2022.

Why is this important?

China’s space feats come at a time when China is aggressively asserting its status as a great power after what they perceive as a century of humiliation. This assertiveness has taken many forms, and many within the space community believe that China’s rise, almost by definition, should rekindle a space race between the United States and China. The operative assumption is that the US cannot fail to respond to this challenge by carrying out a more ambitious space program. This further is exacerbated by China’s statements that it wishes to conduct future missions at the Moon and elsewhere in cooperation with other nations. China has already made gestures toward cooperative missions with the Europeans and other countries, such as its long-standing alliance with Brazil. The US Congress has restricted NASA from cooperating with China without prior congressional approval, due in part to technology transfer concerns.

In an earlier generation, the shout “The Russians are coming,” was sufficiently present in American culture that a comedy film took that title. Today, there is considerable concern about China economically, but that has not appeared to have bled over into concern about a space race. Efforts by former Rep. Frank Wolf (R-VA) to foster public fear of China in the context of a space race did not gain much traction (see “China, competition, and cooperation”, The Space Review, April 10, 2006). That does not mean that China does not measure its accomplishments in terms of the United States, which is what makes the farside lunar landing so critical since the US and the Russians have not been there yet. That is an important marker of China’s accomplishments, but its importance to the Americans is less critical.

| The crowds come to see SpaceX and others launch from the Cape, not NASA. NASA will pursue human space exploration but in a manner reflective of its relative importance in American politics. |

Both the United States and China compete, but at a different level of intensity than occurred in the early days of the space age. NASA, when it was charged with the lunar landing challenge, went on a virtual wartime footing because time was of the essence. Competition still occurs now but at a far lower intensity, as shown by the budget share of NASA compared to the frantic early days of the space race. For space advocates, there is a lingering belief that the golden era of the Apollo program can be recaptured, but the death of the SEI by neglect should have killed that myth. The end of shuttle flights was truly the end of the space future as envisioned by Werhner von Braun and the original space pioneers who flew to the Moon.

The American space effort is being expanded in dramatic ways as commercial space reality moves closer to the dreams of the space believers. NewSpace draws public attention because it is now more in the public light than NASA. The crowds come to see SpaceX and others launch from the Cape, not NASA. NASA will pursue human space exploration but in a manner reflective of its relative importance in American politics. Members of Congress (in selected districts) may lose office over a failure to adequately support NASA but no presidential candidate has lost an election over falling behind in a space race. That is the reality: the Chinese race alone, while the Americans push their way forward more slowly. Others, like India, aspire to join the human space exploration endeavor, but that will come more slowly. Shortcuts lead to failure, and one has to build the necessary technological and human resources base for long-term success in exploring outer space.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.