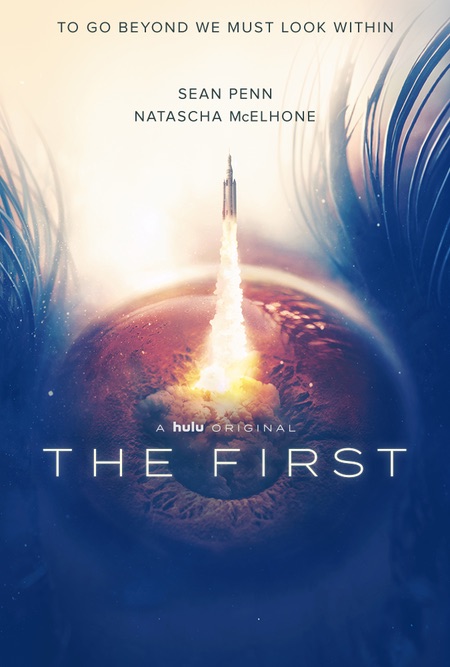

The First didn’t lastby Jeff Foust

|

| That fanfare, though, ultimately did not translate into fans. |

The series starts, as one might expect with a show about a mission to Mars, with the launch of that first expedition, Providence 1, on a rocket that looks like a Block 1 version of the Space Launch System with an Orion spacecraft on top. All well and good—until the rocket explodes a couple minutes after liftoff, killing its five-person crew. (Why the Orion’s launch abort system didn’t save the crew isn’t clear.)

Penn’s character, Tom Hagerty, is an astronaut who was supposed to command that mission, but was removed from the crew after the death of his wife and estrangement with his daughter, a young woman battling drug addiction. He is swept back into the program after the accident, helping convince reluctant members of Congress, and the president, to back a second mission. He wins command of that second mission, even as he seeks a rapprochement with his daughter.

The eight episodes trace the two-plus years of preparation for that second mission. It follows the lives of the other crewmembers and Laz Ingram (Natascha McElhone), the head of Vista, the company responsible for the program. Vista’s relationship with NASA isn’t described well in the show: it, rather than NASA, seems to be running the program, yet is dependent on federal funding for it to continue. In the promotion for the series, Ingram was described as a driven entrepreneur—a female Elon Musk, perhaps, with a reporter in one episode even asking her if she was “on the spectrum”—but in the series she more often appears like an executive of a conventional aerospace company, one who desired to carry out that Mars mission, but also to keep those government dollars coming in.

The other members of the Providence 2 crew don’t get nearly as much attention as Hagerty. Kayla Price (LisaGay Hamilton) was set to command the mission, but doesn’t seem to show any animosity about losing that command, happy to serve as effectively second-in-command instead. We only get modest insights into her life as well as the other crew: a scientist in a troubled marriage, an engineer with both young children and a mother suffering from dementia, a doctor with a war injury that threatens his place on the mission, and a pilot whose character is never described any detail. By comparison, one episode—of eight—was devoted almost entirely to flashbacks describing Hagerty’s relationship with his daughter and late wife.

There was another thing missing from the series as well: Mars. The Red Planet was literally and figuratively hundreds of millions of kilometers away during the episodes, set largely in New Orleans. (Why the show is there isn’t explained; while elements of rockets like the SLS are built in the city at the Michoud Assembly Facility, astronauts don’t live, work, and train there, and rockets aren’t launched from there, but all of that takes place in the series.) There is a subplot over a few episodes involving a problem with the Mars ascent vehicle (MAV) already on the surface that the crew will use for the trip home. But the problem gets stretched out over those episodes (covering many months) and, when the solution doesn’t work, they simply press ahead, relying on the MAV that will be going to Mars with the new mission.

The First emphasized character drama over science fiction in its eight episodes, but moved too slowly for many. (credit: Hulu) |

In The First, Mars is overshadowed by the human drama of going there. That would be great, if the drama worked. But the plot is slow, and focused primarily on Hagerty and his family, and to a somewhat lesser extent Ingram. There’s not a lot of interpersonal conflict among the members of the crew, who generally seem to get along pretty well, even when the addition of Hagerty forces them to take the scientist off the crew: she stays involved, even as she’s forced to train the pilot to handle the work she would have done. When the doctor’s war injury, affecting his hearing, flares up, one expects him to try and hide it to stay on the crew and be one of the first to walk on Mars. Instead, he’s upfront about it, and accepts being taken off the crew, allowing the scientist to return to the mission. It’s the professional attitude one would expect from astronauts, but it dampens the drama.

| Perhaps the show is a sign that the idea of going to Mars is embedded enough in society that it can be the basis for a dramatic series without it being so much about Mars itself. |

And the series, ultimately, doesn’t deliver on the drama. There’s no physical risk to the crew, since they’re still on the ground training, and the political risks, particularly in the early episodes, never seem that significant. The problem with the MAV was supposed to present a technical risk to the mission, but when engineers couldn’t resolve it, they went ahead with the mission anyway, accepting higher odds that they might not be able to make it back. The season’s final episode is less a dramatic climax then a denouement: Providence 2 launches without incident and leaves Earth orbit, bound for Mars. Roll credits. It’s hard to get too invested in a series when the outcome seems inevitable.

Prior to the debut of the series, Mars advocates saw The First as another sign of public interest in real Mars exploration, alongside the hit movie The Martian and the series Mars on the National Geographic Channel (see “Mars: Bringer of ennui” part 1 and part 2, January 21 and 28, 2019). Last May’s Humans to Mars Summit in Washington featured a panel about the then-upcoming show that included Willimon and Hamilton as well as former astronaut Michael Lopez-Alegria, who served as a consultant to the show. (The same conference previously promoted the NatGeo series as well.) But the series was unlikely to generate more enthusiasm about Mars exploration, even if it had found its audience.

Although the Louisiana setting for the show doesn’t seem credible, the producers did take steps to make the series technically realistic otherwise, like the use of the SLS and Orion and a modular spacecraft for traveling to Mars. (Had the series continued to an actual landing on Mars, it would have been interesting to see what approaches they would have used there.) The use of ersatz NASA logos suggests the producers either could not obtain, or did not seek, permission from the agency to use them, or other guidance it. The show is set in the 2030s, a decade often cited as a goal for the first human missions, but also close enough to the present that the show didn’t have to make radical changes to technology or culture: people dress pretty much the same as they do now, although smartphones appear to have been replaced with earbuds, smartwatches, and Google Glass-like eyeglasses (iGlasses?).

Mars exploration advocates have long been looking for a movie or television series that would stimulate demand for human missions to Mars. That hasn’t been the case, even with the success of The Martian: after all, in the last couple years the pendulum has swung back to the Moon as a destination for human spaceflight. Perhaps, though, the show is a sign that the idea of going to Mars is embedded enough in society that it can be the basis for a dramatic series without it being so much about Mars itself. It just needs to remember to be dramatic.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.